Depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide. People who have never been depressed can hardly imagine what it means to always “feel like shit” and to live with a constant background of depression.

Major depression is not just some made-up term for people having a bad day – it is a serious mental state, characterized by a severe imbalance in neurotransmitters and neuroplastic processes, which makes the individual emotionally unstable, unable to focus or to think clearly, kills joy, and removes interests (sometimes including one’s own survival).

Even though not a helpful explanation, it is generally thought that “depression is brought about by a combination of biological, psychological, and environmental factors”. It seems that every depressed person has his/her own somewhat unique mix & match variation of causes as well as symptoms.

Sometimes, depression is caused by endogenous changes that seem to happen for no reason, other times, depression is caused by external life events, and most of the time it is a combination of the two.

In this article, I discuss the basic principles behind depression, its cause, and its treatment. The practical aspects are discussed here: What Kind of Antidepressant Should I Choose?

Different forms of depression

There are various forms of depression. The most common are anxious depression (also called melancholic depression) and endogenous depression (also called atypical depression). Though in reality, there probably are many more different spectra, and combinations thereof, of depression.

Depression is defined by a deviation from baseline. For example, if a generally happy and cheerful person experiences depression, their happiness and cheerfulness (their “baseline” state) is depressed – which literally means “pressed down”.

Unfortunately, true biological depression, such as the two forms of depression discussed shortly, is usually lumped together with many other states of “prolonged subjective suffering”, which may or may not be rightfully called depression from a biological perspective.

Melancholic depression

Melancholic depression is characterized by low mood, hopelessness, and anxiety about the future. This is the form of depression that most people think of when they think of depression.

Melancholically depressed individuals cease to experience pleasure or joy from things they normally would enjoy (“anhedonia”). While some patients are sad and anxious, others say they are feeling absolutely nothing inside, positive or negative. HPA-axis activity and cortisol levels are generally high in this form of depression. A major risk factor for this kind of depression is a shitty subjective effort-reward imbalance (“I am working hard but nothing comes of it.”) and large amounts of stress.

Atypical depression

Atypical depression is characterized mostly by very low energy levels (instead of a very low mood). The person needs to sleep a lot (hypersomnia), gains weight, and simply moving around is often perceived to be an onerous task (“leaden paralysis”). HPA-axis activity and cortisol levels are typically low in this form of depression.

This form of depression is less common than melancholic depression and is thought to have a stronger genetic underpinning. “Atypical” depression is somewhat of a misnomer that implies that this kind of depression is “weird” or rare – it is neither. This form of depression responds well to MAO inhibitors.

Evolutionary theories of depression

Does (biological) depression serve an evolutionarily adaptive function or is it a true dysfunction? There are arguments to be found for both sides.

Some researchers argue that the capacity for depressive behavior, even though personally unpleasant, was adaptive in our ancestral environment. Many theories have been put forth, of which I will now briefly introduce three. These theories are not mutually exclusive.

“Stress hypothesis”

Some researchers believe that biological depression may have evolved as a protective mechanism to prevent people from running themselves into the ground. According to this theory, prolonged stress triggers biological depression (a downward deviation from baseline) to “help” individuals let go of unattainable goals and/or withdraw from desperate situations.

If an individual’s energy and mood deteriorates she is more likely to let go and withdraw. Conversely, if an individual’s energy and mood did not deteriorate, she might continue to overexert herself and die. Indeed, prolonged stress (i.e., perceived effort) seems to be one of the greatest risk factors for developing depression.

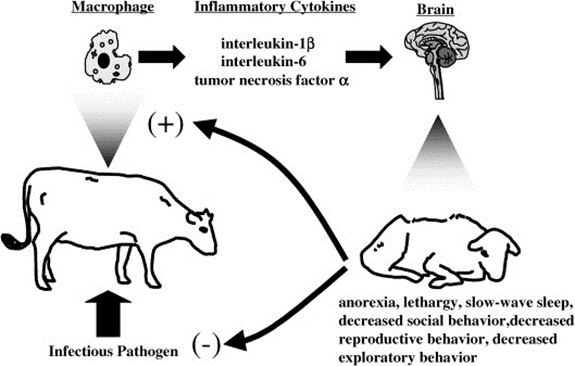

“Inflammation hypothesis”

Certain subtypes of depression are due to sickness behavior. “Sickness behavior” refers to a set of behavioral and mental changes that occur in response to an infection or inflammation.

