Cancer is called “the emperor of disease” for a reason. To some degree, no matter what I do, my likelihood of developing cancer at some point is between 30-60%. Out of all of the things that are known to kill humans, cancer is perhaps the hardest to figure out, in part, because it also depends on bad luck.

How does cancer arise?

There are a variety of causal associations between cancer and genetics, pathogens, or environmental exposure. However, most cancers are due to random mutations because of “bad luck”.

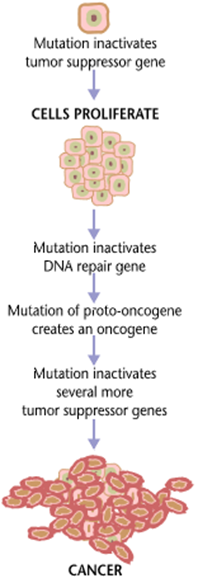

Cancer is fundamentally caused by genetic mutations, which cause a cell to behave in ways it should not. In the case of cancer, this means “growing and proliferating” at the expense of other cells. Cancer is like having a foreign parasite inside your own body, with the exception that the parasite is not “foreign” – at least not initially.

Because somebody else said it better than I ever could, here is what oncologist Keith Flathery said about the pathogenesis of cancer:

“The combination of mutations has to be dialed in the right sequence just like when you’re opening your gym locker, or you don’t get cancer. You’ve got to get your tumor suppressor early and in the right order before your activated oncogene comes along.

You’re randomly spinning a lock. You’re picking up lots of past permutations, not just true drivers, so these incidental mutations happen here and there. As that’s happening, you finally click important components of the program. Along the way, some of those are actually mutations that are seen as foreign by the immune system.

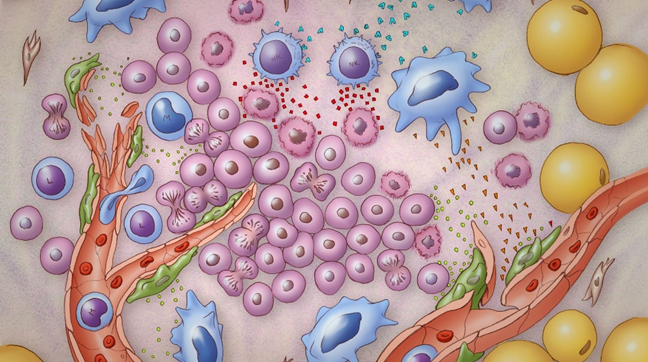

If they’re too far out there, then they’re gone. It has to be a right kind of genetic alteration that will give the cell what it needs to be able to proliferate abnormally, be able to sustain a lot of DNA damage as it accumulates, and not commit suicide as a consequence, and be able to handle all of the other adverse features and filters of a tumor micro-environment.

By the time the tumor mass is clinically relevant, there isa mass of about one billion cells. They have had to deal with an incredible array of defense mechanisms and cellular brakes. Tumor cells are evolutionary warriors by this point and using our chemotherapies is like poking them with a stick. Some subpopulations of those cancer cells will slow down and die with conventional chemotherapy, but many of them are pre-wired. They were hardy to begin with.

They got there through a hard-earned evolution under selective pressure of the immune system and adverse metabolic environment, and they used all of the tricks up their sleeve to reprogram themselves to be able to survive in these harsh environments. You throw in another harsh environment reagent in the form of chemo, not surprisingly, these things were already basically hardwired to be able to survive yet another insult.”

For people interested in cancer biology and treatment I recommend the full podcast.

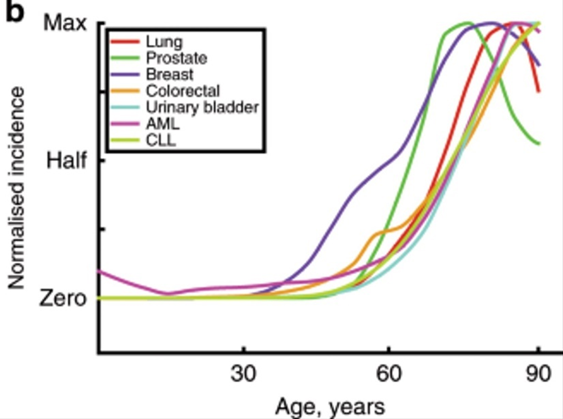

There are a number of reasons why my risk of developing cancer increases non-linearly as I get older:

- As I get older, my genome is more susceptible to injury (e.g., DNA-repair machinery and other cellular housekeeping functions degenerate due to aging)

- The older I am, the more of these genetic “hits” (cancer-causing mutations) I have already accumulated, and the fewer additional hits are needed for cancer to develop.

