Amphetamines have been used for a long time and are widely regarded as safe. Anecdotal experience from a large number of people hints at the possibility that long-term amphetamine usage does “something” to the brain, and amphetamines are possibly more neurotoxic than they are made out to be by the average doctor.

That amphetamines are neurotoxicity was discovered a long time ago and the search term “amphetamine neurotoxicity” gives over 2600 results on PubMed. Unfortunately, articles also include methamphetamine (a slightly modified form of amphetamine) and methylenedioxy-methamphetamine aka MDMA.

This article is not about whether amphetamines are a good or a bad treatment choice for ADHD but rather about their potential long-term adverse effects on brain health.

Disclaimer

We know for certain that high-dose use of amphetamine is neurotoxic. However, the state of the research about whether the therapeutic use of amphetamines is neurotoxic or not is quite terrible, and it is hard to draw conclusions, in part because few have seriously investigated this. Research on monkeys, which are closely related to humans, seems to suggest that even therapeutic doses of amphetamines are indeed neurotoxic but squirrel monkeys are not humans. Unfortunately, scientific research in humans may be biased, confounded, or incompetently done. Furthermore, currently available technologies, are not very good at measuring microscopic brain damage.

As with everything else on this blog, everything discussed represents my personal opinion. Please do not make medical decisions based on the opinion of a random guy on the internet.

Evidence suggests that amphetamines are neurotoxic

The first few times people take amphetamines, many describe it as “life-changing”, especially if they have ADHD. Anecdotally, for some people, after coming off a couple of years later their minds are like ping pong balls and much worse than before. Some individuals experience persistent anhedonia, which improves only marginally over time, with reports of it lasting for years.

This condition might be partly attributed to individuals not recalling their pre-amphetamine life clearly. However, it is also plausible that this could be due to strong compensatory changes at the level of gene expression and structural changes in specific brain networks.

This may also be in part because of neurotoxicity. Part of the neurotoxicity may come from toxic dopamine metabolites produced by MAO-B, and part of it may be due to excitotoxicity. As the word suggests, excitotoxicity is cell death due to overstimulation, which increases intracellular calcium levels, which then activates caspase enzymes to initiate programmed cell death. In addition, there is a lot of data that amphetamines increase brain levels of oxidative stress.

However, few people are intellectually satisfied by anecdotal evidence or hypothetical speculation. There are also a few lines of “real” evidence hinting at the potential neurotoxicity of amphetamines:

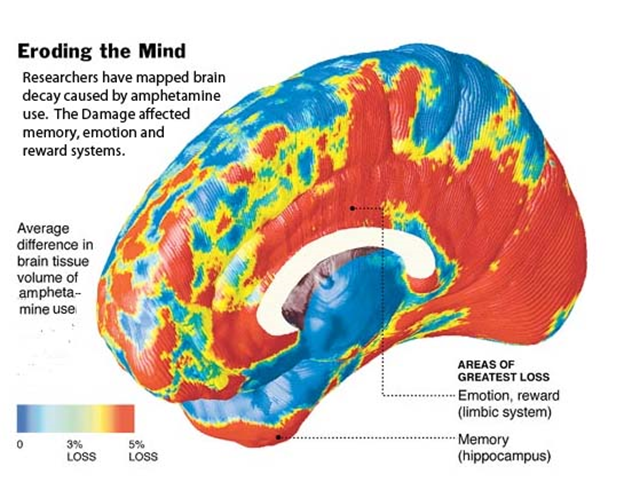

- It is known that the recreational use of amphetamines is (measurably) neurotoxic and leads to widespread neurotoxicity in the human brain, causing both white and grey matter atrophy in many regions. Methamphetamine and MDMA, both of which are amphetamines, are even more neurotoxic than the normal parent molecule.

- In animal models, high doses of amphetamine have been proven to be neurotoxic to dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurons in a similar way MDMA is neurotoxic to serotonergic neurons.

- Intense monoaminergic stimulation for prolonged periods of time, such as during manic episodes, is known to be neurodegenerative. Some researchers speculate that releasing agents such as amphetamine pharmacologically replicate some of the neurobiochemical and neurodegenerative features of mania.

- Past amphetamine users are known to have a greater risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. It is worth noting that Parkinson’s disease is not evident until about 80% of dopaminergic neurons are already dead. If only e.g., 50% of dopaminergic neurons are dead this would not be noticed clinically. However, behavior, emotions, and baseline neurocognitive functions may be somewhat impaired, even though not to a “clinically relevant” extent.

Some researchers speculate that amphetamine is at the very minimum toxic to dopaminergic neurons. Dopamine-producing cells are among the most vulnerable populations of neurons in the human brain. They are naturally subject to toxic dopamine metabolites generated by the metabolism of dopamine through MAO-B. This results in a natural and gradual loss of dopaminergic neurons throughout life. The importance of dopamine is discussed in more detail here: The Brutal Neglect of Dopamine

At birth, a human brain contains about 500.000 dopamine-producing neurons, in some people more, in others less. It is thought that humans lose about 3.000-5.000 of these dopaminergic neurons per year. It is conceivable that this natural loss of dopaminergic cells is sped up by amphetamine use, either through MAO-B-generated toxic dopamine metabolites, excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, or a combination of these.

For some reason, combining caffeine with amphetamines increases the neurotoxicity of the latter.

Do we know for certain whether the therapeutic use of amphetamine is neurotoxic or not?

In short, no.

