While dopamine may be overhyped by the public, it is very neglected by current psychiatric regimens, hence the title.

Dopamine is important

As I was on moclobemide (a reversible inhibitor of MAO-A – elevating serotonin levels relative to dopamine levels), increasing from 150mg to 300mg worsened my energy levels. Furthermore, I felt dumber, less confident, my brain was slower, and I had less “personality” (more flat, listless, somewhat anhedonic, less sharp, and witty). I also had less fire or zest in me, and life felt somewhat colorless. The addition of a very low dose of rasagiline (an irreversible MAO-B inhibitor – specifically elevating dopamine levels) abolished all of this already on day one.

There seems to be a specific pattern of depressive symptoms that is inadequately addressed by serotonergic antidepressants. Among these symptoms are anhedonia, reduced motivation, loss of interest, fatigue, and apathy.

These “anergic” or “atypical” features of depression are thought to be at least in part due to a relative dopamine deficiency. Unfortunately, conventional antidepressant treatment regimens barbarically neglect the crucial role of dopamine but mainly focus on serotonin and to a lesser degree noradrenaline. This is unfortunate for amotivational and listless types of depression, which are by no means rare.

Treating these patients with SSRIs often exacerbates the issue, causing a state of so-called “amotivational syndrome”, perhaps in part because (excess) serotonin further suppresses dopamine signaling due to serotonin-mediated modulation of VTA neurons (midbrain dopamine neurons).

As described in An Introduction to Neurotransmitters, no matter how much one believes in the importance of psychological factors, dopamine levels are among the primary determinants behind how motivated one is and how ready one is to push through things to get what one wants.

Besides incentive salience (a fancy word for motivation), dopamine is also thought to be important for concentration, zest for life, and the ability to experience pleasure. The philosopher David Pearce argues that dopamine increases the range of activities an animal finds worthwhile pursuing.

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

And since most antidepressant treatments do not directly enhance DA neurotransmission, this possibly contributes to “residual symptoms”, including impaired motivation, brain fog, and anhedonia. For many people, these symptoms tend to get somewhat better by either switching to a more dopaminergic drug (e.g., from escitalopram to bupropion) or augmenting with one.

The anti-depressive effects of dopamine are twofold.

- Firstly, high dopamine itself “feels good”. Anyone who has ever taken the selective DAT-inhibitor modafinil can probably attest to this.

- Secondly, and more importantly, dopamine increases drive and motivation, which enables people to get up from the coach and improve their life circumstances and themselves. This does not just “feel good” but also has tangible effects in real life, with important bidirectional feedback loops on the psyche.

As psychiatrist Ken Gilman points out, the long-standing neglect of dopamine’s role in depression is reflected in the fact that none of the frequently used dopamine reuptake inhibitors such as methylphenidate, amphetamine, modafinil were ever classified as antidepressants (except for the poorly known amineptine). Both modafinil and methylphenidate are actually quite effective antidepressants by themselves.

It seems that things are slowly beginning to change, and more and more psychiatrists are starting to use these drugs as augmentation agents and sometimes even as stand-alone treatments.

Sadly, the way modern psychiatry treats depression resembles a strategy to relieve misery instead of promoting well-being. What is lacking from the antidepressant arsenal is a wider range of molecules that enhance dopaminergic signaling.

Unfortunately, the erroneously dubbed “feel-good” transmitter is still mostly off-limits, which though is understandable as it carries a non-theoretical risk of causing addiction, which may be even higher in already depressed individuals.

Hopefully, as research progresses (and dogmas abate), psychiatry will eventually be capable of delivering high-functioning and socially responsible well-being. Not brutally neglecting dopamine is probably part of the equation.

The science of dopamine

It is an absolute myth that dopamine causes “pleasure”. The myth exists because most drugs of abuse get their addictive properties from dopamine release. While this is true, dopamine has little to do with pleasure but rather the mesolimbic dopamine system mediates reward signaling, incentive salience, and a sense of urgency and importance, and not pure bliss (opioidergic).

Dopamine is critical to approach behaviors of all kinds and to the capacity to switch from one behavior to another. Dopamine is one of the primary (biological) determinants behind motivation and excitement – how much effort one is willing to put in to get to a desired goal.

There is a widespread misconception that dopamine is the “pleasure neurotransmitter”. It is not. Instead, dopamine has mostly to do with incentive salience (a fancy term for “motivation”).