Sickness behavior is characterized by a range of symptoms, including brain fog, fatigue, lethargy, lowered mood and self-confidence, anhedonia, a desire to withdraw, and altered sleep and appetite. These changes are thought to be an evolutionary adaptation that enables the body to conserve energy and focus on fighting infection or inflammation. Furthermore, it is thought that “sickness behavior” also induces a withdrawal from group living, which would help the group as well as prevent ostracization of the individual.

Indeed, many of the genes associated with depression are involved in inflammation and immune regulation. I discuss this in more detail here (Ibuprofen) and here (Low-dose Naltrexone).

“Rank-theory hypothesis”

Some researchers speculate that depression may have proved useful in dominance conflicts that are unlikely to be won. According to the “rank theory of depression”, sustained melancholy, withdrawal behavior, and a fixation on personal shortcomings and insufficiencies may ensure that the weak “keep their heads down” and don’t overreach themselves, which may prove evolutionarily fatal.

The rise of depression and anxiety in young people coincides with the advent of social media, and there is probably a causal connection at play. Social media constantly floods people with “evidence” that many others have it better. I like what Naval Ravikant has to say about it: “Social media make celebrities of all of us. And celebrities are the most miserable people on Earth.”

According to this theory, depression may represent a fitness-enhancing adaptation to group living. Indeed, if individuals are “losing” in life, they are more likely to develop depression. In support of this may also be the fact that adolescents are often depressed (because most adolescents are not on top of the hierarchy – aka the cool kids). Further support for this theory is evidence that antidepressants may overturn dominance hierarchies in relationships.

Whether depression is a final common pathway of all of the above, or whether all of the above only superficially and phenotypically resemble each other, is currently not known, in part because it is hard to test.

Differentiating depression and “suffering”

Regardless of evolutionary theories, it is important to differentiate between biological depression and “suffering”.

A psychiatrist once complained to me that what patients mean by “depression” does not always correspond to what doctors mean by “depression”. Most lay people consider depression to be a non-specific state of long-standing unhappiness, gloominess, low self-esteem, little joy, and just overall not being satisfied with their lives.

This is quite different from what the medical system means by “depression”, namely different forms of depression as distinct downward deviations from someone’s baseline state such as it is seen in melancholic depression, atypical depression, or bipolar depression.

Unfortunately, the term “depression” has taken on multiple meanings, and “depression” is used interchangeably to describe many different etiologically and phenotypically distinct states, which often results in confusion.

Given that we do not have useful biomarkers for depression, it is hard to tell whether someone is truly depressed (i.e., biological depression as a neuropathological process) or just “suffering”.

Nowadays, a lot of people claim that they are “depressed” and there are a lot of reasons why that might be the case, whether truly (biologically) depressed or not.

- Most of our survival needs are cared for and many people seem to lack purpose, which may cause a sense of meaninglessness because “I am not needed”.

- It seems that a lot of people have a hard time opening up to others, perhaps because they want to display a certain persona or maintain a certain façade to protect their status. In part because of this, many people seem to lack the proper, high-quality connections we humans need.

- Social media as mentioned above.

- Constant stress and pressure in the modern achieve-or-die environment is probably a big one.

- The overabundance of easy-to-get dopamine from video games, social media, porn, food, and drugs intended to fill the hole likely does not help either.

- Among the biological contributors are junk food, lack of high-quality sleep, lack of sunlight, lack of proper movement, and a lack of high-quality human connection (which I would classify as a biological need as well). I discuss these “basics” in more detail here.

However, given that antidepressants alter neurobiochemistry, and neurobiochemistry co-determines feelings, thinking patterns, and actions, antidepressants do not just help with “true” biological depression, but they may also help with non-depressive “suffering”, particularly insofar antidepressants can help people to make real-life changes. I discuss this in more detail here: What Kind of Antidepressant Should I Choose?

