MDMA is a substituted methamphetamine that reliably produces an empathetic peak experience. As Dr. Claudio Naranjo puts it, this “penicillin for the soul” offers “a fleeting moment of sanity”.

However, given that so many people take MDMA, it is important to know about its safety – or a lack thereof.

Personal experience

I have taken MDMA a handful of times, each separated by about 1 year. Because I loved these sessions so much, I really looked forward to them.

The setting was always lame and the same: I spent an entire day talking to a good friend at a park. Every time an intense and bonding conversation ensued. Compared to how I felt on MDMA, my normal baseline state has the emotional intensity of a zombie.

The days after, I was always slightly hungover, but I have never experienced “Suicide Tuesday” – likely thanks to a stack of brain-protective supplements I have taken a couple of hours before. These included selegiline, vitamin C, vitamin E, alpha lipoid acid, N-acetylcysteine, coenzyme Q10, and SAM-e.

Even though each of these experiences was great, I somewhat regret them. I did these “sessions” long before I truly grasped the consequences.

My brain is my most valuable organ. It is the foundation through which I experience, think, feel, and act. While MDMA certainly has therapeutic potential (e.g., for PTSD), a sufficiently high dose of it is presumably quite neurotoxic, perhaps even exceeding the neurotoxicity of a single dose of methamphetamine (which though is more addictive).

I have on the order of only 200.000 serotonergic neurons and 500.000 dopaminergic neurons, both of which I prefer not to lose. MDMA is known to lead to lasting impairments in both transmitter systems, especially the serotonin system – more on that shortly.

