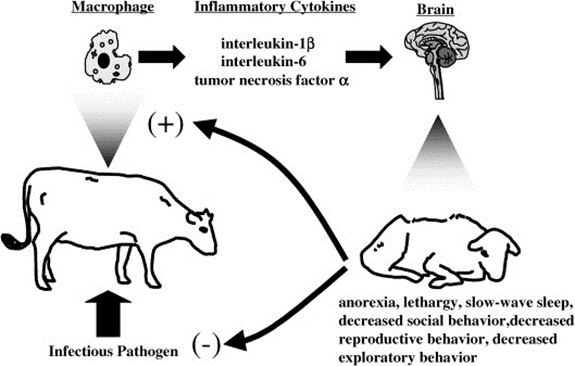

Certain subtypes of lethargy or depression are due to sickness behavior. “Sickness behavior” refers to a set of behavioral and mental changes that occur in response to an infection or inflammation.

Sickness behavior is characterized by a range of symptoms, including brain fog, fatigue, lethargy, anhedonia, a desire to withdraw, and altered sleep and appetite. These changes are thought to be an evolutionary adaptation that enables the body to conserve energy and focus on fighting infection or inflammation. Furthermore, it is thought that “sickness behavior” also induces a withdrawal from group living, which would help the group as well as prevent ostracization of the individual.

Infections occur more or less frequently in everybody, depending on the strength of one’s immune system and exposure to viral pathogens. Many of these infections are too minor to manifest in true “sickness” (and may therefore go unnoticed) but large enough to decrease vitality in more than subtle ways.

Therefore, certain instances of unexplainable drops in energy levels, mood, motivation, and cognition, are due to (unrecognized) inflammation. Potent cytokinemia is a multiplier-by-0 (x*0 = 0) for good energy levels and mood, and stimulants are inadequate to address this.

Personal experience

Sometimes, when I have an unexplained drop in energy and mood, taking a low dose of dexibuprofen works wonders.

Example: On day X, I feel like crap. I take caffeine or modafinil, but I still feel like crap. If I then take a single dose of 200mg dexibuprofen, sometimes the fatigue, brain fog, and anhedonia are quickly abolished. Essentially having the effects that people aim to get by using stimulants.

I use dexibuprofen (the r-isomer) instead of racemic ibuprofen because the L-isomer seems to be mostly useless and thus unnecessary workload for the liver and kidney.

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

How it works

During an infection, cytokine levels increase. Cytokines are a group of proteins that link immune activation to the rest of the body. Next to having effects on all major organ systems, they also have effects on the central nervous system, where they act on many brain sites, including the vagus nerve, brain stem, hypothalamic sites, and monoamine-producing neurons.

Among many other things, increased brain cytokine signaling results in a decrease in hypothalamic arousal activity (histamine & orexin levels decrease), an increase in HPA-axis activity (cortisol levels), and a damping of monoaminergic transmission (dopamine, serotonin, noradrenaline).

Together, this manifests as “sickness behavior” characterized by lethargy, withdrawal, apathy, low mood, and brain fog. These symptoms are similar to those seen in depression, and it is thought that a subgroup of depression has a causal link to an immunological component. It is no coincidence that many of the genes having the strongest associations with depression are immune-related genes.

Ibuprofen is a COX inhibitor, which results in the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis, among other effects. Prostaglandins participate in tissue housekeeping functions throughout the body. However, prostaglandins are also employed as mediators of inflammatory signals, signaling “hey, there is inflammation going on” to nerve endings, monoaminergic nuclei, and hypothalamic control centers, among others.

By inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis, certain brain sites are prevented from entering “sickness mode”. This results in an anti-“feeling-like-shit” effect, anti-cognition dampening effects, and anti-brain-fog effects.

Acetylsalicylic acid (Aspirin) is useful as well, though its effects are not particularly long-lasting, and it also promotes bleeding due to its disproportionate effects on thrombocytes (platelets). Furthermore, compared to ibuprofen, acetylsalicylic acid is less specific for COX-II, the major COX isozyme induced by inflammation. Paracetamol is mostly ineffective in this regard as its COX-inhibiting properties are low – we still do not know how exactly it works.

Data on celecoxib (a selective COX-II inhibitor) in depression have been promising, particularly if CRP levels are above 0.3mg/dl.

Warning

Inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis also prevents the formation of prostaglandin for housekeeping functions such as the production of stomach glycoproteins, regulation of blood flow through the kidneys, vasomodulation, prevention of clotting, and melatonin synthesis, among others.

Therefore, COX-inhibiting drugs should only be taken occasionally. Furthermore, if minor infections occur more often than “normal”, other potential underlying health issues should be ruled out, such as hypothyroidism, anatomically abnormal sinuses, or hematological disorders.

In the case of chronic low-level inflammation (e.g., autoimmune issues, obesity), COX inhibitors are useful but carry significant long-term risks, including an uptick in cardiovascular mortality. In these cases, it is worth looking at low-dose naltrexone, rapamycin, or getting properly checked out by a rheumatologist and/or allergologist.

Other experience reports

For a discussion of the molecular correlates of well-being, and links to accounts of various related molecules I have experimented with, read here.

For a full list of experience reports click here.

Sources & further information

- Scientific review: Depression and sickness behavior are Janus-faced responses to shared inflammatory pathways

- Scientific review: Anti-inflammatory treatment for major depressive disorder: implications for patients with an elevated immune profile and non-responders to standard antidepressant therapy

- Scientific review: Immunological Mechanisms of Sickness Behavior in Viral Infection

Disclaimer

The content available on this website is based on the author’s individual research, opinions, and personal experiences. It is intended solely for informational and entertainment purposes and does not constitute medical advice. The author does not endorse the use of supplements, pharmaceutical drugs, or hormones without the direct oversight of a qualified physician. People should never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something they have read on the internet.