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

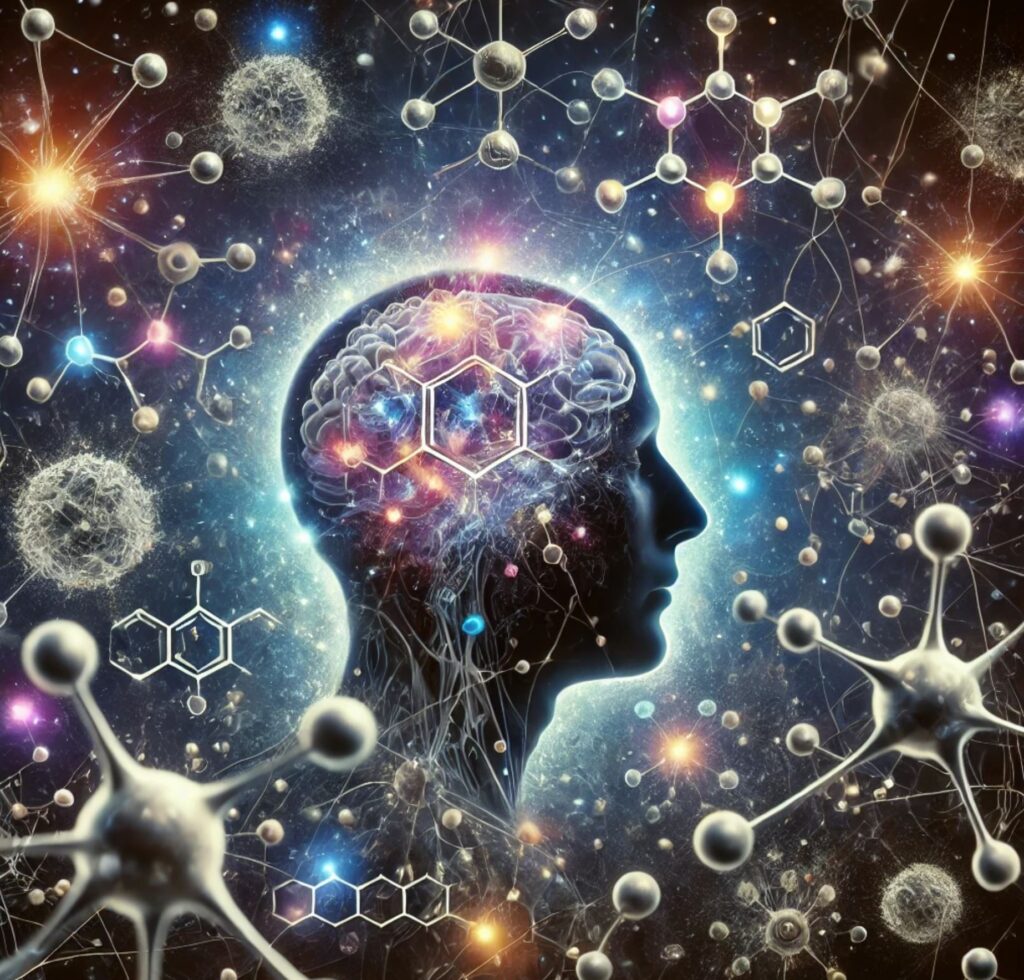

Neurobiology of depression – Monoamines and neuroplasticity

While evolutionary theories try to explain why depression exists, molecular theories try to explain how depression happens on a mechanistic level.

There are a variety of molecular theories of depression. Most of these are not mutually exclusive. I will only discuss two of these. The “monoamine hypothesis” and the “neurogenesis theory”.

In the 1960s it was observed that monoamine-depleted animals display the equivalent of depressive behavior. Upon reserpine administration, a drug that depletes monoamines (dopamine, serotonin, noradrenaline) by blocking the vesicular monoamine transporters (VMAT), animals become easily scared, withdraw, exhibit little novelty-seeking, and work less to obtain a reward. This change is quite instant.

The “monoamine hypothesis” of depression was born. It was postulated that low monoamines result in low mood, motivation, and energy levels. Inherently, the monoamine hypothesis makes a lot of sense and there is a lot to it. For example, when I drink coffee, I feel its effects on my energy & mood within 15 minutes.

However, it is not the whole story.

One of the major competing theories is the “neurogenesis theory” of depression. This theory is in part based on multiple observations:

- Ketamine is highly antidepressive (ketamine is discussed here). Background: Ketamine leads to a boost in neurogenesis.

- The administration of SSRIs often takes two to four weeks for someone to get better, despite monoamine levels increasing within hours.

- Travelling, and other forms of environmental enrichment, are highly antidepressive for many people. The boost in neurogenesis from all the novelty is one reason why many people have greater energy and mood while they are travelling.