How it works

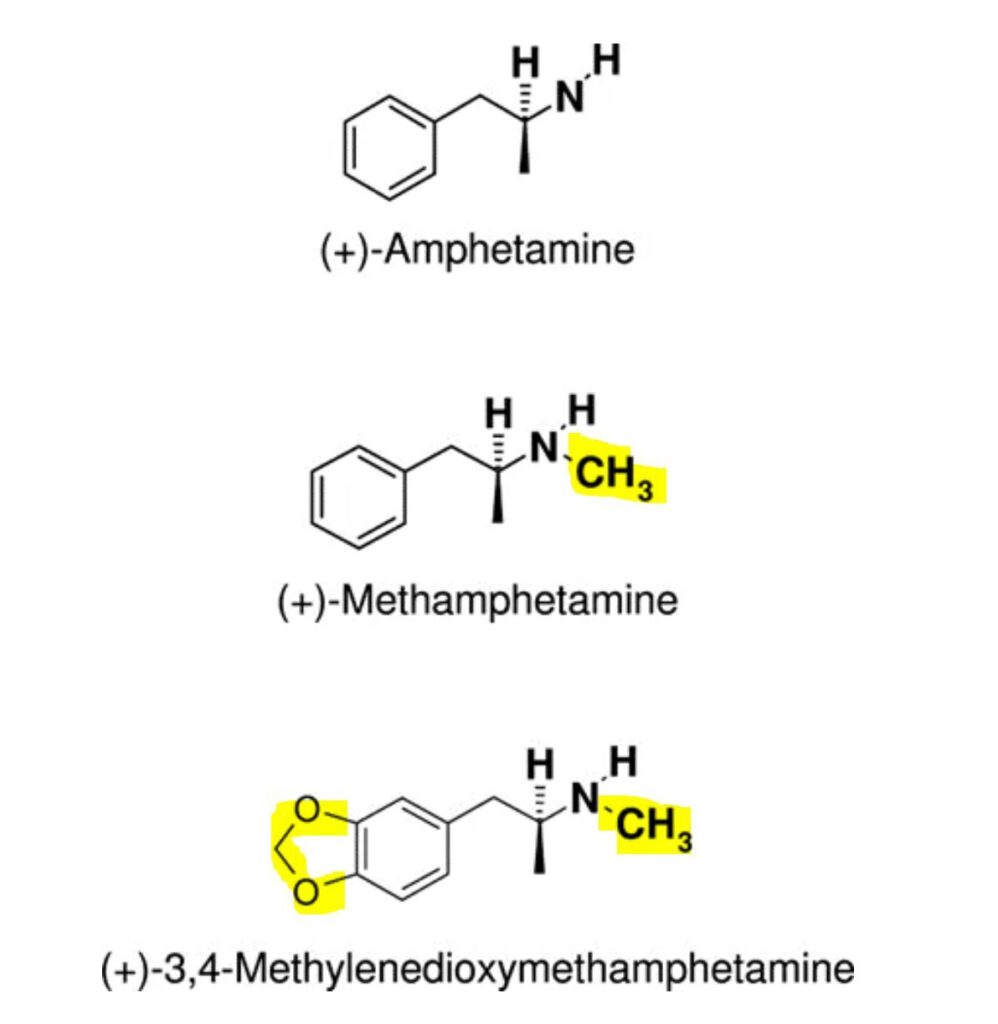

Andrew Huberman and Joe Rogan have a podcast in which they both ridicule researchers who mistakenly used methamphetamine instead of MDMA in their research on the neurotoxicity of MDMA. They were talking as both of these molecules would be utterly different and “how could they have been so stupid to make this mistake” – they did not seem to know that MDMA itself is a substituted methamphetamine – I think Huberman finally got the hang of it as a lot of people were complaining about his lack of understanding.

MDMA is a substituted methamphetamine – Methylene-Dioxy-MethAmphetamine (MDMA). Similar to the parent compounds amphetamine (Adderall), methamphetamine has an affinity for the dopamine transporter (DAT) and noradrenaline transporter (NET) but not so much for the serotonin transporter (SERT). The major difference between methamphetamine and methylenedioxy-methamphetamine is that MDMA has a much greater affinity to the serotonin transporter (SERT). However, other than their differences in affinities for different monoamines, their mechanism of action is nearly identical.

In simple terms, MDMA binds to neurons that have monoamine transporters on their cell membrane (dopamine-producing neurons have DAT; noradrenaline-producing neurons have NET; serotonin-producing neurons have SERT).

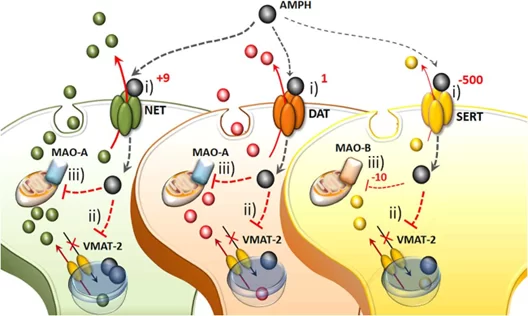

Some MDMA molecules block these transporters which leads to an accumulation of monoamines in the synaptic cleft. Other MDMA molecules enter the cell where they activate a special receptor called trace-amine-activated receptor 1 (TAAR1) which leads to an efflux of monoamines which then leads to an even greater accumulation of monoamines in the synaptic cleft. MDMA also blocks the monoamine transporter VMAT-2 and MAO-A, which though is presumably of lesser importance.

These monoamines then stimulate receptors both on the target neuron and the synapse itself. Because there is a great accumulation of monoamines within a short period of time, the effects of MDMA can be greatly “felt” by the user. In simple terms, the accumulation of dopamine leads to euphoria, the accumulation of noradrenaline to intense wakefulness, and the accumulation of serotonin to a feeling of warmth and contentment. These neurotransmitters and their transporters are discussed in more detail here: An Introduction to Neurotransmitters (and How to Modulate Them).

Therefore, MDMA is a triple-releasing agent, releasing dopamine, serotonin, and noradrenaline.

It is thought that the increase in serotonin release caused by MDMA is about five times greater than the dopamine release. The accumulation of dopamine contributes to the euphoric effects of MDMA while MDMA’s actions at the serotonin system are thought to underly its potent empathogenic effects (“full of love”). The concomitant increase in oxytocin likely also plays a role, though presumably minor.

As per philosopher David Pearce: “If one has tasted, say, the emotional release, self-insight and empathetic bliss of pharmaceutically pure MDMA, then it’s hard to accept the third-rate imitation of mental health bequeathed by natural selection.”

Unfortunately, this empathetic bliss comes at a price. The accumulation of monoamines is so great that the neurons become overstimulated and some of these neurons die because of too much stimulation (excitotoxicity). The flood of monoamines, the very thing that causes the blissful feeling, is what causes the neurotoxicity.

How neurotoxic is MDMA?.

A single potent dose of MDMA depletes brain serotonin levels by about 80%, which is often followed by so-called “Suicide Tuesday”, as monoamines were depleted and people’s thoughts and outlooks follow suit. Some people recover quickly, while others have a protracted depression-like state. Supplementing with 5HTP only partially helps!

