A story about MDMA

It is impossible to imagine what it is like to suffer from a mental illness without having briefly touched the limits of the fragile condition we call sanity. – Sam Harris

Therefore, let’s embark on a thought experiment.

Imagine that there was a country where MDMA is legal and in a couple of days I will be taking MDMA for the first time. Let the days before this legal experience represent my baseline in terms of how I normally feel.

Judgment day arrives and I lawfully pop the pill.

After around 90 minutes or so, I am coming up. My neurobiochemistry changes and my thoughts and outlooks on life follow suit. I start to feel invincible, euphoric, and deeply grateful to be alive. Gradually, a selfless feeling of pure love for myself and others becomes the background state of my emotional experience. An upward shift in valence by many orders of magnitude from my normal baseline.

Many of my problems disappear. It is not that I do not remember them. I am quite lucid and very aware of them. However, now -full of energy, motivation, and euphoria- I view these problems through a different lens. I even see putative solutions and I am eager to tackle them in the future. The “what is” did not change, but the “how I see it” did.

Let’s fast forward 48 hours, a time when my monoamine stores have been depleted. My neurobiochemistry has changed again, but now in the opposite direction. Now I am depressed. I start to cry for seemingly no reason. I feel empty and ask: “What is the point?”

Welcome to Suicide Tuesday.

I am educated about how MDMA works, and I know exactly what is happening neurobiologically. Yet, I am carried away by the underlying emotional tone. My subjective experience is too intense, visceral, and raw. Talking myself out of my sadness by telling myself “This is biology.” is useless. Sometimes it does not matter what you know, but what you feel takes over.

The objective content of my life (the “what is”) has not changed much within this short period of time. Certainly not enough to warrant such wild swings in your state of mind.

As the biological creature I am, my emotions, thoughts, outlooks, and thinking patterns are at the mercy of my neurobiochemistry and its changes.

In each of these periods (before MDMA; during MDMA; after MDMA), my thoughts and outlooks on life are to some extent a puppet of my neurobiochemical makeup, swinging from Earth to heaven, and then from heaven to hell within just a couple of days.

Well, but isn’t all this artificial because it is substance-induced and therefore does not apply to “real life”? Let’s go with a more “natural” example.

Let’s consider patients with bipolar disorder, a mostly genetic condition where the afflicted person cycles between periods of mania (the “high”) and depression (the “low”).

While they are manic, their thoughts and outlooks on life are filled with euphoria and grandiosity. They are motivated, creative, witty, a charge of energy, they come up with projects, and they do. They think everything is possible.

Sometime later, their energy & mood cycle downward. For seemingly no reason, they are now depressed, listless, and deeply regret what they were doing only a short time ago. They are dead certain that it will never get better and that there is nothing they can do about it. They are often suicidal and a decent share of them eventually kill themselves when they are low.

Sometimes these two states are separated by only a couple of weeks, more rarely even days. In both cases, thoughts and outlooks are primarily a reflection of neurobiochemistry. (A minor version of this cycling – no pun intended – is experienced by half of the fertile human population every single month.)

But what does that have to do with me or you?

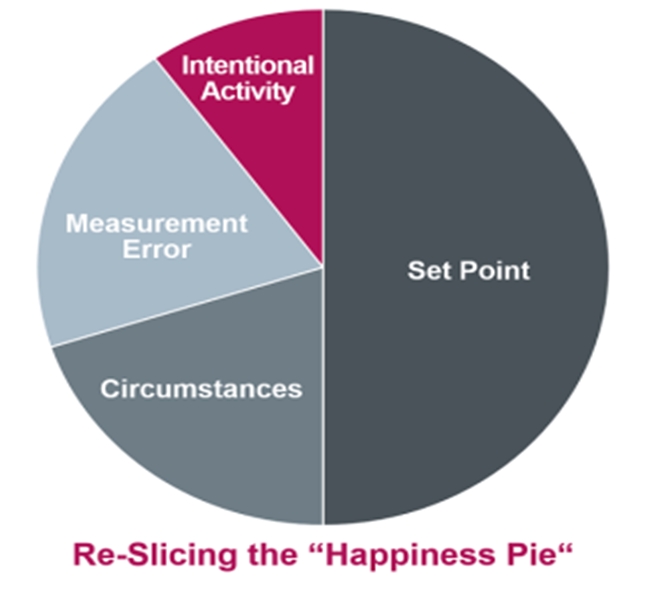

Every single one of us has a baseline level of these neurotransmitters (and other neuroplastic processes). My “setpoint” is mostly determined by genetics (over 50%), hormones, and lifestyle.