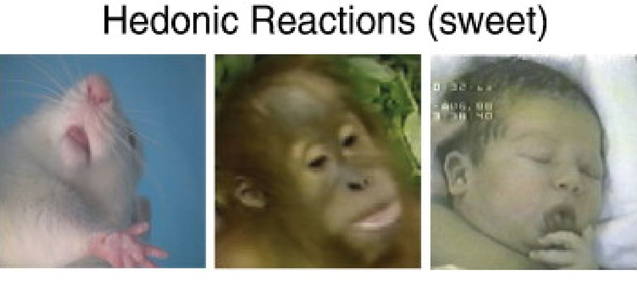

In scientific terms, incentive salience is called “wanting”, whereas pleasure is called “liking”. Pleasure (“liking”) is mostly mediated by opioidergic pathways in the nucleus accumbens shell. Opioid systems are discussed in more detail here.

The vertebrate reward system 101

The “wanting” + “liking” pathways form the endogenous reward system. To simplify, the release of dopamine initially regulates the “wanting” sensation (e.g., desiring chocolate). Upon fulfilling the desired target (e.g., consuming chocolate), endorphins (which are naturally occurring opiates) then induce the “liking” sensation.

Example. If one experimentally blocks dopamine in rats, they starve to death because they would not do any work to get to the food. However, if food is put into their mouth, their pleasure reaction is unchanged (as measured by orofacial muscle activation).

Conversely, if one blocks opioidergic pathways, they will still work to acquire food, but they do not “like” eating it.

Dopamine signaling

There are five different dopamine receptors (D1- D5) coupled to two different functional intracellular signaling pathways, Gs and Gi. In general, dopamine release activates a certain set of brain networks implicated in motivation, cognition, and motor behavior.

It does so either directly by being coupled to neurons expressing Gs-coupled pathways (“Dear cell, please do more of what you are already doing.”), or it does so by activating Gi-coupled pathways on inhibitory interneurons (“Dear cell, please do less of what you are already doing.”).

In the latter case, dopamine signaling then functions as an “off-switch” to these inhibitory interneurons, leading to disinhibition, which in the process upregulates the net output of a certain network. The famous D2 receptor is of this type, the major target of antipsychotic drugs.

At its core, dopamine works similarly to noradrenaline. Namely, increasing or decreasing the activity of certain neural networks. However, while noradrenaline is distributed to the whole brain and spinal cord, dopamine is much more selective in its targets.

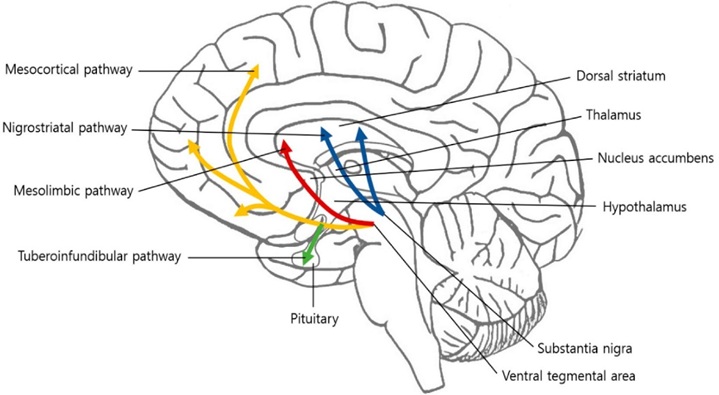

There are four major dopamine pathways.

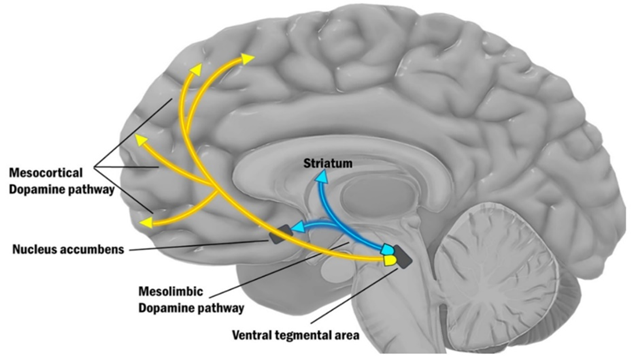

- The mesolimbic pathway (“motivation”): As the name implies, the mesolimbic pathway projects from the midbrain (“meso”) to the limbic system (“limbic”), more specifically the nucleus accumbens. The mesolimbic pathway is important for regulating motivation and approach behavior (“wanting”). This pathway is part of the reward system, as explained above.