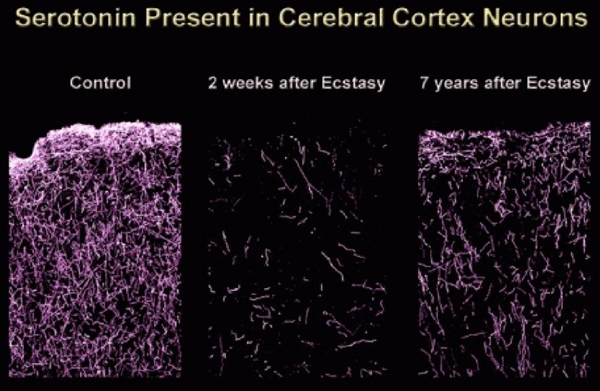

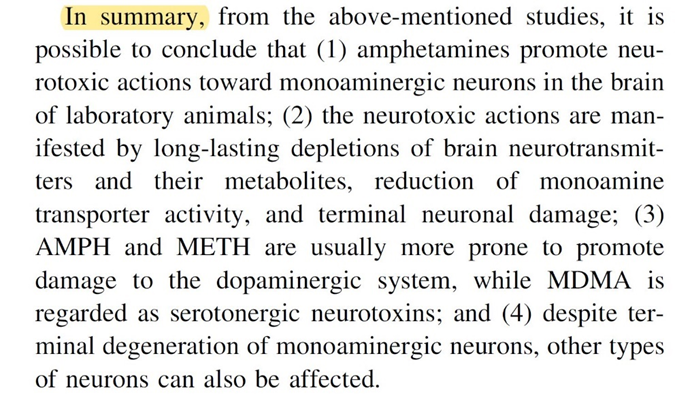

Animal studies using high doses of MDMA have shown some long-lasting loss of serotonergic tone in the brains of animals, which implies that some serotonin-producing neurons and/or their nerve endings must have died.

The fact that users never recapture the “magic” of their first trip suggests that MDMA may induce permanent changes. Some researchers believe this to be due to enzyme induction, but the more likely explanation is, in my opinion, neurotoxicity to serotonergic nerve endings and perhaps even serotonergic neuron cell bodies in the same way that methamphetamine has been proven to be toxic to dopaminergic nerve endings and cell bodies.

We know for certain that amphetamines (incl. methamphetamine) in high enough dosages are neurotoxic. I discuss the neurotoxicity of amphetamine including therapeutic use such as with Adderall/Vyvanse in more detail here.

There is also evidence from animal studies that MDMA may be toxic to the dopamine system in a similar way to methamphetamine – in addition to its toxicity to the serotonin system. I would be surprised if this were not the case.

The neurotoxicity of amphetamine, methamphetamine, and methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA) are all due to intense stimulation through a large flood of monoamines. This results in a variety of neurotoxic mechanisms, including oxidative stress, excessive calcium influx (excitotoxicity), toxic dopamine metabolites having undergone reuptake by serotonergic neurons (which can be prevented by pre-treatment with MAO-B inhibitors), and impaired cellular energetics. The elevated body temperature (hyperthermia) caused by MDMA plus dancing just makes things worse.

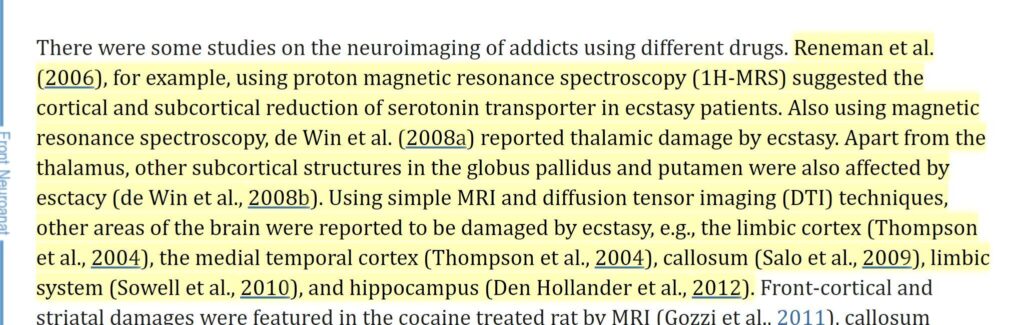

However, the biggest issue in proving MDMA neurotoxicity in humans is that microscopic brain damage cannot be measured with current technologies (other than slicing up a brain and examining it under electron microscopy). The fact that some studies find visible brain damage points to the damage being quite advanced in some users – similar to ketamine.

