I always thought there has got to be a neuropharmaceutical out there that makes me feel and perform better than baseline. One of the only pharmaceuticals that ever worked for me (n=1) in this regard was a low dose of moclobemide.

Moclobemide is a poorly known all-rounder. It boosts energy levels, mood, sleep, and hormones. On the therapeutic side, it helps with anxiety, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, depression, a lack of energy, and ADHD symptoms. All while not blunting emotions, worsening libido, or dysregulating appetite in a way many other antidepressant drugs do.

Moclobemide is neither widely known nor widely used. While it is not even available in the US, it is a first-line antidepressant in Australia and some northern European countries. Anecdotally, some cyclists use moclobemide during the Tour de France because it does not show up in any drug screening (unlike most stimulants).

Personal experience

I live in a simulation of reality generated by my brain. Neurotransmitters function as the simulation’s hyperparameters. In the only life I can be sure of having, I want these hyperparameters to be the best they can be, which is a win-win for both me as well as others. Next to lifestyle interventions and hormones, moclobemide is perhaps the best all-in-one solution I have so far found to help with this.

I have tried moclobemide twice, each period separated by around one year. The first time, I was kicked into “hyperawareness mode” already on the first day. I remember going for a run and realizing how many smells there are. Also, the colors appeared much more vivid than normal. I attribute this to the increase in noradrenaline.

This state of “hyperawareness” continued for the next couple of weeks. The intense presence helped me realize the misalignment between my life and values. It also showed me how much I operate on autopilot in my day-to-day activities. It also made me reconsider my life priorities given that there is a fair chance that over 50% of my time in this universe might be already gone (due to various X-risks possibly being around the corner).

In sum, my whole experience with moclobemide felt like a weak psychedelic trip lasting for a whole month.

Unfortunately, moclobemide also triggered a state of anxiety, which I rarely experience otherwise. To be fair, I also had my finals coming up, and my mother had developed breast cancer. Because of the increase in anxiety, I stopped moclobemide after about six weeks. Though, I took a lot of valuable lessons with me that ended up benefitting me down the line.

After a year or so, I decided to give it another chance. At the time I did not foresee that I would end up taking moclobemide for about one and a half years, by far the longest time I had ever taken a neuropharmaceutical drug.

I started with only half of the lowest prescribed dose and over the course of two weeks moved up to 150mg per day, split into two daily doses. The activating effects were much weaker compared to my first experience. Moclobemide boosted my mood, energy, and focus just as I had hoped.

Interestingly, this time there was no anxiety. I have a few theories about this. The most plausible explanation is that I had started taking semaglutide a couple of months before, which may have normalized my sympathetic tone. As a result, my second trial with moclobemide may have been gentler on my noradrenaline levels.

Alternatively, my objective life situation had been different with few things to be anxious about. Or it may have been because of something else. Regardless, my second experience was much different than the first.

Out of all of the antidepressants and stimulants I have tried over the years, I liked moclobemide the most. If I were to describe what being on moclobemide felt like to me, I would say I am just a little more “me”. Among my life goals are five adjectives: vital, mindful, compassionate, flexible, well-rounded. Moclobemide seemed to help me with all of these.

Another thing I loved about moclobemide was that it made taking stimulants obsolete. Firstly, it cannot be combined with anything that acts on the serotonergic or noradrenergic systems, and secondly, my energy and mood were usually good enough that I rarely “needed” anything else. On moclobemide, I laughed much more and I also became more extroverted. These two effects persisted throughout the time of taking it.

However, there were major downsides that would ultimately lead to me quitting moclobemide.

Something I realized early on, was that moclobemide decreased my brain’s capacity for generating negative emotions. If my normal ratio of positive to negative thoughts & emotions is 50/50, on moclobemide, it was 90/10.

I believe that having a healthy amount of negative thoughts and emotions is overall net conducive to living a meaningful life, and making me “happier” in the short term may contribute to being less happy in the long term because negative emotions are often signals to be acted upon. However, I cannot act on negative emotions I do not have.

I am generally not an anxious, fearful, or worrying person, but on moclobemide, my anxiety, fear, and worry were almost completely gone. While this may seem desirable at first, eventually it may end up being problematic in many situations.

For example, when my girlfriend and I argued, it took perhaps five minutes for me to return to my cheerful state, leading to her believing that I am “socially inept”, which strained our relationship a couple of times. Furthermore, a brain incapable of generating anxiety is also incapable of generating empathy, which is not overly conducive to interpersonal relationships.