- The mesocortical pathway (“cognition”): This pathway projects from the midbrain (“meso”) to the prefrontal cortices (“cortical”). The mesocortical pathway is important for regulating focus & cognition. In this pathway, expression of the dopamine transporter (DAT) is low, and most of the dopamine reuptake is carried out by the noradrenaline transporter NET. For this reason, noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors such as reboxetine are a viable treatment for ADHD because they increase domain levels in the prefrontal cortex. I share my thoughts on ADHD here: ADHD – To Treat Or Not to Treat?

- The nigrostriatal pathway (“movement”): In this pathway, dopamine projects from the substantia nigra (SN) to the dorsal striatum. The nigro-striatal pathway is important for regulating motor behavior (movement). This pathway is most famous for being dysfunctional in Parkinson’s disease (though in reality, the other dopamine pathways are just as dysfunctional).

- The tuberoinfundibular pathway (“prolactin”): In this pathway, dopamine controls the release of prolactin. Therefore, dopamine agonists are clinically used to treat high prolactin levels.

For our purposes, we only care about the first two pathways, the mesolimbic pathway (shown above as the red arrow) and the mesocortical (yellow arrows).

The mesolimbic pathway is important for motivation.

In the mesolimbic pathway, a collection of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) projects to the nucleus accumbens, which is the entry point into the limbic loop of the basal ganglia system.

The mesolimbic dopamine system mediates incentive salience (motivation), which is critical to vitality, curiosity, agency, libido, an ability to anticipate reward (to look forward to things), and a sense of urgency and importance.

Hyperdopaminergic states tend to increase the range of activities an organism finds worthwhile pursuing. Conversely, hypodopaminergic states result in anhedonia, loss of motivation, and a lack of perceived meaning in one’s life experience.

This pathway is thought to be dysfunctional in ADHD, some forms of depression, and anhedonia.

There are a variety of things that are thought to decrease dopamine levels in this pathway. Important among these are obesity, low testosterone, low cortisol, some kinds of depression, and any form of addiction.

Most stimulants temporarily increase activity in the mesolimbic pathway, and therefore they tend to increase one’s motivation to act. However, they are rarely viable long-term solutions (as discussed here).

The mesocortical pathway is important for focus and cognition.

In this pathway, a collection of dopamine neurons in the VTA projects to various key populations of neurons in the frontal cortices, amygdalae, anterior cingulate cortices, and hippocampi. There, dopamine upregulates pathways that improve focus (the narrowing of attention) and cognition (executive functions), which is useful for helping with goal-directed behavior (e.g., planning).

Usually, the mesolimbic and the mesocortical pathways operate together. That is, dopamine release in these two pathways happens at the same time.

- The mesolimbic pathway mediates the “wanting” to do something specific. For example, “I want to eat chocolate”.

- Meanwhile, dopamine released through the mesocortical pathway activates brain networks associated with executive functions, such as improving focus and sharpening working memory. These improvements in cognition then help with attaining the target of the “wanting” (i.e., cognition is harnessed to execute the correct behaviors to obtain the chocolate).

Therefore, whenever dopamine levels rise, motivation (mesolimbic pathway) and cognition (mesocortical pathway) increase at the same time. In fact, dopaminergic stimulants do not only improve motivation to act, but they also improve mental performance – at least temporarily. This effect is particularly pronounced with working memory.

Interestingly, dopamine transporter (DAT) expression is low in the prefrontal cortices, and most of the dopamine reuptake in the mesocortical pathway happens via the noradrenaline transporter (NET). Therefore, noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, such as reboxetine, improve dopamine transmission selectively in the mesocortical system.

Dopamine, personality, and aging

As I was using selegiline, a selective MAO-B inhibitor elevating dopamine levels, I found that it made me more restless, impulsive, curious, and agentic. While I was incredibly productive on it and made quite a bit of money, I also found that it changed my personality in not-so-favorable ways. I discuss my experience with selegiline in more detail here.

As mentioned in the section on guiding principles, biological factors ripple through someone’s life in the same way an Earthquake ripples through the Earth’s crust.

Different dopamine receptor polymorphisms are correlated with certain aspects of human personality. For example, a specific genotype of the dopamine D4 receptor is correlated to the personality trait of “novelty-seeking”, which is characterized by exploration, risk-taking, curiosity, and impulsiveness.

Furthermore, personality changes with aging. While there are many reasons, I believe that a reduction in dopaminergic tone is not to be neglected.

