Good sleep is critical and improving sleep has massive benefits. Given this, I find it worth the effort to experiment with tools, behaviors, devices, and molecules to optimize it.

I discuss non-pharmacological sleep optimization in more detail here.

Some of my friends use “natural” molecules to help them fall asleep faster. These include alcohol, passionflower, valerian root, phenibut, and weed. I prefer low doses of prescription drugs.

Of course, relying on exogenous molecules, whether “natural” or not, to induce or maintain sleep is suboptimal – but so is sleeping suboptimally. If lifestyle interventions do not cut it, I weigh the risks and downsides of taking a sleeping pill against the risks and downsides of shitty sleep.

Furthermore, sometimes I have caffeine or other modafinil in my system. These molecules artificially impair sleep quality. In my opinion functionally “counter-regulating” is not more artificial than having these molecules in my system in the first place.

Melatonin & melatonin-receptor agonists

According to the available data, low doses of melatonin or melatonin receptor agonists are quite safe. However, while they help with sleep onset, for most people, they help little with sleep maintenance.

Given that melatonin is a hormone that regulates seasonality (including hibernation) in vertebrates, in larger doses, it can cause hormone imbalances.

Melatonin

In the past, I have been taking low doses of melatonin for extended periods of time. Melatonin is a hormone with a variety of different effects. Melatonin drops core body temperature, entrains circadian rhythm, helps with sleep onset and quality, and amplifies growth hormone release during sleep.

In many vertebrates, melatonin also controls seasonality and hibernation and as part of the “winter program” downregulates some of the hypothalamic hormones, such as thyroid hormones, cortisol, or sex hormones. Because of this, I only ever used it at low doses (0.3-0.5mg), and I would consider any more than that “abuse”.

I currently do not use it because, for me, the risks and downsides, especially concerning the endocrine system, outweigh the benefits. However, some of my friends use it (usually 0.3-0.5mg taken 30 minutes before bed) and some derive a lot of benefits from its use. For me personally, the only use of melatonin is for counteracting jet lag.

Small physiological doses of melatonin are particularly useful for older individuals, who are often melatonin deficient.

Sublingual administration is particularly helpful for sleep onset, though it may result in an unnaturally steep spike in melatonin plasma levels. However, sublingual administration may more than double bioavailability and may therefore require an adequate dose reduction.

Ramelteon

Ramelteon is a melatonin receptor agonist. The half-life is much longer than that of melatonin. I have never tried it, so I cannot comment on its effectiveness.

Agomelatine

Agomelatine is classified as an antidepressant. It not only acts on melatonin receptors but also blocks 5HT2C receptors, resulting in an increase in dopamine levels in the prefrontal cortices, among other things. A friend has tried it with okay results.

Z-drugs

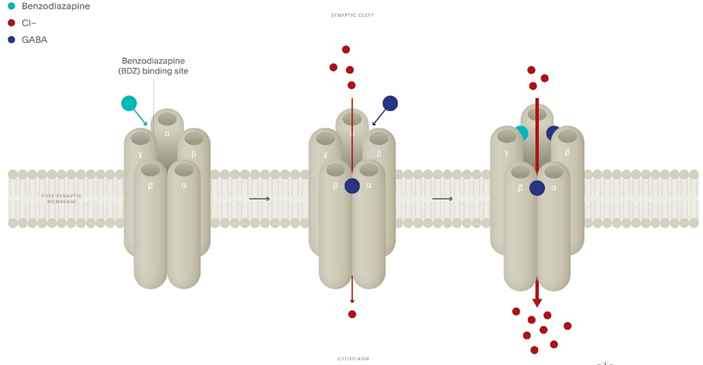

GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter. GABA causes neuronal inhibition, basically turning down the volume of everything. If GABA is potentiated, wakefulness decreases and so does anxiety, motivation, attention, cognitive function, and most other things animals use brains for. GABA is discussed in more detail in An Introduction to Neurotransmitters.

Z-drugs, like benzodiazepines, are molecules that allosterically modulate the GABA-A receptor. Positive allosteric modulation is a type of regulation in which a molecule (called the allosteric modulator) increases the activity of a protein (called the target protein) by binding to a specific site (called the allosteric site) other than the protein’s active site.

In other words, Z-drugs (like benzodiazepines) amplify the activity of the GABA-A receptor, increasing GABAergic tone. Z-drugs bind to the same binding site as benzodiazepines (discussed next) but are chemically distinct.

Even though all Z-drugs should in theory have very similar effects, there are several differences, in part due to the receptor subtypes Z-drugs bind to.