While I had more energy and I was almost always in a decent mood, on moclobemide I was also less “deep” and less capable of feeling profound feelings, including both positive or negative peak experiences. For example, throughout my time on moclobemide, I rarely experienced euphoric joy or distressing sadness. I believe that a healthy life fully lived should include intense emotions, which moclobemide seemed to prevent.

On moclobemide, I also feel that my intelligence took a hit and I was less capable of thinking thoroughly about things. Normally, I think hard about things, which may be a consequence of high cognitive unease. However, on moclobemide, my cognitive unease was mostly gone and I realized that my thinking process was more shallow.

I have not yet made up my mind about how much of my cognitive abilities I’m willing to sacrifice in exchange for greater (perceived) happiness.

Furthermore, on moclobemide, I was more “civilized”. For example, I was less bothered by things or less obsessed with how things work. Overall, moclobemide made me more “normal”. I have not yet decided whether that is a good thing or a bad thing.

If I were depressed, this would be a different matter, but my baseline is already about average-happy, and improving my mood even more is a double-edged sword that comes at the price of tradeoffs.

In summary, I always wanted to be happier and less lost in thought. Moclobemide helped me to achieve this, though, I am unsure whether the 2nd and 3rd order consequences of this are a net benefit or a net harm.

I have experimented with dosages ranging from 37.5mg per day to 450mg per day. For me, the “best” dosage was 37.5mg (a quarter of a tablet) taken twice per day (morning and noon). At this dosage, I had a decent uptick in energy and mood while not interfering too much with cognition and emotionality. For reference, an average dose for depression or anxiety is 300mg per day. However, MAO inhibitors have a very non-linear dose-response curve.

At higher doses, my cognition and emotions are blunted and I feel “nice” all of the time. However, at subclinical doses, my spectrum of emotions is left intact. Furthermore, on it, I have slightly more energy, a slightly better mood, slightly more confidence, and a slightly greater zest for life.

I guesstimate that the compound interest of moclobemide-induced changes in my near and distant future may have been worth the many years of self-experimentation with antidepressants.

In terms of side effects, I had none, other than some restless leg syndrome at the beginning, and some anxiety the first time I tried it. However, moclobemide is not without risks. It interacts with every drug that affects noradrenergic and serotonergic systems, including cough & cold remedies.

Both friends and I sometimes use low doses of moclobemide on an as-needed basis. In my experience, very low doses (e.g., 25-50mg) taken occasionally give a natural boost in energy and mood that lasts all day. Unfortunately, there is a withdrawal that happens around 24h after.

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

Moclobemide appears to lower my IQ

I am currently off moclobemide because it seems to reduce my cognition. I discuss this in more detail here.

How it works

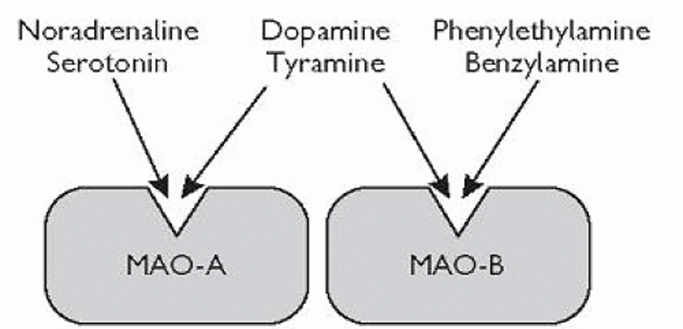

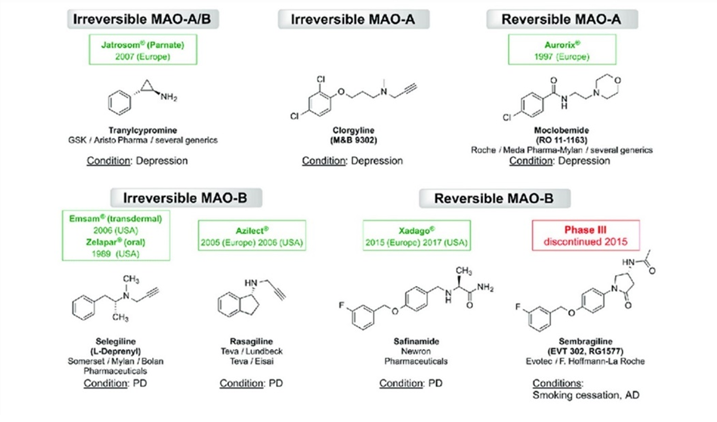

Monoamine oxidase enzymes (MAO) metabolize (break down) monoamines. There are two isoforms of the enzymes:

- MAO-A, which is expressed ubiquitously throughout the body, is accountable for a sizable share of monoamine transmitter breakdown (serotonin, dopamine, noradrenaline).