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

When searching for “amphetamine neurotoxicity” in Medline (PubMed) one can find a lot of papers on the subject with sometimes contradictory results. Judged by the currently available evidence, it seems fairly likely that high doses of amphetamine administered for a prolonged period of time have a host of adverse effects on brain health, including neurotoxicity.

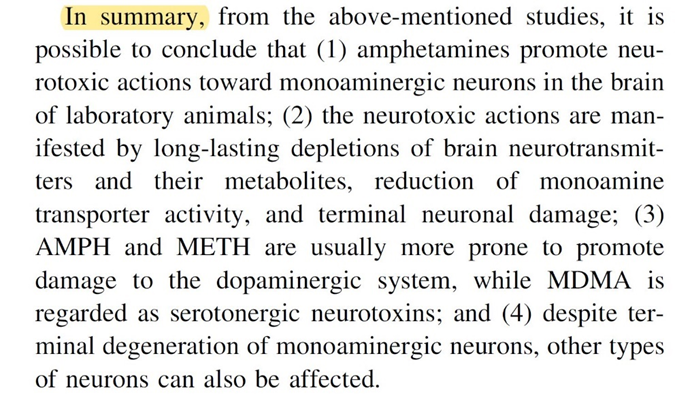

As mentioned in the cherry-picked snippet of a section of a study above, it has been known for a long time that high doses of amphetamines can cause neurodegeneration and impair cognitive function in laboratory animals as well as humans. However, most of the evidence comes from high-dose studies.

But the million-dollar question is whether therapeutic doses of amphetamines are sufficient for some of the neurotoxic damage to occur to an extent that it is relevant in real life. The answer to this question is currently unknown.

For a number of reasons, there will probably not be a study that can give us a clear-cut answer any time soon:

- unfeasibility of measuring “neuronal loss” or microscopic brain damage

- prolonged exposure and follow-up required (For example, it took over 20 years before some of the severe side effects of SSRIs such as valvular heart disease, increased risk of death from bleeding, and PSSD emerged – discussed here.)

- big pharma incentives (Currently, amphetamines make pharma companies billions of dollars per year.)

Some observational studies do indeed suggest that individuals who use amphetamines for extended periods of time are at an increased risk for developing cognitive impairment and dementia later in life, particularly Parkinson’s disease (which is characterized by the progressive death of catecholaminergic neurons). However, observational studies are incapable of proving causality.

Furthermore, it is important to understand that neurotoxicity is neither something people “feel” nor an all-or-nothing issue. Analogous to the fact that Parkinsonian symptoms only develop when over 80% of dopaminergic neurons have already died, most people can presumably sustain a fair amount of brain damage, before (clinically relevant) symptoms become evident.

I personally believe that the therapeutic use of amphetamines for prolonged periods of time is at least somewhat neurotoxic, albeit I don’t dare guess the extent. Given that it is known for certain that methamphetamine is neurotoxic, I would be surprised to learn that therapeutic use of amphetamine is not at all.

Unfortunately, the potential long-term consequences of amphetamine use, such as neurotoxicity, long-lasting changes in brain network and gene reregulation, are rarely discussed by the doctors who prescribe them.

It is quite concerning to see that a lot of physicians, especially in the US, prescribe amphetamines like candy. “Oh, you are a little tired and have a hard time keeping up with work and life? Do not worry about sleep, diet, exercise, hormones, metabolic health. Just have some Adderall.”

Adderall is in a sense similar to anabolic steroids. Online anecdotes tend to paint a “great cheat code for life” picture. However, that picture is very misleading and does not really capture the whole storyline. Lots of cheerleading first-time users who stop documenting their downfall seem to be a common theme.

It also makes one wonder whether so many people getting prescribed medical amphetamine brought about the meth epidemic in the same way that so many people being hooked on oxycodone brought about the opioid crisis.

Life is all about tradeoffs

Even if it were proven that the therapeutic use of amphetamines is neurotoxic, would that make using them a bad choice? Not necessarily.

When I was interning in psychiatry, I remember a patient who got prescribed methylphenidate (we Europeans rarely use amphetamines). Three weeks later he came back and mentioned that he had cut down the number of energy drinks from five to one per day, he stopped eating sugary snacks, and barely smoked any weed. Even though he was still in the honeymoon phase, if he can maintain some of his positive lifestyle changes, his stimulant prescription is presumably the lesser evil and much less neurotoxic than the e.g., weed.

During this period, he also started caring about university again. Hypothetically, if his stimulant medication helps him to complete university he would otherwise have dropped out of, one could argue that his life will be changed for the better and some neurotoxicity is a fine price to pay for that. In fact, what he will create and achieve on stimulants will stay with him.

Last but not least, I remember him saying that he started to enjoy life again. Given that it will always be now, his increased moment-to-moment well-being may well be worth some amount of brain damage.

Related articles on drugs of abuse

- Thoughts on THC

- Thoughts on Opioids

- Ketamine is Probably More Neurotoxic Than You Think

- Why Does Nobody Talk About Hallucinogen Persistent Perceptive Disorder?

- How Neurotoxic is MDMA?

- Is Adderall/Vyvanse Neurotoxic?

Sources & further information

- Scientific review: Toxicity of amphetamines: an update

- Scientific review: Amphetamine-related drugs neurotoxicity in humans and in experimental animals: Main mechanisms

- Scientific review: The ugly side of amphetamines: short- and long-term toxicity

Disclaimer

The content available on this website is based on the author’s individual research, opinions, and personal experiences. It is intended solely for informational and entertainment purposes and does not constitute medical advice. The author does not endorse the use of supplements, pharmaceutical drugs, or hormones without the direct oversight of a qualified physician. People should never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something they have read on the internet.