Z-drugs (zolpidem and zaleplon more so than zopiclone) bind selectively to a subtype of the benzodiazepine receptor, the alpha 1 isoform, which is thought to favor hypnotic effects over other GABAergic effects.

Zolpidem

Millions of people around the world rely on zolpidem (Ambien) for sleep, partly because it is cheap as dirt and partly because it has been hyped to be relatively free of adverse effects. Only one of these is true.

No matter at what dosage I tried it, my experience with it was always crap. For me, it did not “enhance” sleep quality, it only “knocked me out”. My Oura ring did not like it either. Even at very low doses (1-2mg), my slow-wave-sleep suffered. Furthermore, every time I took it, I had quite vivid dreams, and sometimes nightmares, which I rarely have otherwise.

After taking Ambien, a friend discovered through his browser history that he had been on Reddit the entire night but he had no memory of it. Unsurprisingly, there are several lawsuits against the manufacturer because of its relation to parasomnias (weird sleep behaviors), including sexual assault and murder.

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

Zopiclone

In the past, I have taken low doses of zopiclone (1mg) for an extended period of time. To me, it felt vastly different than zolpidem (a Z-drug) but quite like a short-acting benzodiazepine.

I started taking it during a time I had a tough time staying asleep. Zopiclone worked like a charm. Subjectively, it produced a restful sleep with no hangover. Throughout my time taking it, my Oura consistently showed great numbers in both the REM as well as the SWS department.

Unfortunately, life kept going and I never weaned off due to fear of rebound insomnia (which I then could not afford to have). At the time, I thought that there were not any issues with taking something to “hack” my sleep and the improvement in sleep quality probably outweighed the associated risks anyway. However, I was very likely wrong.

I ended up taking a low dose of eszopiclone (1mg) for over a year.

One day, and against conventional advice to taper, I simply stopped taking it cold turkey. That night I woke up at 5 am and could not go back to sleep. That was it. Interestingly, other than that I did not have any withdrawal symptoms whatsoever, and my sleep latency and sleep quality remained unchanged.

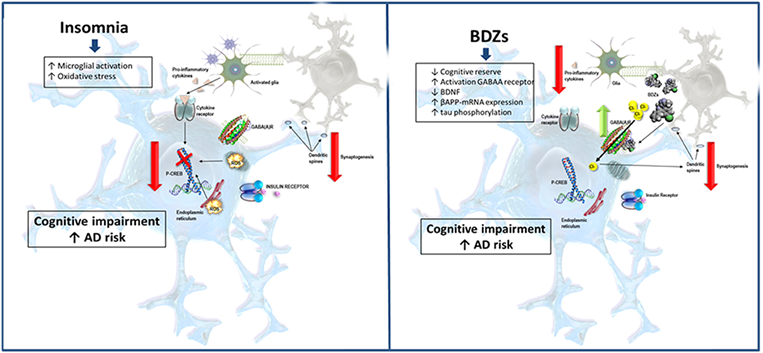

In sum, I may have derived some benefits for a short period of time. However, overall, I likely did more harm than good. Obviously, I felt stupid for having been on a sleeping pill for much longer than “necessary”. Taking sleeping pills when I do not really need them is a stupid thing to do. The association between GABAergics (e.g., benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, gabapentinoids) and dementia is quite robust and seems to be not fully explainable by residual confounding.

A friend of mine benefitted for about a month from it before he developed seemingly complete tolerance to its sleep-promoting effects. However, he continued to suffer from memory issues for the time he kept taking it. He simply stopped taking it, and just like me, he did not have any noticeable withdrawal.

In summary and in my opinion, zopiclone is okay for occasional use, but long-term use carries probably more risks (particularly cognitive impairment) and side effects (e.g., amnesia) than benefits.

I still use it very occasionally before an important day, as, for me, taking it basically “guarantees” a great sleep with no hangover.

Benzodiazepines

Like Z-drugs, benzodiazepines allosterically modulate the GABA-A receptor (as discussed in the previous section).

Regular benzodiazepine use is associated with tolerance, strong counterregulation, long-lasting alterations in GABA receptors, a horrific (and neurotoxic) withdrawal, short-term cognitive dysfunction, and most worryingly long-term cognitive impairment (longer-acting drugs more than shorter-acting drugs).

Interestingly, regular usage of BDZs for sleep is associated with cognitive decline even though they seem to improve certain aspects of sleep – which should do the opposite. Short courses of benzodiazepines, or very occasional use (e.g., once or twice per week), whether for anxiety or sleep, do not seem to be associated with the risks associated with prolonged daily use.