As always, some people like to overdo things.

While this is not an average user, and thus it can in no way be generalized, the Englishman paid a high price for his cumulative intake of 40.000 pills and now, 7 years after completely stopping the drug (reportedly), still suffers from extreme memory problems (he literally has the memory of a goldfish forgetting everything minutes after it happened), paranoia, hallucinations, and depression. He also suffers from painful muscle rigidity around his neck and jaw which often prevents him from opening his mouth. His condition is most likely permanent because dead neurons cannot undie.

For some reason, combining caffeine with MDMA increases its neurotoxicity, which holds true for amphetamines in general.

Neurotoxicity prevention stack

Because MDMA is neurotoxic due to multiple mechanisms, it is an illusion that a handful of supplements can prevent all of its neurotoxicity. However, supplements may reduce some of the neurotoxicity (my intuition would say by about 20-40%).

- vitamin C: water-soluble antioxidant (combats oxidative stress)

- vitamin E: lipid-soluble antioxidant

- alpha lipoid acid: molecule that leads to the upregulation of antioxidant systems

- N-acetylcysteine: major cellular antioxidant

- coenzyme Q10: lipid soluble antioxidant

I discuss these antioxidants in more detail here: Supplements I Take and Why

Summary

Unfortunately, research results are inconclusive and the extent of MDMA neurotoxicity is not known because it is nearly impossible to measure neuronal loss and damage to axon terminals at a microscopic level. However, extrapolating from animal experiments and what is known from the toxicity of the parent compound methamphetamine, methylenedioxy-methamphetamine is probably considerably more neurotoxic than most people appreciate. It specifically targets dopamine and serotonin-producing neurons, which are already very few in number and which people should try their hardest not to lose.

Most importantly, neurotoxicity is a one-way street as dead neurons will remain dead forever – along their connections. This is particularly worrisome if functionally very important neurons are affected, such as the few neurons available that produce dopamine and serotonin.

Just as always, the dose makes the poison. 1mg of MDMA is certainly not neurotoxic, 20mg of MDMA is probably not neurotoxic, 100mg is probably neurotoxic, and I would be very surprised if there were no neurotoxicity from a 200mg dose. My intuition tells me that the sweet spot may be around 30-50mg, particularly if protective supplements are taken and if body temperature is kept normal, but I have no evidence to back this up.

Bonus Section: Thoughts on Cocaine & Methamphetamine

In this article, I discuss common stimulants of abuse. Non-stimulant drugs of abuse are discussed elsewhere:

- Thoughts on THC

- Thoughts on Opioids

- Ketamine is Probably More Neurotoxic Than You Think

- Why Does Nobody Talk About Hallucinogen Persistent Perceptive Disorder?

- How Neurotoxic is MDMA?

- Is Adderall/Vyvanse Neurotoxic?

Methamphetamine (“Meth”)

The “therapeutic” use of amphetamine is discussed here. Lisdexamphetamine, a longer-acting version, is discussed here. In this section, I will briefly discuss some aspects of recreational amphetamine abuse, mostly in the form of methamphetamine.

Methamphetamine is a much longer-acting and more potent form of amphetamine. Once upon a time, it used to be prescribed for ADHD, lethargy, and obesity, but it did not take long before it was found to be addictive. Therefore, other than in China (where it is still sometimes prescribed for ADHD), most methamphetamine use is nowadays mostly illicit. Methamphetamine is widely abused particularly in the US and South-East Asia.

During WWII, methamphetamine was marketed as an OTC drug in Nazi Germany with the name Pervitin, dubbed Panzerschokolade (“tank chocolate”), which German soldiers used widely to boost energy and morale, especially during the Blitzkrieg period.

It is likely that Hitler and some others of the Nazi leadership had become meth addicts towards the end of the war. Some historians assume that some of their “grand” visions may have been meth-inspired. Hitler became addicted to methamphetamine presumably towards the end of the war. For a video about Hitler “tweaking”, see here.

During WWII, a few billion methamphetamine pills have been consumed by the Japanese, which amounts to hundreds of pills per person (including factory workers). Some historians believe that much of the country was on meth, and this may have contributed to their reported “toughness” and aggression. For example, the brutality during the Rape of Nanking (300.000 people executed; roughly 50.000 rapes) as well as the bravery required for Kamikaze may have well been “influenced”. In sum, some historians argue, that the Japanese would not have behaved like the Japanese if it were not for methamphetamine.

