Long-term brain changes

As people meditate, they “train” certain neural networks. As these networks are activated, they will strengthen. Networks that are activated less, will weaken (“Use it, or lose it.”). There are tons of fMRI studies confirming long-term brain changes in people who start to meditate. This is somewhat analogous to training a specific movement. If practiced enough times and with enough force, it will induce musculoskeletal adaptation.

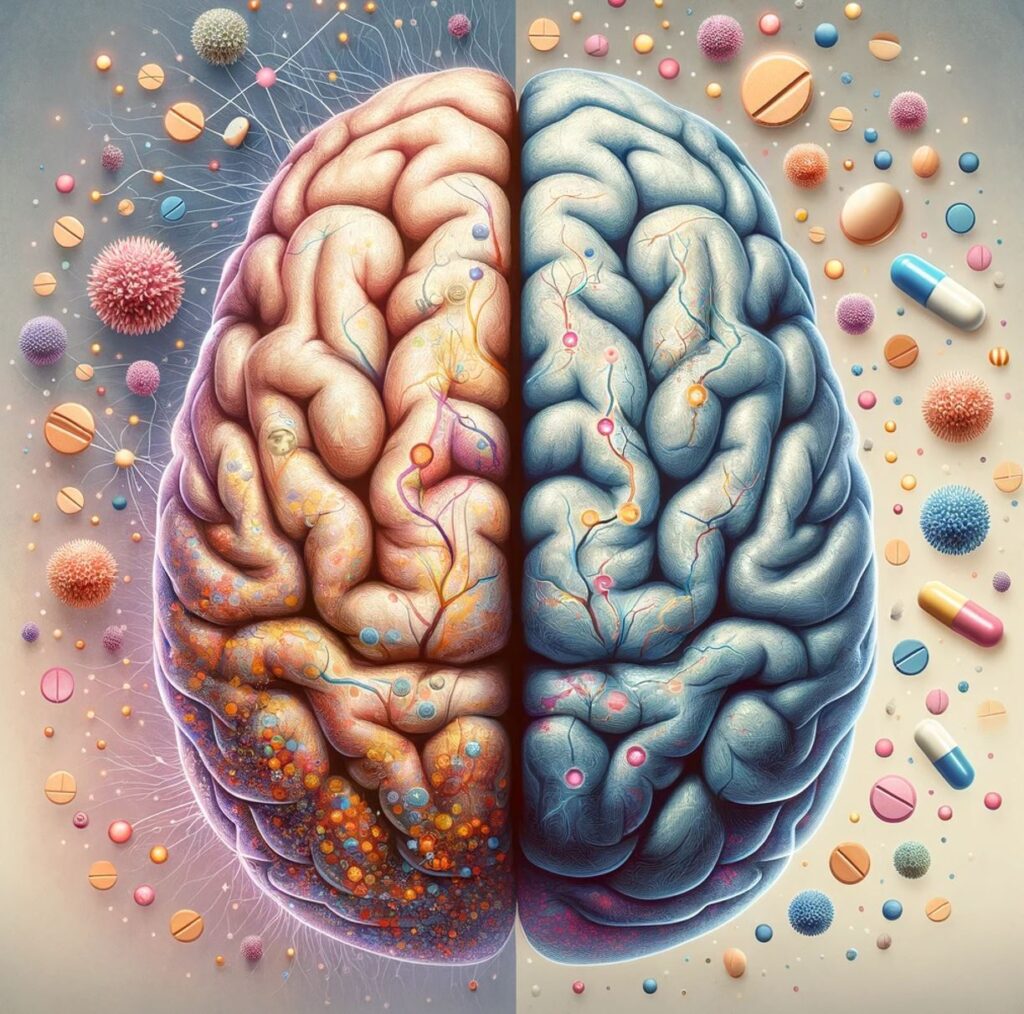

In the same way that anabolic steroids will alter muscle biochemistry for many years to come, similar things hold true for antidepressants and other psychotropic molecules leading to long-term brain changes.

As people start to take a psychotropic molecule (e.g., psychedelics, modafinil, SSRIs), brain chemistry changes. However, as with meditation, the brain structurally adapts depending on how it is used. And if there is a neuropharmaceutical present, the brain will be used somewhat differently. Therefore, regardless of long-term safety, every neuropharmaceutical will not just change brain function acutely (i.e., while the molecule is in the system) but will also have long-term effects on brain structure – something that is rarely discussed.