My immune system will gradually lose some of its steam (“immunosenescence”), and the ability with which it detects and dismantles early cancer cells progressively declines.

By the time cancer becomes clinically relevant, most cancers are evolutionary warriors, with a massive array of defense mechanisms. Eventually, once a cancer has become sufficiently advanced, the lucky subclones will just laughingly mutate their way around everything we throw at them.

Currently, close to 100% of the time, metastatic cancer (of a solid organ) is deadly (with very few exceptions), and survival can only be prolonged slightly (a few weeks to months for tens of thousands of dollars). Hence, once there is metastasis, there is little that can be done. So, the most efficient & effective way to go about it is undoubtedly prevention.

Cancer prevention

Currently, there are two things people can do to increase the odds of not dying from cancer.

Step 1: Trying not to get cancer

We know of a handful of things that undoubtedly increase cancer risk. These include smoking (thought to be responsible for about 30% of cancers), obesity (especially the associated hyperinsulinemia), exposure to certain carcinogens (hint: it is not red meat), and a number of infections (e.g., HPV, HCV, HBV).

Step 2: Looking for cancer early

When it comes to cancer, early detection is the name of the game because it is about the only thing that has worked thus far (aside from a couple of non-universal breakthroughs for a specific subset of cancers). Currently, this includes keeping an eye on a host of plasmatic tumor markers, and occasionally performing screening procedures (such as colonoscopy, measuring PSA levels, and full-body MRIs).

In the (near?) future, progress in the x-omics section (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) will presumably revolutionize cancer detection because they may yield valuable biomarkers. For example, “liquid biopsies” will be fine-tuned with machine-learning approaches (“artificial intelligence”). These biomarkers will then be layered with cutting-edge scanning and imaging techniques.

By layering multiple of these technologies on top of each other, perhaps with AI algorithms, we will hopefully get to a point where we can catch most cancers already in the early stages, long before they are ever in a position to leave the primary cancer site. Instead of spending 5% on prevention and early detection, we should spend 50% on it.

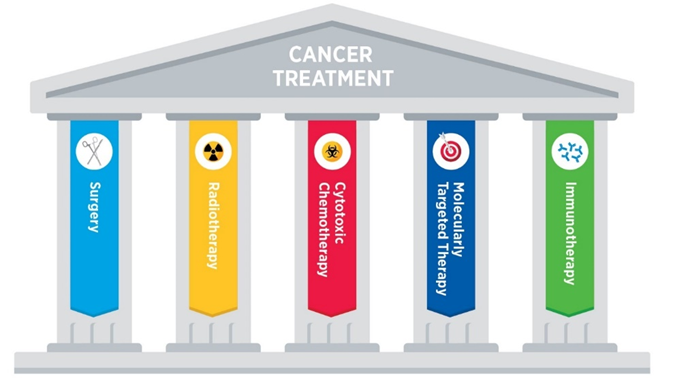

Once advanced cancer is there, it is probably best to go after multiple avenues simultaneously, including surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, immunotherapies, metabolic therapies, epigenetic regulators, and growth factor receptor modulators.

Because this section is already quite long, I discuss liquid biopsies, immunotherapies, and potential improvement in the way current chemotherapy is done, in more detail here: Exciting New Avenues to Revolutionize Cancer Treatment

Tactics I follow aimed at preventing cancer

- Measuring stuff

- Rapamycin

The above is only a fraction of the article. This article is currently undergoing final revisions and is expected to be published within the next few weeks to months. To receive a notification upon its release, sign up for my newsletter.

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!