Compared to adults, children appear hypomanic at baseline. They are emotional, have great energy, are curious, and act impulsively. This is thought to be in part due to their high dopaminergic tone. As they get older, they get less curious and enthusiastic. Most people assume this to be due to them being tortured by archaic education systems, but it is not just nurture but also nature – in fact, dopamine levels progressively decline with aging.

In fact, of the about 85 billion or so neurons, only a mere 400-500 thousand neurons manufacture dopamine (the actual count varies between individuals), and approximately 5-10% of these neurons are lost per decade.

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

Furthermore, testosterone and cortisol levels also decrease with aging, which are two hormones that significantly regulate dopaminergic tone.

I believe that next to Groundhog Day setting in, this progressive reduction in dopaminergic drive is part of the reason people who were once brimming with energy, ambition, and a sense of purpose in their twenties, often transition from productive go-getters to couch potatoes.

Molecules targeting the dopamine system

So, should everybody simply get on amphetamines? In my opinion, amphetamines should only be used temporarily (if at all), simply because most people tend to be worse off after stopping them. While they are great for treating a lack of volition and related symptoms, the withdrawal is horrible, and the anhedonia and apathy come back with a vengeance. Furthermore, they may have deleterious effects on long-term brain health, much more so than other dopaminergic agents.

Less potent (but more sustainable) substitutes are bupropion, modafinil, and methylphenidate. Low doses of rasagiline or selegiline are also an option. For more severe cases, there is always tranylcypromine. Other dopamine modulators are caffeine and nicotine – it is surely no coincidence that psychiatric patients are frequently consuming both in large quantities.

Another option that is becoming more and more popular is testosterone replacement for males (and sometimes females). These effects on the dopamine system are among the primary reasons why so many males are psychologically addicted to anabolic steroids. Androgen receptors are highly prevalent in the mesolimbic reward system, elevating dopamine levels. Similarly, 5-alpha reductase inhibitors such as finasteride reduce dopamine levels and are associated with anxiety, “brain fog”, and depression (though their effect on neurosteroids might also play a role).

Another poorly known strategy is the addition of dopamine agonists, such as pramipexole. Pramipexole is a D2-agonist intended for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Because it directly activates dopaminergic pathways, pramipexole may be a promising treatment for severe cases of anhedonia and treatment-resistant depression, though more research is needed on long-term safety. However, reportedly, it can cause people to become slaves to their vices (e.g., gambling, porn, food, drugs). Weirdly, it also causes tiredness.

Low doses of atypical antipsychotics such as cariprazine, amisulpride, and aripiprazole may also amplify dopamine signaling.

Two “conventional” antidepressants that have an appreciable affinity for the dopamine transporter (DAT) are bupropion (at conventional doses a DAT-occupancy of roughly 20%) and sertraline. While bupropion is classified as a noradrenaline-dopamine-reuptake inhibitor (NDRI), sertraline is wrongly classified (based on pharmacological affinities) as an SSRI – it has more rights to being classified as an “SDRI” compared to venlafaxine as an “SNRI”. SSRIs are discussed in more detail here: Thoughts on SSRIs

In my opinion, both bupropion and sertraline are suitable first-line antidepressants for depressed individuals with little motivation.

The triple reuptake inhibitors (inhibiting SERT, NET, DAT) ansofaxine and dasotraline are currently in Phase III and, if things go well, both will be available for clinical use in the not-so-distant future. I discuss both of these molecules here: “Noteworthy Molecules in Pharmaceutical Pipelines”.

For the light-hearted individuals (or for individuals who do not have access to prescription drugs) there is S-adenosyl-methionine, an over-the-counter supplement that appreciably increases dopamine levels (at least at the beginning of treatment until cruel counterregulatory measures are set in motion).

My experience with increasing my dopamine levels: upsides & downsides

(Background: Rasagiline is an irreversible MAO-B inhibitor. As such, it inhibits the breakdown of dopamine and trace amines. Rasagiline and selegiline are the only drugs currently available that increase dopamine in a “natural” way – they inhibit breakdown and thus dopamine content of presynaptic vesicles simply becomes larger. It elevates dopamine in a very different way compared to reuptake inhibitors (such as modafinil) or release-inducers (such as amphetamine). It also “feels” quite different. A single dose has subtle effects on the order of weeks due to the slow turnover of MAO-B.)

Whenever I add microdoses of rasagiline to my stack, quite soon (hours) I notice a couple of subtle and not so subtle changes.

During the first couple of days, there is a low-grade euphoria and generally an increased feeling of “I love life” and purpose. However, these go back to baseline after a couple of days, even with continued dosing. This is very similar to the honeymoon phase of testosterone replacement therapy, which is also due to temporary “dopamine supersensitivity”.