- MAO-B, which is predominantly located in dopaminergic and serotonergic neurons, is responsible for the metabolism of dopamine as well as trace amines.

Moclobemide is a reversible inhibitor of MAO-A (RIMA). Inhibiting MAO-A leads to a strong rise in serotonin and noradrenaline levels throughout the body. Its effect on dopamine is more complex (explained shortly).

If monoamine oxidase is inhibited, cellular stores of monoamines increase. Consequently, more monoamines are released per neuron firing. This contrasts with reuptake inhibitors such as SSRIs, bupropion, or modafinil.

With reuptake inhibition, monoamines are “locked” into the synaptic cleft, and the natural rise and fall in concentration is blunted. Conversely, with MAO inhibitors the natural rise and fall in concentration is preserved, there are simply more monoamine molecules released. Therefore, MAO inhibitors are, and feel, more “natural” because the resulting increase in monoamines simply amplifies the natural release.

Moclobemide is regarded by many as a “weak” MAO inhibitor that does not work (discussed shortly). For severely depressed people, it is likely not potent enough. However, in the right context and person, moclobemide can be quite an effective drug.

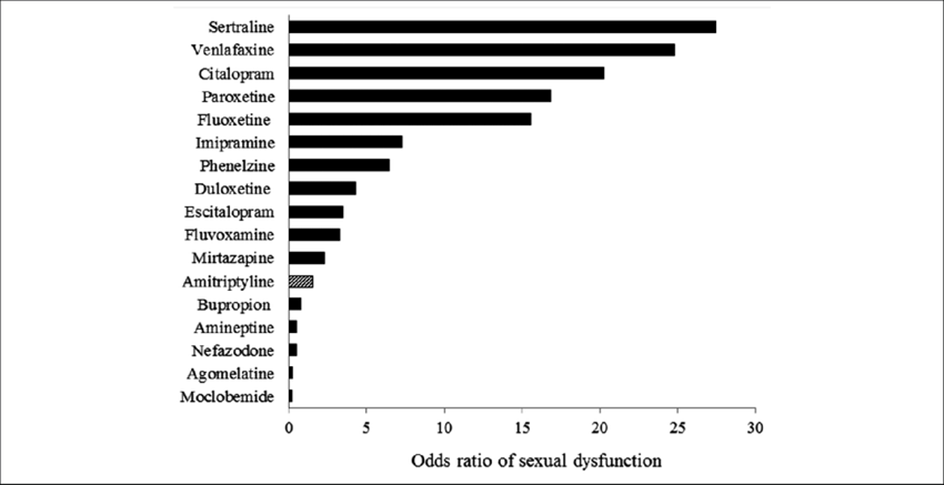

It is usually well tolerated (in fact, one of the best-tolerated antidepressants), it feels “natural”, and it has little to no withdrawal symptoms. Furthermore, in contrast to most other antidepressants on the market, it improves libido, improves sleep, and does not mess with appetite.

Also, uniquely among antidepressants, it improves levels of sex hormones, cortisol, and growth hormone. Because of this and other reasons, moclobemide is, in my opinion, a rarely considered but great option for people with low energy levels, especially as it does not have the tolerance-dose-escalation cycles that plague stimulants.

Reportedly, people who are usually “sleepwalking” through life are suddenly wide awake, particularly at the beginning of treatment. They wake up full of energy and are functional without coffee. Despite usually being “destroyed” at night, many even start to have trouble falling asleep.

These effects may be in part explained by the upregulation of sympathetic nervous system activity and the HPA axis. Many of these activating effects gradually decrease after a couple of weeks and settle to lower levels – but are presumably still above baseline.

Out of all antidepressants, moclobemide also has the least effect on sexual function. In fact, for many people, moclobemide stimulates sex drive and libido.

Why is it that SSRIs kill libido but moclobemide increases libido – despite both increasing serotonin levels? It may have not so much to do with dopamine and noradrenaline but rather with the specific way moclobemide increases serotonin vs. the way SSRIs increase serotonin.

As explained above, moclobemide increases vesicular 5HT content whereas SSRIs “lock” serotonin into the synaptic cleft, resulting in different amplitude changes in synaptic serotonin concentration. This is presumably also the reason why modafinil and selegiline “feel” vastly different – despite both selectively increasing dopamine levels.