It is safe to say that without amphetamine and methamphetamine, the second world war may have played out differently.

Personal experience

Never tried it and I do not know of anyone who has (admitted to trying it).

How it works

The cellular mechanism of action between amphetamine and methamphetamine is quite similar. Both inhibit monoaminergic transporters (DAT, NET, SERT) and both are potent agonists at the trace-amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR-1), which causes the release of monoamines.

However, The addition of a methyl group to amphetamine leads to three key changes that distinguish methamphetamine from amphetamine:

- It becomes more lipophilic and therefore able to cross the blood-brain barrier more readily.

- It becomes more resistant to degradation by MAO-enzymes, and less readily excreted via the kidneys, which doubles the half-life from about 10 hours to about 20 hours.

- Its affinity for the serotonin transporter (SERT) increases.

Consequences

Methamphetamine use does a lot of damage. Users are frequently aware of this but “I don’t care if I can feel always like I do now.”

At high doses, there is little speculation that amphetamine (“speed”) or methamphetamine are far from safe. Among other things, it can cause dangerous elevations of blood pressure (with all of the structural damage that entails), the cumulative effects of undereating and undersleeping, confusion, rapid mood swings, and pathological changes to the myocardium (which can cause arrhythmias and hypertrophy), and a lot of adverse changes to the brain

Chronic meth abuse severely damages the heart (cardiomyopathy) and ejection fractions of below 20% are not unheard of. Many times, the cardiac complication will result in early death. Furthermore, meth frequently causes psychotic episodes, and psychotic-like states frequently persist for many years even after the drug has been stopped.

“Meth mouth” is thought to be due to xerostomia (the inhibition of salivary glands) and bruxism (teeth grinding). The former is thought to be due to a strong rise in noradrenaline, while the latter is related to abnormalities in the dopamine system. Furthermore, methamphetamine addiction may cause users to lose interest in self-preservation, and the lack of hygiene and basic self-care probably does not help either.

The cause of “meth skin” is unknown but some researchers hypothesize that the cutaneous vasoconstriction may lead to tingling and itchiness, which then may cause users to excessively scratch.

Methamphetamine is also a potent aphrodisiac. It skyrockets libido, increases energy levels and mood, and inhibits ejaculation and orgasm. The combination of “very horny” but “I cannot orgasm” is what leads to its abuse for “stimfapping” (people masturbating for many hours on stimulants) or by the gay party & play community to allow “users” to engage in promiscuous chemsex orgies for many hours, sometimes days. A psychiatrist friend of mine once had a patient who had contracted every STD under the sun (including HIV & HCV) during such an orgy due to (reportedly) having had sex with about sixty guys in a single night.