The neurogenic hypothesis suggests that depression is at least in part caused by an impairment of the brain’s ability to birth new neurons in the hippocampus, one of the few zones where neurogenesis still happens to a significant degree throughout life.

The hippocampus is not just important for memory formation but also crucial to the regulation of stress, mood, and cognition. It turns out that monoamines (serotonin, dopamine, noradrenaline) increase neurogenesis in the hippocampus.

Neurogenesis is hypothesized to be an important part of the reason antidepressants work (even though, again, far from the whole story), and why they take some time to have an effect.

Both theories are not mutually exclusive. There surely is also an antidepressant response to antidepressants or recreational drugs even without any neurogenesis taking place. For example, after drinking coffee, most people report being happier for a short period of time – long before any neurogenesis could have taken place.

Similarly, recreational drugs have a potent anti-depressive effect within minutes, long before neurogenetic responses have even started. For example, a depressed person rarely thinks and behaves like a depressed person while under the influence of MDMA or cocaine. This is perhaps one of the major reasons why depressed people are prone to substance abuse.

So, how do antidepressants work?

- Most antidepressants lead to a sudden increase in the levels of certain neurotransmitters, which has some effects on its own. For example, when I take moclobemide, I feel a significant uplift already after a couple of hours.

- Antidepressants also lead to a more gradual change in gene expression and network-level adaptation in a variety of brain networks, including but not limited to a boost in hippocampal neurogenesis.

- Over time, these neurobiochemical changes also influence a person’s thinking patterns and life situation, something that is, in my opinion, not commonly talked about when the “mechanism of action” of antidepressants is considered. I discuss this in more detail in The Power of Neurobiochemistry.

To the naysayers

I met a lot of people who are dead certain that the cause of depression is all about mindset, relationships, and purpose. I partially agree, but it is not that simple.

“Mindset is what it is all about!” Well, if my energy and mood are always crap, so will my “mindset”, thinking patterns, and outlooks on life.

“Relationships are what it is all about!” Well, if I am chronically lethargic, anxious, or unmotivated, I do not want to interact with others in the first place. Plus, others will not want to interact with me.

“Purpose and meaning are what it is all about!” Well, if I feel like shit, I am much less likely to have zest for life, let alone dream.

“But there is evidence that depression is not a chemical imbalance!” Well, that piece of evidence was misrepresented by the mostly sensationalist and scientifically illiterate media. What the original study meant was that it is not as simple as low serotonin = depression. Rather, depression is an extraordinarily complex issue, which, on the biological side, involves neurotransmitter malfunction, nervous tissue inflammation, and dysregulated neurogenesis (all of which though are technically “chemical imbalances”).

A case for antidepressants

Biology is far from the whole picture and depressed individuals are often just human beings with unmet needs. The “biological malfunction” is often (but not always) a physiological signal that there is something wrong or missing.

By treating depression purely from a biological perspective, psychiatry disregards two fundamental human needs (connection and purpose) and therefore insinuates that the pain does not “mean” anything but is exclusively due to a “chemical imbalance”. While this may sometimes be the case, more often than not, this is overly simplistic.

Nonetheless, treating the “biological malfunction” can help people to start taking action and make life changes, which is often needed to treat depression effectively (and more importantly, sustainably).

A decade ago, I was low-level depressed. For some time, I was quite certain that my feelings were all about the story I told myself. However, after experimenting with hormones and antidepressants, I found that the story I tell myself can change shockingly quickly.

“Nothing is good or bad but thinking makes it so.” It is the mind that translates outer conditions into happiness or suffering. But if this translator does not work well, I will be much less likely to become content. The configuration of this translator relies heavily on the levels of monoamines and other neurotransmitters, which can in theory (and to a lesser extent in practice) be manipulated like the settings on a graphic equalizer.

If my neurochemistry gets “better”, this changes my mood and thinking patterns, which then indirectly also changes not just my outlook on the world and life, but most importantly my real life itself.

Getting my neurobiochemistry in order helped me a great deal with “solving” existential problems.

This is not to say that periods of self-doubt, questioning, despair, and unhappiness were not useful – they often were. For me, these periods were quite formative. However, in my opinion, these periods should be short. As a friend of mine likes to say, they are just like inflammation. Acute inflammation is healing but chronic inflammation is destructive.

Regardless of etiology, depressed people (or people who subjectively suffer) are more prone to obesity, smoking, and substance abuse, and have a 15–30-year shorter life expectancy on average. In addition, depression is known to have adverse effects on pretty much every aspect of cognition and long-term brain health.