Moclobemide is also an option for people with ADHD, particularly when ADHD is comorbid with depression, anxiety, or OCD. However, it is rarely prescribed because people with ADHD often consume recreational drugs, which when combined with moclobemide leads to severe side effects.

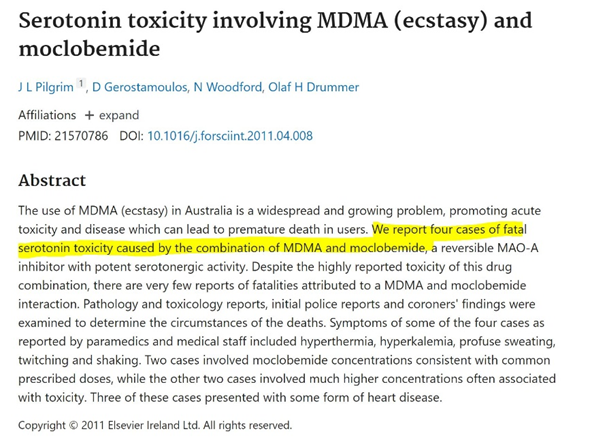

If moclobemide is combined with molecules that act on the serotonergic or noradrenergic system (modafinil and caffeine are fine), this can lead to serotonin syndrome or a hypertensive crisis respectively, both of which can be fatal. For example, if one takes MDMA while on moclobemide, one will likely die.

Even though moclobemide’s half-life is quite short (2-4 hours), the MAO-A inhibition lasts for about 12-24 hours. I took moclobemide in two divided doses per day. The first dose after waking up and the second dose about 5-6 hours later.

We are all different

In the same way, it holds for other neuropharmaceuticals, it is hard to predict whether someone responds favorably to moclobemide or not.

- There is a significant percentage of people who feel little to nothing. This may have to do in part with endogenous differences in the quantity of MAO-A expression, setpoints of individual monoamine transmitters, or with little self-awareness.

- Some get potent antidepressant and stimulant effects for the first few weeks only but then moclobemide “poops out”. Others can be on it for years and seem to get sustained benefits.

- Some do better on higher doses (600mg +), and some do better on lower doses (e.g., my favorite dosage was 75mg per day).

- Some people get agitated, anxious, and restless (especially at the beginning), while others get tired and sleepy.

- For some people, moclobemide can cause apathy and cognitive dullness, especially at higher doses, for others it does not.

In cases of treatment-resistant depression, the “gentle” moclobemide is likely not going to cut it, however, this does not detract from its potential usefulness as a general “life enhancer” for sub-depressive, anhedonic, and dysthymic folks. Because “gentleness does not suit everyone” (credit: David Pearce), irreversible MAOIs are discussed later.

Dosing

Dosing with moclobemide is tricky. For me, increasing from 150mg to 300mg worsened my energy levels. Furthermore, I felt dumber, less confident, my brain was slower, and I had less “personality” (more flat, listless, somewhat anhedonic, less sharp, and witty). I also had less fire or zest in me, and life felt somewhat colorless. This reminded me of the amotivational syndrome described by people on SSRIs.

The addition of a very low dose of rasagiline (an irreversible MAO-B inhibitor) abolished all of this already on day one.

How is that? If MAO-A inhibition is below 50-60%, dopamine levels increase. However, if MAO-A inhibition exceeds 80% (without concomitant inhibition of MAO-B), dopamine levels are thought to fall sharply, likely mediated by serotonin signaling exceeding a certain threshold and inhibiting dopamine-producing midbrain neurons.

The crucial importance of dopamine is discussed here.

Three options may prevent dopamine levels from falling upon moclobemide administration:

Option #1: Low-dose moclobemide (75-150mg/day)

MAO-A is inhibited by only 50-60%. This will elevate all major monoamines (including dopamine), though not as strongly compared to higher doses. This was the dosage range I responded best to. I responded better to 75mg than to 150mg. As so often, more is not always better.

Option #2: High-dose moclobemide (900mg-1200mg)

At this dose, MAO-A inhibition reaches about 80-90% and dopamine levels would take a hit. However, at high doses, moclobemide loses its selectivity, and MAO-B (responsible for dopamine metabolism) also starts to be progressively inhibited preventing dopamine signaling from falling. At this dosage, a low-tyramine diet becomes relevant.