Therefore, as the brain, and the neurons that comprise it, begin to adapt and rewire, personality changes. My personality is nothing other than my typical pattern of thinking, feeling, and acting, which depends in part on brain wiring and neurotransmitters, both of which are altered by neuropharmaceuticals.

These changes may persist for a long time to come, and potentially forever – often without the person being aware. While this is not necessarily a bad thing, before people start experimenting blindly, they should be aware that the brain, and personality, may never quite go back to where exactly it was before, which though is often the point.

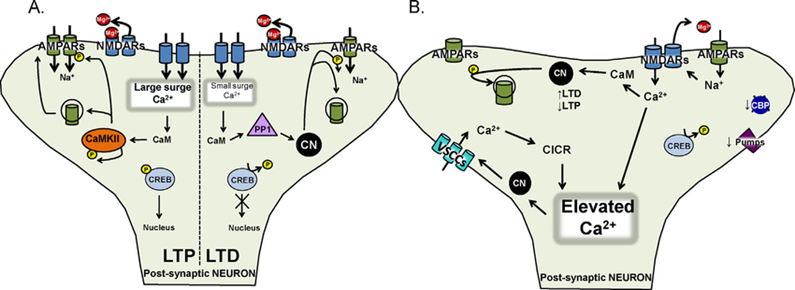

On neuropharmaceutical drugs, certain brain networks and pathways are more active and as these pathways are used more often there is a progressive strengthening of the synapses involved, also known as long-term potentiation (LTP).

However, not just whole brain networks, but also individual neurons undergo long-term changes. These include changes in transcription factors and gene methylation, and consequently gene expression patterns. Unfortunately, this is quite an under-researched field.

In sum, depending on the molecule, dosage, duration, and age (more powerful if a brain is not fully developed), some of the changes will persist for months, years, and potentially forever.

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

Examples:

- SSRIs make users more rational and less emotional not just by increasing serotonin levels acutely, but also by changing the structure of the brain. Among many other structural adaptations, being on SSRIs results in a reduction in the size and cytoarchitecture changes of the amygdalae. Therefore, a slight reduction in anxiety and emotional blunting may persist for a long time after the drug is out of the system. SSRIs are discussed in more detail here.

- Because of catecholaminergic dysregulation, the brains of individuals with ADHD differ in certain aspects from the brains of “normal” people. After years of ADHD treatment, these changes tend to “reverse”. Neuroanatomically, this is reflected by a grey matter increase in certain brain structures associated with attention (e.g., caudate nucleus), though perhaps at the expense of creativity. The upsides and downsides of ADHD treatment are discussed in more detail here.

Permanent damage is possible

Next to low-level alterations in brain structure, “permanent” damage is certainly not unheard of.

For example, PSSD after a course of SSRIs, tardive dyskinesia after taking antipsychotics, prolonged anhedonia after taking amphetamines, HPPD after taking psychedelics, aberrant synaptic pruning after smoking weed, loss of serotonergic neurons after popping MDMA, or excitotoxic loss of neurons after doing ketamine.

While some recovery may happen, in many of these cases recovery may take a long time (but may be incomplete).

Is it safe to take stimulants and antidepressants forever?

Most drugs licensed in a Western medical system are backed by long-term safety studies. Unfortunately, “long-term” usually means two years or less. With a couple of exceptions (e.g., metabolic drugs, lipid-lowering agents), there are few proper truly long-term safety studies for most molecules discussed on this website.

However, this does not mean that the drugs are not suitable for life-long consumption, just that we do not know for sure.

In general, if dosages are in the therapeutic range, most stimulants (perhaps except for amphetamine) and antidepressants (perhaps except for ketamine) are likely fairly safe for decade-long consumption. However, most of the data available comes from mentally ill people, so it is hard to say for sure.

One could argue that in the case of severe, recurrent major depression, it might even be physically healthier for the brain to be on antidepressants, given that depression itself is associated with atrophy in a variety of brain areas.

Furthermore, the indirect effects of neuropharmaceuticals need to be considered as well. If I am depressed, have low energy & motivation, I am more likely to eat crappy, sleep shitty, forgo exercise, withdraw socially, and stay in the house. Conversely, diet, sleep, exercise, socializing, and environmental enrichment are all crucial to long-term brain health, and undoubtedly, antidepressants may help with these in the case of depression, as discussed here: What Kind of Antidepressant Should I Take?

However, there are known instances in which neuropharmaceuticals have adverse effects on brain health. I will now list a couple of these.

