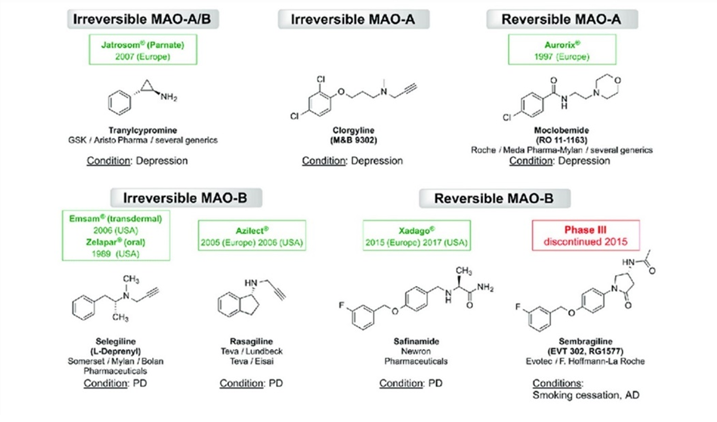

I discuss moclobemide (a reversible MAO inhibitor) and the science of MAO inhibition here. In this article, I only share a couple of thoughts on irreversible MAOIs.

Irreversible MAO inhibitors such as tranylcypromine (an amphetamine derivative) and phenelzine are among the most powerful antidepressants known to mankind (also known as “nuclear” antidepressants) and they are one of the few antidepressants that have potent mood-elevating effects even in non-depressed people, often inducing hypomania-like behavior.

While irreversible MAOIs have risks, the risks of untreated/poorly treated mood disorders far surpasses any potential risk of MAOIs. Many people have lost half their life trying every treatment available (legal and otherwise) due to depression. Regardless of the increased health-risks from depression, well-being on a daily basis itself is valuable and many would gladly accept a reduction in life expectancy for life to be less miserable.

As a quick piece of info, “irreversible” does not mean lifetime-irreversible but rather irreversible in the sense that inhibition renders the enzyme useless. However, MAO enzymes have a natural turnover time of about 2-3 weeks, and thereafter, MAO levels will be back to baseline if one stops taking the inhibitor. So, “irreversible” MAO inhibitors inhibit MAO-enzymes irreversibly for only a couple of weeks.

Two friends of mine have experimented with literally every antidepressant under the sun, and low doses of irreversible MAO inhibitors were the only thing that, according to them, really helped their depression. One of them was talking the ears off of everyone when he first started. Both use much lower than “therapeutic” doses (e.g., 2.5-10mg of tranylcypromine instead of 60mg).

As Dr. Gilman says: “MAOIs are not riskier than being ill with unresolved, or incompletely treated depression, because, not only is the life-time risk of death by suicide around 10%, but also the Standardised Mortality Ratio SMR (which includes death from other causes than suicide) is as much as 10-30 times elevated.”

The use of MAOIs has been declining sharply over the last couple of decades, in part because of a lack of industry support (the patent expired decades ago), and in part because of the life-threatening reactions these drugs tend to cause. While some of the fear is surely overblown, some of it is surely warranted.

They carry two major risks: serotonin syndrome (if combined with serotonergic molecules) and a hypertensive crisis (if combined with the wrong foods or stimulants). In fact, one of my friends had three closed-angle glaucoma attacks within the first two months of starting therapy, likely caused by not paying sufficient attention to dietary tyramine. Because keeping his eyesight is important to him, he had to stop.

Irreversible MAO inhibitors have a lot more side effects than the “gentle” moclobemide, the most troublesome of which are insomnia, debilitating hypotension, and fatigue.

If irreversible MAO inhibitors elevate all major monoamines, why then do they result in fatigue? People on moclobemide rarely report fatigue, and neither do people on MAO-B inhibitors. Therefore, irreversible inhibition of MAO-A is the most likely culprit.

While there are many theories, the only one I find plausible is that the fatigue is related to the accumulation of octopamine from the improper metabolism of noradrenaline due to the irreversible inhibition of MAO-A. Octopamine is considered a “false” transmitter, incapable of activating noradrenergic alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptors.