Option #3: Medium-dose moclobemide (300mg – 600mg) + a low-dose MAO-B inhibitor

At “no-man’s-land-doses”, MAO-A is inhibited by 70-80%, while MAO-B is left mostly untouched. Consequently, dopamine levels take a hit. Unfortunately, this is the dose range most doctors prescribe moclobemide to their patients. I suspect that this may be the reason behind many psychiatrists claiming that moclobemide is ineffective.

Back when I was at this dose range, I would use a very low dose of rasagiline (0.1mg per day) to counteract the decrease in dopamine levels and to achieve a more balanced monoamine profile.

A fixed dosage combination of the two (e.g., 150mg moclobemide + 0.05mg rasagiline per pill) could have the potential to become a new antidepressant drug that may fill an existing treatment gap. While not as potent as the older irreversible MAOIs, this comes with much-reduced risks (e.g., hypertensive crisis) and side effects (e.g., hypotension, erectile dysfunction, insomnia).

Of note, selegiline is a suboptimal substitute for rasagiline as it metabolizes into l-methamphetamine, which is potentiated by the moclobemide. Rasagiline on the other hand does not have any amphetamine-like byproducts. In fact, this was the reason why rasagiline was created in the first place.

What MAO-A inhibition vs. MAO-B inhibition feels like (for me)

The higher I went in moclobemide (a selective MAO-A inhibitor), the calmer, stiller, and more boring my mind became, which was also reported by friends of mine. Conversely, rasagiline (an MAO-B inhibitor) has the opposite effect on me. The higher I go, the more restless, driven, and more exciting my mind becomes. Whereas MAO-A inhibition makes me more present-oriented, content, and calm, MAO-B inhibition makes me more future-oriented, edgy, and impulsive.

Thoughts on irreversible MAO inhibitors

Irreversible MAO inhibitors such as tranylcypromine (an amphetamine derivative) and phenelzine are among the most powerful antidepressants known to mankind (also known as “nuclear” antidepressants) and they are one of the few antidepressants that have potent mood-elevating effects even in non-depressed people, often inducing hypomania-like behavior.

As a quick piece of info, “irreversible” does not mean lifetime-irreversible but rather irreversible in the sense that inhibition renders the enzyme useless. However, MAO enzymes have a natural turnover time of about 2-3 weeks, and thereafter, MAO levels will be back to baseline if one stops taking the inhibitor. So, “irreversible” MAO inhibitors inhibit MAO-enzymes irreversibly for only a couple of weeks.

Two friends of mine have experimented with literally every antidepressant under the sun, and low doses of irreversible MAO inhibitors were the only thing that, according to them, really helped their depression. One of them was talking the ears off of everyone when he first started. Both use much lower than “therapeutic” doses (e.g., 2.5-10mg of tranylcypromine instead of 60mg).

The use of MAOIs has been declining sharply over the last couple of decades, in part because of a lack of industry support (the patent expired decades ago), and in part because of the life-threatening reactions these drugs tend to cause. While some of the fear is surely overblown, some of it is surely warranted.

They carry two major risks: serotonin syndrome (if combined with serotonergic molecules) and a hypertensive crisis (if combined with the wrong foods or stimulants). In fact, one of my friends had three closed-angle glaucoma attacks within the first two months of starting therapy, likely caused by not paying sufficient attention to dietary tyramine. Because keeping his eyesight is important to him, he had to stop.

Irreversible MAO inhibitors have a lot more side effects than the “gentle” moclobemide, the most troublesome of which are insomnia, debilitating hypotension, and fatigue.

If irreversible MAO inhibitors elevate all major monoamines, why then do they result in fatigue? People on moclobemide rarely report fatigue, and neither do people on MAO-B inhibitors. Therefore, irreversible inhibition of MAO-A is the most likely culprit.

While there are many theories, the only one I find plausible is that the fatigue is related to the accumulation of octopamine from the improper metabolism of noradrenaline due to the irreversible inhibition of MAO-A. Octopamine is considered a “false” transmitter, incapable of activating noradrenergic alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptors.

As octopamine accumulates, it takes the place of noradrenaline in synaptic vesicles. It gets released when noradrenaline is supposed to be and is incapable of activating adrenergic receptors, resulting in functional suppression of adrenergic activity all over the nervous system.

Irreversible MAO-inhibitors are essentially having a sympatholytic action, and the body-wide decline in noradrenaline signaling leads to an inability to vasoconstrict properly, resulting in severe orthostatic dysfunction and hypotension. In fact, in the beginning of treatment, many people report that they nearly pass out frequently.