Neurobiochemistry & happiness

There is a (strong) causal link between my raw biological capacity to experience happiness and the extent to which my life is felt to be worthwhile, meaningful, and exciting. If I am depressed, I am much more likely to find life meaningless. If I feel better than well, I am much more likely to find life deeply meaningful and exciting, and I am eager to get out there and do things.

Said another way, one of the major factors determining my levels of happiness is my biology. This is not my personal opinion but is well backed up by research on monoecious twins separated at birth (to correct for any non-biological factors).

For the average human being, biological factors are as (or more) important than all of the other factors combined. However, my genes’ effect on my happiness is not by making me “happy” in the same way MDMA makes me “happy”. The effects on my happiness are much more indirect.

As mentioned in the section on guiding principles, my biological factors ripple through my life in the same way an earthquake ripples through the Earth’s crust.

Genes influence my neurobiochemistry. My neurobiochemistry then not only affects my moment-to-moment well-being (the way I “feel” on a daily basis) but also my thinking patterns, the way I act, and therefore my life overall: relationships, wealth, status, profession, lifestyle choices, etc. — which all have independent effects on my happiness levels.

My biological “set point” (including my levels of neurotransmitters as well as a number of genes and some other poorly understood biological factors) co-determines many of my personality traits, my capacity to do work, my level of motivation and drive, my thinking patterns, my general level of my (biochemical) well-being, and how my life unfolds in general.

Obviously, there are other crucial factors such as parenting style and early life experiences, but biology usually gets the short end of the stick despite probably deserving the longer end.

Very simplistically speaking, people with a great mood and boundless energy (hyperthymia) are thought to have a variety of neurotransmitters (as well as a variety of genes) set to high levels, while in depressed individuals these transmitters are thought to be quite low.

I discuss some of these neurotransmitters in more detail here: An Introduction to Neurotransmitters

The non-biological effects of antidepressants

In the same way that happiness is not just genetically determined, depression is not just a chemical imbalance.

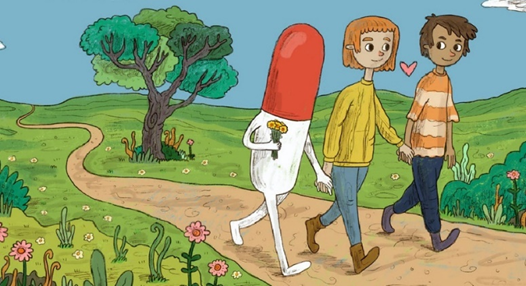

Most people consider antidepressants to be “a pill to feel well”. It is true: Antidepressants do help many people “to feel well”. However, not in the way most people think. It is also their non-biological effects that are important.

If I (lawfully) take MDMA, I will feel wonderful because its direct effects on my subjective moment-to-moment experience hit me like a truck. Antidepressants, however, work differently.

While antidepressants affect neurotransmitter function, gene regulation, neuroplasticity, neuroinflammation, and to some extent also moment-to-moment wellbeing, equally important are their non-biological effects – their indirect effects on my life circumstances.

However, it seems that these indirect effects on someone’s life situation are rarely taken into account by the scientific literature.

Let’s use the most commonly prescribed class of antidepressants as an example. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) block the transport protein responsible for the reuptake of serotonin called SERT. If this protein is blocked, serotonin accumulates in the synaptic cleft in all of the neural networks innervated by serotonergic neurons.

Let’s consider the story of imaginary Anna.

Imaginary Anna is hopeless and helpless. She is anxious and believes that things will never get better and that there is nothing she can do about it. Her doctor prescribes her an SSRI.

On the first day of taking it, she feels a little tired and weird. Without her being aware, the accumulation of serotonin works its magic in the background. Among many other things, some of the brain networks responsible for activating the fear & stress response are gradually downregulated.

Over the course of a few weeks Ana’s tendency to ruminate, stress, cry, and worry gradually abates…because the mind is what the brain does.