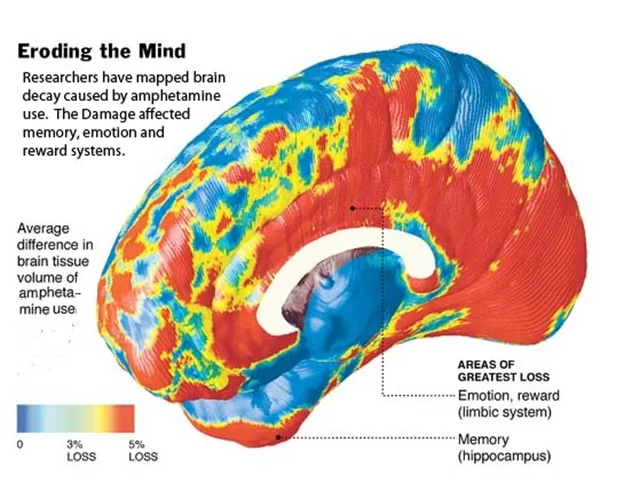

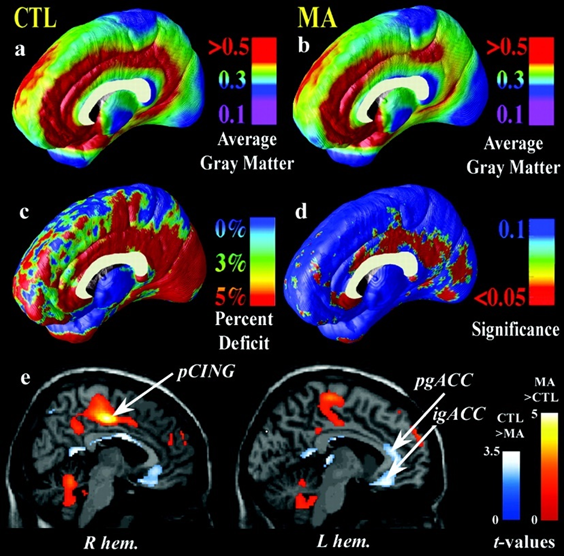

Because of its greater potency, methamphetamine is more neurotoxic than amphetamine, though both are neurotoxic at high enough doses. The neurotoxicity probably extends way beyond monoaminergic systems, and there is evidence that prolonged use of methamphetamine can cause atrophy and brain damage in many brain regions. Even low doses (in the therapeutic range) may be neurotoxic – though this is still a matter of debate. Discussed in more detail here: Is Vyvanse/Adderall Neurotoxic?

The picture below compares grey matter volume between controls and methamphetamine users.

Due to the destruction of the dopamine system due to overstimulation plus toxic dopamine metabolites, methamphetamine abuse can result in early-onset Parkinson’s disease.

Addiction potential

Below is a copy & paste from a user describing what it was like to come down after using methamphetamine for the first time:

“I’m pretty happy most of the time, and I don’t have any problems with depression. So, feeling ‘depressed’ after using the drug really bothered me. I really, really wanted to stop feeling that way, which didn’t make sense, because rationally, nothing was really very wrong.

The depression wasn’t very strong, and I was able to tell myself it was just a hangover, and I could ride it out, but I could see that if it was much stronger, I might do just about anything to make it stop. Again, I don’t know how to explain it any better than this, and I’m not sure I could make it make sense to someone who hadn’t experienced it, but it was like the ‘make this state of being stop’ was its own powerful emotion, whereas usually, it is the result of some other thing in my environment or my thoughts that is upsetting me.

Because it was its own emotion, there was basically nothing I could do to ‘fix’ it. It’s not like I was hungry and needed to eat, or sleepy, and needed to go to bed. It was just a sense that something unspecified wasn’t right, and so there was nothing to be done to make it better. Except, I’m sure that doing another bump would have made it better. I always thought of addiction as a craving for the drug itself, but here, the addiction could come as a medication for the drug’s after-effects.”

Stimulant psychosis

Among the most dangerous side effects of amphetamine abuse is stimulant psychosis (hallucinations, paranoid delusions, super weird thinking patterns, bizarre and repetitive behaviors). The symptoms of acute amphetamine psychosis are quite similar to those of the acute phase of paranoid schizophrenia.

A friend of mine, who is a psychosis researcher, uses amphetamine administration as his method of choice to induce psychotic-like states in laboratory animals because, to put it in his words, “amphetamine-psychosis is the only real psychosis”. (He is referring to the fact that drug-induced psychoses from ketamine or psychedelics are neurobiologically different, whereas psychosis from amphetamine mimics the neurobiological aspects of psychosis from schizophrenia much more closely).

In fact, if amphetamines are given at a high enough dosage for a long enough time, almost everyone will experience psychosis, even if the individual does not have a genetic predisposition. Furthermore, dopaminergic neurons and related brain networks may change in such a way that psychotic-like states may become recurring events.

Amphetamine psychosis seems to be particularly common in South East Asia.

Interestingly, if dopamine release is measured experimentally, individuals with strong risk factors for schizophrenia show a much higher dopamine release for the same amount of amphetamine compared to healthy controls pointing to a “sensitized” dopamine system.

Cocaine

Supposedly, cocaine is the ultimate fun drug. After cannabis, cocaine is the second most widely abused illicit drug worldwide. While many people abuse it recreationally, there seems to be a large number of people who “use” cocaine as a nootropic stimulant. Whether (ab)used as a stimulant, nootropic, aphrodisiac, or euphoriant, cocaine is a powerful drug, but this power comes at a price – not just financially.

Personal experience

I never tried it though a couple of friends have, and they reportedly felt “on top of the world”: incredible motivation, a feeling of being invincible, insatiable drive, great mood, strong focus, and, most importantly, a spectacular sense of importance and purpose.

Interestingly, one friend fell asleep shortly after. We are all different.