Whenever I add rasagiline, I notice that I become more impulsive. I generally try to open WhatsApp only every couple of hours but on rasagiline, I sometimes open it “without even thinking” many times per day. It seems that mindfulness decreases and the gap between “stimulus and response” becomes smaller. This is in line with what we know about dopamine. A friend says, that on rasagiline he procrastinates all day because he is just so impulsive and constantly goes down rabbit holes. (Conversely, another friend claims that on rasagiline he procrastinates less because he finally has the willpower and agency to just commence working.)

Dopamine generally increases the range of activities an animal finds worthwhile pursuing and I definitely notice that. When my dopamine is higher, it seems that I am generally more curious and interested in things.

I also become a little “anti-chill”. I find pleasure in working all the time and relaxing becomes hard and chore-like. I am naturally this way but on rasagiline it becomes too much. I need to be constantly “doing” something.

My ex-girlfriend usually noticed on day one when I started taking even a microdose of rasagiline (She was aware of what I was taking and why – she is a doctor). She is quite perceptive and on rasagiline my behavior is nudged towards a specific direction, which she picked up on without fail. On rasagiline, I am also a little more prone to wanting to have things go “my way”. I am also a tad more of an asshole due to the combination of impulsivity, impatience, and reduced cooperativeness. Rasagiline was definitely not good for my relationship.

My mood seems to subtly improve on it (a lot during the first few weeks, from then on much less but probably still above baseline).

On rasagiline, I also seem to be less prudent (e.g., my threshold for engaging in new experiments becomes much lower).

On it, my thinking is rushed and almost becomes ADHD-like (which is not necessarily bad). I “jump” quite a bit and sometimes in conversations I can make unexpected subject changes, due to my brain becoming “faster”.

On it, I am also slightly more emotional and moved to tears more often.

After experimenting with different dosage ranges, I settled on a very low dose – 0.025mg per day (standard dose is 1mg per day), which means that I take 1 tablet in a span of 40 days. I tried higher doses but that did not go too well. It is always fascinating how powerful rasagiline is. I do think it is more powerful for me than many other people because my dopaminergic tone seems to be quite high already.

If it were not for rasagiline, I may have not started these Weekly Observations (which I started back in February three days after restarting rasagiline after a long hiatus from the molecule). After starting rasagiline, I also wrote a dozen new article drafts within the span of a couple of weeks (none of them have been published on Desmolysium thus far).

I am currently off rasagiline because overall it seems that the risks of the drug (mostly stemming from the increase in impulsivity and decrease in prudence) and the effects it has on my relationships (e.g., less cooperativeness) are not worth the gain in speed. If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together. Rasagiline only helps with going fast but may actually reduce my chances of going far.

However, I am positive that I will use it again (e.g., during work sabbaticals) from time to time in the future, just not as a fixed part of my stack.

Generally, most people assume that having more dopamine is better. Every single person I know that has tried rasagiline has eventually come off it. Some still use it during short periods only. If “more dopamine was better”, I am sure that at least one person would have included it as a fixed part of their regimen. Of note, at these dosages, rasagiline has pretty much no side effects other than the unwanted effects of increased dopamine itself.

What some of my friends noticed:

- More fuzzy thinking; constant thought-jumps

- Increased tendency to procrastinate (some noticed a decreased tendency to procrastinate). On rasagiline, it is much easier to “start doing”…but it is also much easier to give in to impulses, which for some people can have net detrimental effects on productivity.

- Greater agency (e.g., “On rasagiline, I always complete my daily to-do list.”)

- Increased tendency to give in to urges (e.g., nicotine, porn, sweets, buying lottery tickets)

- Increased sense of purpose

- Greater curiosity and creativity

- Wanting to break up with current partner

- More frequent thoughts about sex; increase in libido; urge to be more promiscuous

- Increase in aggressive and violent thoughts

- Being more dominant in social situations

- Being more eloquent

Related articles

Sources & further information

- Scientific review: Dopamine System Dysregulation in Major Depressive Disorders

- Scientific review: Neurobiological mechanisms of anhedonia

- Website: Psychotropical – Dopamine and Depression

Disclaimer

The content on this website represents the opinion and personal experience of the author and does not constitute medical advice. The author does not endorse the use of supplements, pharmaceutical drugs, or hormones without a doctor’s supervision. The content presented is exclusively for informational and entertainment purposes. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on the internet.