This automatic change to her brain metabolism is quite unlike any intentional changes Ana tried to make before she tried antidepressants. No need for any conceptual knowledge from self-help books or other strategies of to-dos and to-not-dos. She simply becomes somewhat different even if she is unaware of it.

Over the course of the first couple of months, this reduction in stress and anxiety also catalyzes the evolution of new thinking patterns. Ana is now less worried, calmer, and more rational. She starts to view things differently and ruminates less.

Without her being consciously aware, she also acts differently. She has set her room in order and has started to pay attention to a healthy lifestyle. She now laughs more often. One day, she contacts that friend she has not talked to in a long time, starting to build the high-quality relationships she needs so deeply. Another day, she takes up an old hobby.

Soon, she feels more positive about herself and about life in general. Hopelessness and helplessness are (mostly) gone and a new outlook on life started to develop. More and more she tends to like her story and the character she plays in it. She now also has the necessary self-confidence to go out and productively tackle whatever needs to be tackled, which before seemed impossible.

Over the course of only a few months, she makes major progress. A lot of the changes were catalyzed by a change in neurobiochemistry. However, Ana herself also played an important part. In a way, starting to take the antidepressant was like tuning up the motor, but if the car had not gone anywhere it would not have mattered much.

While this story may seem like a fairytale, I know a handful of cases that went somewhat like this – more detail in my article on SSRIs here.

So, when it comes to the “mechanism of action” of antidepressants all of the following are independently important:

- changes in moment-to-moment experience

- changes in thinking patterns and how she views and frames things (“inner life”)

- changes in her habits and life circumstances (“outer life”)

Even if Ana stops treatment, due to a combined effect of all of these things, the effects on her behavior and personality will quite likely persist for some time, especially if mental and behavioral habits are maintained by additional deliberate effort on her side.

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

My thoughts and outlooks strongly depend on my neurobiology

A couple of years ago I experimented with low doses of irreversible MAO-inhibitor. After taking a single low dose of phenelzine, after 3-4 days (the time the molecule takes to work), I felt a minor version of how I felt on MDMA. I suddenly made lofty plans and my outlook on my future was irrationally positive. I was deeply happy and content.

After a couple of days in this state, my neurobiology swung in the opposite direction. As the MAO-blockade wore off (and my neurotransmitter systems had counter-regulated aiming to restore equilibrium), my thoughts and outlook on my future were irrationally negative. Instead of euphoria, I was filled with anxiety and despair.

Out of curiosity, I repeated this experiment a couple of times. It flabbergasted me every single time and telling myself “Just chill, this is biology.” barely helped – even though I knew exactly what was happening neurobiologically.

I want to end this section with a quote by the philosopher David Pearce:

“Today, meanwhile, many people find it hard to get out of bed in the morning. Given the prevalence of chronic dysthymia, anhedonia and low-grade depression in even the “well” population at large, such inertia is scarcely surprising. Why bother to exert oneself if the payoff is so meagre? Depressive and unmotivated people are likely to find life “meaningless”, “absurd”, “futile”. Nihilistic thoughts and angst-ridden mindsets are common. Feelings of inadequacy and failure can haunt the ostensibly successful. And the world is full of walking wounded whose spirit has been crushed. Conversely (and for evolutionary reasons, less commonly), hyperthymic or euphorically hypomanic people tend to find life intensely meaningful. A heightened sense of significance is part of the texture of their lives. If our happiness is taken care of – whether genetically, pharmacologically, or electrosurgically – then the meaning of life seems to take care of itself.”

While I do not necessarily agree with everything (namely, that happiness is just neurobiology), he has a point.

I discuss my experience with depression in more detail here.

Related articles:

Sources & further reading

- Scientific review: Happiness is a personal(ity) thing: the genetics of personality and well-being in a representative sample

- Website: Reddit – r/depression

- Opinion article: David Pearce – Utopian Pharmacology

Disclaimer

The content available on this website is based on the author’s individual research, opinions, and personal experiences. It is intended solely for informational and entertainment purposes and does not constitute medical advice. The author does not endorse the use of supplements, pharmaceutical drugs, or hormones without the direct oversight of a qualified physician. People should never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something they have read on the internet.