As octopamine accumulates, it takes the place of noradrenaline in synaptic vesicles. It gets released when noradrenaline is supposed to be and is incapable of activating adrenergic receptors, resulting in functional suppression of adrenergic activity all over the nervous system.

Irreversible MAO-inhibitors are essentially having a sympatholytic action, and the body-wide decline in noradrenaline signaling leads to an inability to vasoconstrict properly, resulting in severe orthostatic dysfunction and hypotension. In fact, in the beginning of treatment, many people report that they nearly pass out frequently.

Furthermore, the sharp drop in brain noradrenaline levels results in fatigue.

While irreversible MAOIs can bring about spectacular remission of depression in treatment-resistant cases, they come with great side effects (low blood pressure, fatigue, insomnia) and a real and substantial risk of experiencing a hypertensive crisis or a serotonin syndrome at least once during the course of treatment, both of which can be deadly.

Irreversible MAOIs are perhaps the hardest antidepressants to start (e.g., debilitating hypotension, insomnia, the necessity to avoid tyramine and a host of other drugs) and the hardest to stop (e.g., crippling anxiety, nightmares, paranoia, delusions). This is very different from moclobemide, which is easy to start and easy to stop.

Last but not least, irreversible MAO inhibitors tend to eliminate empathy – with potentially adverse effects not just on the life of the user, but possibly also on the people the user interacts with.

However, and most importantly,

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

Thoughts on combining MAO-inhibitors + stimulants

Some doctors like to prescribe stimulants to patients on irreversible MAO inhibitors to combat the hypotension and lethargy. Even though, if done cautiously, it may be safe in terms of blood pressure and acute toxicity, the synergistic elevation in monoamine levels from combined reuptake inhibition + inhibition of monoamine metabolism may pharmacologically replicate some neurodegenerative aspects of manic episodes, causing low-level chronic excitotoxicity, potentially resulting in early-onset dementia.

Even though there is currently no scientific evidence for this (the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence), there is plenty of evidence from animal studies and observations in human amphetamine abusers that high-dose amphetamine is excitotoxic causing widespread brain damage, as discussed in detail here: Are (Therapeutic) Amphetamines Neurotoxic?

An MAO-inhibitor + low-dose amphetamine may be quite the same, regardless of the neuroprotective effects of MAO-B inhibition.