I avoid all benzodiazepines, other than the very occasional use of triazolam, an extremely short-acting BZD with a half-life of about 2 hours.

Sometimes when I find it particularly hard to fall asleep or I wake up a couple of hours earlier than normal and cannot get back to sleep, I take ¼ of a pill of 0.25mg triazolam sublingually. For me, it works well, and because the half-life is only about two hours, there is no hangover. I do this a couple of times per month.

Gabapentinoids

Gabapentinoids such as gabapentin and pregabalin are drugs that are often used to treat epilepsy, neuropathic pain, or anxiety. Some people use them off-label to help with sleep, particularly sleep maintenance.

I have experimented with low doses of pregabalin several times at low doses (25-50mg – for reference, standard dosing for anxiety or pain is usually in a dose range of 300-900mg). I found it useful for increasing sleep duration. I got this tip from a psychiatrist, who uses it herself. Longevity doctor Peter Attia also uses 100mg of pregabalin for sleep.

Despite their different mechanism of action, gabapentinoids and benzodiazepines have remarkably similar effects and side effects, including physical and psychological dependence, addictiveness, abuse potential, paradoxical reactions, REM suppression, and suppression of cortical plasticity.

Gabapentinoids are structurally derived from GABA – hence their names (gabapentin, pregabalin, gabapentinoids). Nonetheless, even though they are structurally related to GABA and even though they are fairly similar to benzodiazepines, gabapentinoids (supposedly) leave the GABA receptors untouched.

Their effects are thought to be exclusively due to an interaction with voltage-gated calcium channels, more specifically the A2D subunit. I am a little skeptical of this and I am not sure whether this is just an ingenious marketing ploy getting doctors to prescribe them more readily. This is pure speculation, however. At least for me, gabapentinoids feel like “benzos-lite”.

Withdrawal from gabapentinoids is reportedly comparably “unpleasant” to withdrawal from benzodiazepines. Furthermore, long-term use leads to cognitive impairment and may raise the risk of dementia.

Similar to benzodiazepines, gabapentinoids are quite addictive. There is supposedly a lot of pregabalin abuse among addicts (and in prison), partly because it´s comparatively easy to get prescriptions for.

A friend of mine was completely “zombified” by using gabapentinoids for anxiety. There is also a “Lyrica survivors” Facebook group, with a lot of sad stories about how gabapentinoids anecdotally destroyed some people’s lives. I have no idea whether these stories are true, and if they are true, whether they only represent statistical outliers.

Regardless, long-term use of gabapentinoids, whether for sleep, anxiety, or pain, is likely not as benign as it is made out to be, though likely (a little?) safer than the long-term use of benzodiazepines.

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

Antihistamines

I will briefly discuss several drugs that are often used off-label for their sleep-promoting effects due to their antihistamine properties. I discuss histamine and how it relates to alertness, in more detail here: Introduction to Neurotransmitters

Diphenhydramine

Diphenhydramine (Benadryl, Dibondrin) is a potent antihistamine and anticholinergic agent. Similar to most other drugs that have an affinity for the H1 receptor, it is quite “dirty”, which, pharmacologically speaking, means that it binds to many different targets. In many countries, it is available over the counter.

The major upside compared to other antihistamines is that its half-life is only on the order of 5-7 hours. The half-lives of most other antihistamines are much longer.

I tried it once when I was 17. I felt super drowsy and “like shit” for the whole day after.

Doxepin

Doxepin is a tricyclic antidepressant with potent antihistamine properties. Like other tricyclics, it is quite “dirty”. Doxepin has an extraordinarily strong affinity to the H1 receptor but also inhibits several adrenergic, serotonergic, and muscarinic receptors.

I have never tried it. Like trazodone (discussed next), it seems to work better in older individuals for some reason. In my opinion, doxepin’s half-life, and the half-life of its metabolite nordoxepin, is too long for it to be a useful sleep drug.

Trazodone

Trazodone is an antidepressant that has been gaining traction in recent years for its sleep-promoting effects. Similar to doxepin, trazodone is quite “dirty”. It inhibits histamine receptors (H1), serotonin receptors (especially 5HT2A), and alpha-adrenergic receptors (a1 and a2).

Because of its affinity to the 5HT2A receptor, it partially blocks the effects of psychedelics. In fact, a friend of mine who is on 150mg of trazodone for his insomnia, felt very little on a hefty dose of psylocibin.

I gave it more than a fair chance, however, my personal experience has mostly been bad. For me, trazodone caused hypotension as well as an intolerable hangover-like feeling the following day. No wonder given that trazodone has a half-life of about 10h, which means that the above-mentioned receptors are occupied well into the next day. Though for a friend, who is in his fifties, it works very well.