Furthermore, the sharp drop in brain noradrenaline levels results in fatigue.

While irreversible MAOIs can bring about spectacular remission of depression in treatment-resistant cases, they come with great side effects (low blood pressure, fatigue, insomnia) and a real and substantial risk of experiencing a hypertensive crisis or a serotonin syndrome at least once during the course of treatment, both of which can be deadly.

Irreversible MAOIs are perhaps the hardest antidepressants to start (e.g., debilitating hypotension, insomnia, the necessity to avoid tyramine and a host of other drugs) and the hardest to stop (e.g., crippling anxiety, nightmares, paranoia, delusions). This is very different from moclobemide, which is easy to start and easy to stop.

Last but not least, irreversible MAO inhibitors tend to eliminate empathy – with potentially adverse effects not just on the life of the user, but possibly also on the people the user interacts with.

Thoughts on combining MAO-inhibitors + stimulants

Some doctors like to prescribe stimulants to patients on irreversible MAO inhibitors to combat the hypotension and lethargy. Even though, if done cautiously, it may be safe in terms of blood pressure and acute toxicity, the synergistic elevation in monoamine levels from combined reuptake inhibition + inhibition of monoamine metabolism may pharmacologically replicate some neurodegenerative aspects of manic episodes, causing low-level chronic excitotoxicity, potentially resulting in early-onset dementia.

Even though there is currently no scientific evidence for this (the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence), there is plenty of evidence from animal studies and observations in human amphetamine abusers that high-dose amphetamine is excitotoxic causing widespread brain damage, as discussed in detail here: Are (Therapeutic) Amphetamines Neurotoxic?

An MAO-inhibitor + low-dose amphetamine may be quite the same, regardless of the neuroprotective effects of MAO-B inhibition.

Instead of using the potentially neurotoxic combination of MAOIs + stimulants, one of my friends combated the MAOI-associated hypotension and fatigue by cycling the direct sympathomimetic drugs midodrine (an alpha-1 agonist) and low doses of clenbuterol (a beta-2 agonist).

If MAO-A is reversibly inhibited (e.g., moclobemide), octopamine will still be metabolized due to the on-off rate (reversibility) of the inhibitor at MAO-A. Therefore, RIMAs do not share the blood pressure-lowering effects of irreversible MAOIs, and they usually also do not have the fatigue associated with irreversible MAO inhibitors.

Similar things hold true for tyramine, which is a dopamine-noradrenaline-releasing agent present in some foods. Tyramine is normally eliminated by MAO-A or MAO-B in the gastrointestinal tract, but if both enzymes are inhibited irreversibly, this can cause tyramine to enter the circulatory system, and induce a release in catecholamines from sympathetic nerve endings resulting in a hypertensive crisis (severe increase in blood pressure), which often results in ER visits by MAOI patients.

For reversible MAO-A inhibitors (RIMAs), this is much less of a concern and mostly limited to bothersome but clinically insignificant hypertensive reactions. RIMAs also cause much less insomnia than irreversible MAO inhibitors.

MAO inhibitors are different.

Unfortunately, medicine is stuck with drugs that affect transmembrane signaling and the lion’s share of neuropharmaceutical interventions are based on it.

However, the key to bringing about true and lasting change is likely not the superficial transmembrane domain but rather the “deep” intracellular domain. Given that gene therapies are not yet available, currently, the only available intracellular interventions are hormones and MAO inhibitors (disregarding “mindset” and emotional work).

Regarding the latter, it is paradoxical that the only class of antidepressants that does not work on transmembrane receptors is also the oldest one. And regarding the former, I hope that psychiatry (and medicine in general) will someday recognize (and utilize) the power of hormones – even though they cannot be patented. Hormones are discussed in more detail here.

Other experience reports

For a discussion of the molecular correlates of well-being, and links to accounts of various related molecules I have experimented with, read here.

For a full list of experience reports click here.

Sources & further information

- Anecdotes: Reddit – r/MAOIs

- Scientific review: Moclobemide – An Update of its Pharmacological Properties and Therapeutic Use

- Website: Wikipedia – Moclobemide

Disclaimer

The content available on this website is based on the author’s individual research, opinions, and personal experiences. It is intended solely for informational and entertainment purposes and does not constitute medical advice. The author does not endorse the use of supplements, pharmaceutical drugs, or hormones without the direct oversight of a qualified physician. People should never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something they have read on the internet.