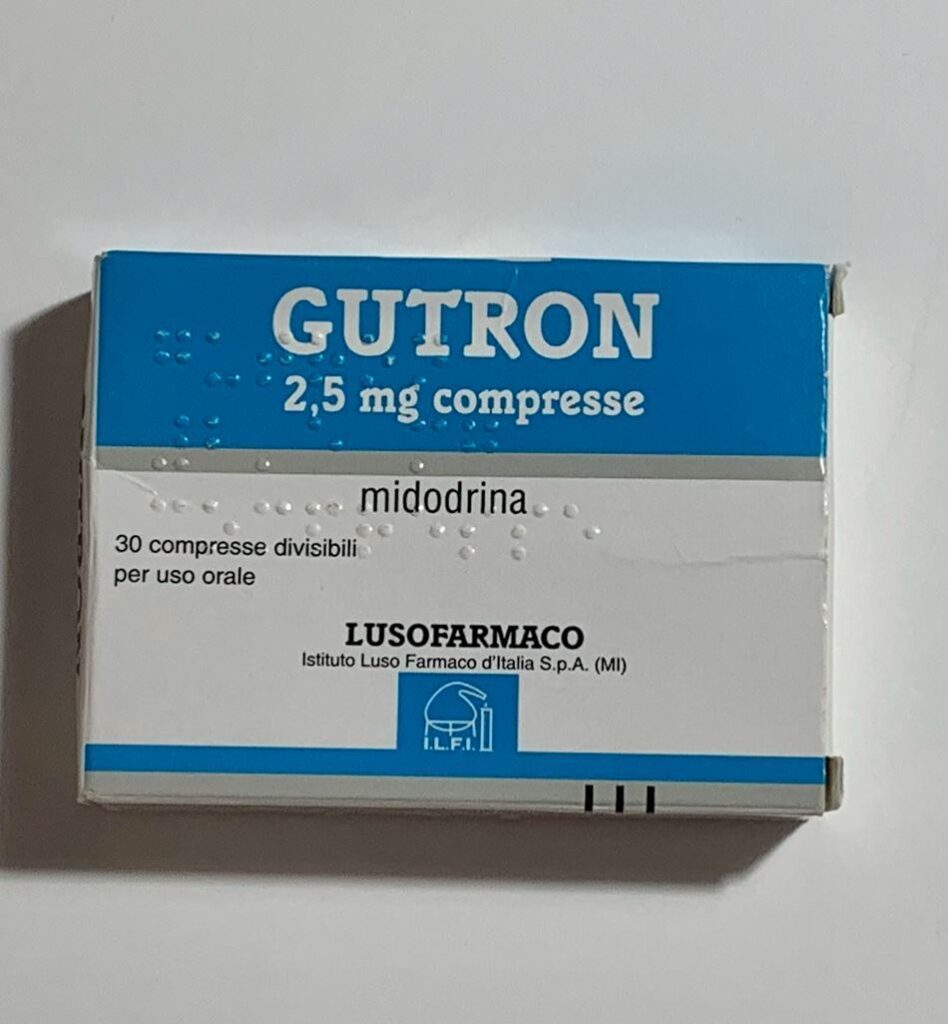

Instead of using the potentially neurotoxic combination of MAOIs + stimulants, one of my friends combated the MAOI-associated hypotension and fatigue by cycling the direct sympathomimetic drugs midodrine (an alpha-1 agonist) and low doses of clenbuterol (a beta-2 agonist).

If MAO-A is reversibly inhibited (e.g., moclobemide), octopamine will still be metabolized due to the on-off rate (reversibility) of the inhibitor at MAO-A. Therefore, RIMAs do not share the blood pressure-lowering effects of irreversible MAOIs, and they usually also do not have the fatigue associated with irreversible MAO inhibitors.

Similar things hold true for tyramine, which is a dopamine-noradrenaline-releasing agent present in some foods. Tyramine is normally eliminated by MAO-A or MAO-B in the gastrointestinal tract, but if both enzymes are inhibited irreversibly, this can cause tyramine to enter the circulatory system, and induce a release in catecholamines from sympathetic nerve endings resulting in a hypertensive crisis (severe increase in blood pressure), which often results in ER visits by MAOI patients.

For reversible MAO-A inhibitors (RIMAs), this is much less of a concern and mostly limited to bothersome but clinically insignificant hypertensive reactions. RIMAs also cause much less insomnia than irreversible MAO inhibitors.

MAO inhibitors are different.

Unfortunately, medicine is stuck with drugs that affect transmembrane signaling and the lion’s share of neuropharmaceutical interventions are based on it.

However, the key to bringing about true and lasting change is likely not the superficial transmembrane domain but rather the “deep” intracellular domain. Given that gene therapies are not yet available, currently, the only available intracellular interventions are hormones and MAO inhibitors (disregarding “mindset” and emotional work).

Regarding the latter, it is paradoxical that the only class of antidepressants that does not work on transmembrane receptors is also the oldest one. And regarding the former, I hope that psychiatry (and medicine in general) will someday recognize (and utilize) the power of hormones – even though they cannot be patented. Hormones are discussed in more detail here.

Other experience reports

For a discussion of the molecular correlates of well-being, and links to accounts of various related molecules I have experimented with, read here.

For a full list of experience reports click here.

Sources & further information

- Anecdotes: Reddit – r/MAOIs

- Scientific review: Moclobemide – An Update of its Pharmacological Properties and Therapeutic Use

- Website: Wikipedia – Moclobemide

Disclaimer

The content available on this website is based on the author’s individual research, opinions, and personal experiences. It is intended solely for informational and entertainment purposes and does not constitute medical advice. The author does not endorse the use of supplements, pharmaceutical drugs, or hormones without the direct oversight of a qualified physician. People should never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something they have read on the internet.