Psychiatric polypharmacy

It is more common than not for a psychiatric patient to be prescribed multiple neuropharmaceuticals at the same time. Instead of simplifying (most psychiatrists hate simplicity), whenever a new symptom (or side effect) arises, psychiatrists tend to add a new drug (instead of taking one away).

This is how patients end up with quite nasty cocktails quite fast. While polypharmacy is often needed, in many cases it may not be necessary but rather reflects incompetence.

The wondrous human brain is indeed quite adaptable and resilient. However, during my internships in several psychiatric wards, I have seen medication regimens that left me questioning whether the human brain remains relatively intact after a decade-long onslaught of soul-sucking combinations of psychotropic molecules.

Examples:

- Patient #1: 450mg moclobemide, 300mg bupropion, 450mg pregabalin, 400mg quetiapine. I did bring up that moclobemide should (must?) not be combined with bupropion, but the head of the psychiatry ward dismissed it despite the patient having had a blood pressure of 180/110 mmHg. According to him, they do this quite often…

- Patient #2: 90mg duloxetine, 300mg bupropion, 45mg mirtazapine, 5mg aripiprazole, 400mg quetiapine

- Patient #3: 450mg bupropion, 300mg modafinil, 5mg aripiprazole, 2mg alprazolam

- Patient #4: Sertraline, bupropion, brexiprazole, trazodone, hydroxyzine, and lithium. This patient commented that he believed that he was on too many drugs. Instead of taking meds away, they added Adderall to his regimen. (Unlike the other patients, I have not personally met this particular patient, but I came across his story on an internet forum – so I do not know whether this is actually true. But my personal experience with psychiatrists leads me to believe that it is.)

I share my thoughts, criticism, and experience with modern psychiatry in more detail here: Thoughts on Modern Psychiatry.

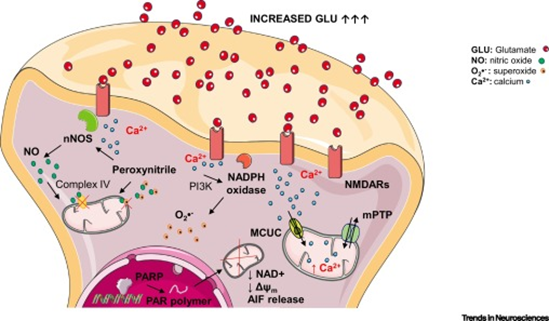

Excitotoxicity

Intense stimulation for prolonged periods of time is toxic to neurons, in part because excessive calcium influx triggers apoptotic cell death, also known as excitotoxicity. This is especially true for releasing agents such as MDMA, which is neurotoxic to serotonergic neurons, and amphetamine, which is possibly neurotoxic to noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurons – perhaps even at therapeutic doses (as discussed here).

The sneaky aspect is that neurotoxicity is not something one “feels” but rather something that occurs very gradually.

Synaptic integrity

Endocannabinoids play a crucial role as retrograde transmitters in maintaining synaptic integrity. There is a wealth of data showing that chronic THC consumption is “bad” (toxic) for the brain. I discuss this in more detail in the article on THC.

Antipsychotic-mediated motor problems

D2-blocking drugs may be toxic to dopaminergic neurons. This is well known for older antipsychotics, which are typically associated with tardive dyskinesias (progressive and irreversible problems with motor control presumably rooted in the structural degeneration of certain subsets of neurons). However, even low doses of the newer atypical antipsychotics are known to cause them. Antipsychotics are discussed in more detail here.

PSSD

In an analogous way that antipsychotics can lead to structural degeneration of certain dopaminergic pathways, it is conceivable that SSRIs cause post-SSRI-sexual dysfunction (PSSD) in an analogous manner. PSSD is discussed here.

Sources & further information

- Scientific review: Mindfulness Meditation Is Related to Long-Lasting Changes in Hippocampal Functional Topology during Resting State: A Magnetoencephalography Study

- Scientific review: Effect of Psychostimulants on Brain Structure and Function in ADHD: A Qualitative Literature Review of MRI-Based Neuroimaging Studies

- Scientific review: Brain Structural Effects of Antidepressant Treatment in Major Depression

- Anecdotes: Reddit – r/depressionregimens

- Scientific review: Cannabis effects on brain structure, function, and cognition

- Scientific article: Tardive Dyskinesia

Disclaimer

The content available on this website is based on the author’s individual research, opinions, and personal experiences. It is intended solely for informational and entertainment purposes and does not constitute medical advice. The author does not endorse the use of supplements, pharmaceutical drugs, or hormones without the direct oversight of a qualified physician. People should never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something they have read on the internet.