Even though not acting directly on GABA pathways, trazodone is not to be let off the hook. Like other CNS depressants, trazodone produces cognitive impairment (especially in short-term memory) and reduces next-day levels of cortisol. Furthermore, it metabolizes into mCPP, a molecule known to produce depressogenic and anxiogenic effects.

An upside of trazodone is that it leaves sleep architecture mostly untouched. Furthermore, according to the current data available, trazodone seems a fairly safe long-term option – at least safer than GABAergics.

Mirtazapine

A friend of mine got prescribed mirtazapine as a first-line agent to help him with sleep. He has taken it one time only, as he was hungover and ravenous for the entire day after. Mirtazapine has an awfully long half-life and adverse effects on energy levels, appetite, and metabolic health.

Mirtazapine is arguably the most sedating antidepressant on the block. Its hypnotic and sedating effects are primarily due to H1 antagonism. As a rule of thumb, the greater the affinity for the H1 receptor, the greater the sedation. Likewise, H1-receptor affinity is also proportional to weight gain.

Mirtazapine is about fifty times more potent as an antihistamine than a serotonin antagonist (though few people ever call mirtazapine an “antihistamine” when referring to its antidepressant mechanism), and therefore a great sedating and fattening agent.

Because it is a potent antihistamine, it is frequently prescribed for the treatment of insomnia. In my opinion, taking mirtazapine as a sleeping pill is overkill unless someone also has a lot of anxiety.

Antidepressants are discussed in more detail here.

Quetiapine

Antipsychotics, such as low-dose quetiapine, are the go-to-sleep drugs for many psychiatrists because they are not addictive, have no abuse potential, and, more importantly, they can be combined with most other neuropharmaceuticals (and psychiatrists love polypharmacy).

The sleep-promoting effects of quetiapine largely depend on its potent antihistamine properties, which are predominant at low doses (e.g., 12.5-25mg).

One of my best friends tried a very low-dose quetiapine (12.5mg) to help him fall asleep. For him, it felt like he was bludgeoned to death, and it caused a huge hangover and killed his energy, motivation, and drive well into the next day. These side effects supposedly get better with time.

Another friend had a good experience with it. 25mg of quetiapine cured her insomnia and reduced her tendency to ruminate, which, according to her, helped her a great deal in many aspects of her life. As always, we are all different.

If taken at higher doses, quetiapine is an ultra “dirty” drug (pharmacologically speaking), blocking dopaminergic, serotonergic, histaminergic, adrenergic, and cholinergic receptors. Because antipsychotics block so many receptors, they slow down (and outright impair) proper brain function.

In the long term and at higher doses, antipsychotics cause weight gain, metabolic derangement, and increase all-cause mortality. In my opinion, quetiapine is a terrible first-line hypnotic agent (and perhaps even a terrible second-line hypnotic).

I discuss my thoughts on antipsychotics in the treatment of depression here.

Orexin receptor antagonists

Orexin receptor antagonists are the new kids on the block. Based on animal studies, orexin receptor antagonists have less propensity for causing tolerance compared to other sedatives and hypnotics. Furthermore, they do not seem to interfere with cortical housekeeping and plasticity.

On paper, they seem like the perfect sleep drugs. However, orexin antagonists are still prohibitively expensive. Insomnia treatment is a huge market, and there are currently few to no good hypnotics available. Whether orexin antagonists are as promising as they are made out to be, remains to be seen.

My current use of hypnotics

I have experimented with many hypnotics, though few have stood the test of time. Currently, I use two hypnotics occasionally:

- On days when I want to ensure a great sleep, such as before a very important meeting, I take 1mg of eszopiclone. For me, this medication virtually guarantees a restful night’s sleep with no hangover.

- On days I have a particularly challenging time falling asleep, I use a very low dose of triazolam (¼ of a pill) sublingually, which has me fall asleep shortly. I am debating whether I should switch to midazolam instead, which is less potent and has a shorter half-life.

Other experience reports

For a full list of experience reports click here.

Sources & further information

- Scientific review: Zolpidem-Associated Consequences: An Updated Literature Review With Case Reports

- Scientific review: Quetiapine Is Not A Sleeping Pill

- Scientific review: Orexin Receptor Antagonists as Emerging Treatments for Psychiatric Disorders

Disclaimer

The content available on this website is based on the author’s individual research, opinions, and personal experiences. It is intended solely for informational and entertainment purposes and does not constitute medical advice. The author does not endorse the use of supplements, pharmaceutical drugs, or hormones without the direct oversight of a qualified physician. People should never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something they have read on the internet.