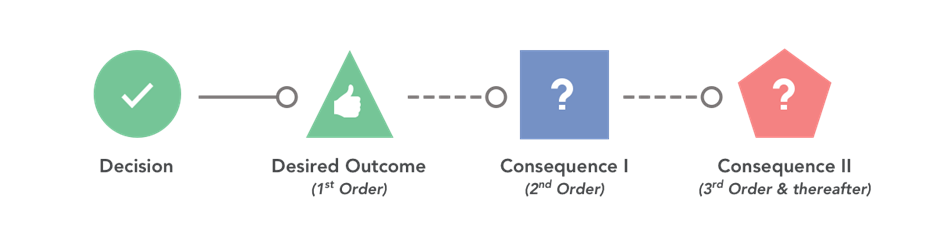

Most worryingly, serious depression may also wreak havoc on someone’s future life. People might fall out with their partner, they might be laid off from work, they might develop a substance addiction – and the 2nd and 3rd order consequences of these events may persist for many years to come, long after the depression is over.

Furthermore, depression is arguably not just bad for the person affected, but also for society, because the way people act or do not act affects many other people as well, either directly or indirectly. Moreover, depressed people contribute less to society compared to what they could (instead, they often use up society’s resources).

Because of these huge indirect costs associated with the condition, depression is thought to be one of the costliest disorders.

While lifestyle choices and psychotherapy are great and should be tried first, antidepressants certainly have their rightful place, and their risks and side effects need to be weighed against the risks and side effects of depression. (I discuss this in more detail here: What Kind of Antidepressant Should I Choose?)

Some people assume that antidepressants are bad for the brain. However, so is depression. Not only is depression a subjectively nasty state to be in, but it is an objectively unhealthy brain state to be in because:

- Firstly, the biochemical nature of depression has direct adverse effects on brain health (e.g., high levels of cortisol, neuroinflammation, low monoamine levels).

- Secondly, depressed people are less likely to lead a healthy lifestyle (e.g., sleep, exercise, diet, socializing, etc.), which has a host of indirect adverse effects on brain health.

- Thirdly, the use of antidepressants may protect users against using other “dirtier” chemical shortcuts for pleasure and escape (e.g., highly palatable foods, weed, alcohol, opioids, etc.), therefore being “the lesser evil”.

Are antidepressants alone sufficient?

Let’s make an analogy with high blood pressure. To effectively treat hypertension, most people need both lifestyle changes as well as medication. Either one of the two is only partially effective. However, combined they are synergizing.

Similar things hold true for depression. Meds + lifestyle + psychotherapy is more effective (and sustainable) than either alone. After lifestyle changes are well established and new thinking patterns have taken hold, medication can often be reduced and even weaned completely (unless there are strong genetic factors).

However, similarly to hypertension, treatment should start rather early, as otherwise damage will be done. In the case of hypertension, the damage will be done to the eyes, kidneys, and heart, while in the case of depression, the damage will be done to one’s life situation. Much of the damage can stick around for a long time, sometimes for life, even after hypertension or depression have been treated.

Different analogy. The treatment of depression with antidepressants can be compared to building muscle with the use of steroids: Although steroids by themselves will cause an automatic change in muscle growth (the same way antidepressants directly affect brain wiring), if not combined with a proper exercise and nutrition regime (i.e., conscious effort), the user will not get very far.

Conversely, if steroids are combined with proper exercise and diet, gains are synergistic. Even if the user then stopped taking the steroids, just maintaining the muscle that has been built is much easier than building it in the first place (which would not have been possible to such an extent without the use of steroids). His physique will show signs for a long time.

Analogously, even if someone stopped antidepressant treatment, due to combined changes in brain wiring, thinking patterns, habits, and life circumstances, at least some of the effects will (likely) persist, especially if mental and behavioral habits are maintained by deliberate effort.

Sources & further reading

- Website: Wikipedia – Biology of Depression

- Anecdotes: Reddit – r/depressionregimens

- Website: (Useful) List of investigational antidepressants

Disclaimer

The content available on this website is based on the author’s individual research, opinions, and personal experiences. It is intended solely for informational and entertainment purposes and does not constitute medical advice. The author does not endorse the use of supplements, pharmaceutical drugs, or hormones without the direct oversight of a qualified physician. People should never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something they have read on the internet.