How it works

Cocaine is a serotonin-dopamine-noradrenaline-reuptake inhibitor (SDNRI). It inhibits monoamine transporters in this order: DAT > NET>>SERT. This is actually quite similar to methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta) but the onset of action of cocaine is much more rapid.

Any dopaminergic drug that peaks swiftly in the bloodstream produces a high. For example, if modafinil or bupropion are snorted or injected, they produce an addictive “high” even though both of these drugs, if given orally, have very low addiction potential. Cocaine’s strong euphoriant properties are a function of its very short time to peak, seconds with crack cocaine, and minutes with intranasal administration.

The cocaine high is reportedly characterized by a rapid and strong euphoric rush followed by a nasty comedown or crash, which is caused by the counterregulation to the massive but short-lived increase in neurotransmitters.

Cocaine’s ability to elevate striatal dopamine levels is almost unparalleled. Therefore, it is thought to be one of the most addictive drugs known to mankind, perhaps about equal to heroin and slightly less than methamphetamine. Even a single exposure can change gene transcription patterns in the nucleus accumbens in a way that can be measured (and possibly felt) for weeks after.

Risks

Cocaine addiction is not just financially ruinous. Cocaine use is associated with a number of risks. Due to its powerful effect on catecholamines, cocaine use can (and likely does) damage the heart. The cardiotoxic potential of cocaine has been known for a long time. Tens of thousands of cocaine (ab)users are admitted to the ER every year because of this.

In rare cases, the intense spike in blood pressure following consumption can result in cerebral hemorrhage, especially if one has a preexisting aneurysm. Furthermore, cocaine can cause stimulant psychosis (discussed shortly), with more than half of users describing some form of psychotic symptoms at some point. And all of this for a peak experience of not even 30 minutes.

Cocaine is presumably less neurotoxic than amphetamines (e.g., methamphetamine, MDMA) but it frequently causes psychosis and hallucinations. More than half of regular cocaine users will have psychotic symptoms at some point.

Potential treatment for cocaine addiction

Multiple drugs are useful for combatting cocaine addiction.

- One of these anti-cocaine drugs is methylphenidate, which is quite similar to cocaine in terms of its mechanism of action. The major difference is the route of administration and the time it takes to peak.

- Modafinil binds to the same binding site on the DAT as cocaine, albeit with a much weaker affinity. Furthermore, in comparison to methylphenidate, modafinil has no affinity for NET and SERT. Modafinil reportedly reduces some of the craving associated with coke addiction.

- Bupropion, which is an amphetamine derivative, is a useful “anti-addiction” agent in general as it increases baseline energy levels and mood.

- Anecdotally, GLP-1 agonists such as semaglutide or tirzepatide do not just target food addiction but their anti-addiction effects seem to be broader

- Some other potentially useful drugs are described in the section “Noteworthy Molecules in the Pharmaceutical Pipeline”.

- In the coming years, there may be a vaccine against cocaine (a cocaine metabolite bound to the inactivated cholera toxin) that may be able to neutralize cocaine molecules as soon as they enter the bloodstream. This would be a one-time-and-done treatment. From the point of vaccination on, the effects of cocaine may be irreversibly off limits.

I discuss addiction in more detail here: Kicking Addictions – Potentially Helpful Agents

Sources & further information

- Case report: The strange case of the man who took 40,000 ecstasy pills in nine years

- Scientific review: Short- and long-term toxicity of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ‘Ecstasy’)

- Scientific review: Neurotoxicity of MDMA: Main effects and mechanisms

- Documentary: The Meth Epidemic

- Scientific article: Methamphetamine: an update on epidemiology, pharmacology, clinical phenomenology, and treatment literature

- Anecdotes: Erowid Vault – Methamphetamine

- Website: PsychonautWiki – Cocaine

- Scientific review: DARK Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: Cocaine

- Experience reports: Erowid Vault – Cocaine

- Scientific review: Potential Adverse Effects of Amphetamine Treatment on Brain and Behavior: A Review

- Scientific review: Amphetamine-induced psychosis – a separate diagnostic entity or primary psychosis triggered in the vulnerable?

- Scientific review: Stimulant psychosis: systematic review

Disclaimer

The content available on this website is based on the author’s individual research, opinions, and personal experiences. It is intended solely for informational and entertainment purposes and does not constitute medical advice. The author does not endorse the use of supplements, pharmaceutical drugs, or hormones without the direct oversight of a qualified physician. People should never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something they have read on the internet.