Stimulants, as their name suggests, are molecules that stimulate the nervous system. Most of these work by directly or indirectly increasing a variety of other neurotransmitters, first and foremost enhancing catecholaminergic signaling (dopamine or noradrenaline).

Why do people use stimulants?

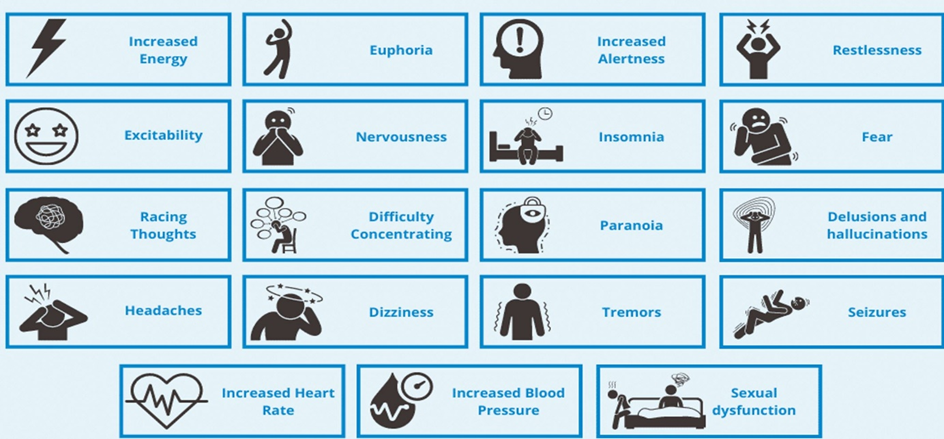

Desired effects are increased alertness, wakefulness, endurance, productivity, motivation, sociability, agency, and a diminished desire for food and sleep.

Energy levels

Most stimulants increase one or more of a variety of neurotransmitters, such as noradrenaline, dopamine, and histamine, and therefore increase energy levels, reduce perceived fatigue, and banish sleepiness. I find that life is decently better when my energy levels are good. This is one of the primary reasons I used to be addicted to caffeine in my early 20s – which in the end though reduced my energy levels overall.

Focus

When taken in low or therapeutic doses, stimulants enhance the ability to focus. However, in higher doses stimulants may do the opposite because too many things may become too salient at once, or because they induce anxiety or euphoria – both of which are not conducive to one’s ability to concentrate. From all the stimulants I have tried to boost focus, methylphenidate, which is frequently used to slow down hyperactive children, was probably the strongest – so strong, that I did not like being on it.

Cognitive performance

In certain situations, such as sleep deprivation or fatigue, stimulants increase executive functions and cognitive performance. Conversely, in healthy users devoid of adverse influences, stimulants are known to improve certain aspects of cognition, such as focus and memory retention, but seem to worsen others, such as creativity. A prime example of a more “cognitive” stimulant is modafinil, which is the only pure dopamine reuptake inhibitor currently in clinical use. I frequently use nicotine to boost my cognitive performance.

However, stimulants are also known to cause users to overrate their performance, as our subjective sense of how well we are doing is not a good predictor of how well we are actually doing.

Mood

Stimulants elevate vigor, mood, and self-confidence. Therefore, they are often prescribed off-label for depression. This is discussed in more detail here: The Brutal Neglect of Dopamine.

Invariably, whenever I use stimulants, my mood goes up – particularly if I have not used a specific stimulant in a long time. This may be due to mood and energy levels having a partially shared underlying neurobiology.

Sleep

Stimulants increase sleep latency, impair the orderly progression through sleep stages, and impair deep sleep. Furthermore, stimulants increase sleep needs. The increase in sleep needs coupled with the decrease in sleep quality is one of their main adverse effects. For example, when a friend of mine was on lisdexamphetamine, he was only sleeping 5-6 hours per night.

Libido

Stimulants increase sex drive, which is in part under dopaminergic control. For example, the antidepressant bupropion (an amphetamine derivative) is frequently prescribed to boost the decrease in sex drive caused by SSRIs. A stimulant that is particularly strong at boosting libido is yohimbine.

However, some stimulants can also cause erectile dysfunction, which has little to do with sex drive but more to do with reduced neural and vascular signals to the penis. For example, on cocaine, some people are incredibly horny but unable to get an erection.

Appetite

Stimulants decrease appetite, which is also in part under dopaminergic and noradrenergic control. Stimulants are therefore often used (or abused) as appetite suppressants. For example, ephedrine, a natural alkaloid similar to amphetamine, was abused widely in the 90s and early 2000s as an appetite suppressant and weight loss agent. As was and is sibutramine.

Sociability

Stimulants can make withdrawn or anxious people social butterflies, partly because of the greater energy levels and partly because of the slight euphoria stimulants tend to cause, both of which lead to a greater desire to interact with others. However, in some people, stimulants can amplify anxiety and reduce social desire and ability.

I personally rarely experience anxiety and stimulants tend to increase my desire to socialize. Conversely, when I am in a bad mood and/or have low energy, my desire to socialize is low.

Sympathetic nervous system (SNS)

Most drugs classified as stimulants are direct or indirect sympathomimetics. That is, they stimulate the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system. This leads to effects such as mydriasis, increased heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and body temperature. A stimulant I sometimes use to disinhibit my sympathetic drive is yohimbine.

Weight loss

By increasing SNS activity, stimulants increase basal metabolic rate (BMR). Depending on the molecules and dosage, BMR may rise anywhere from 20-50kcal per hour. Furthermore, by elevating peripheral noradrenaline levels and inducing adrenal adrenaline release, most stimulants increase lipolysis (the breakdown of triglycerides).

The combination of an increased metabolic rate and increased lipolysis makes them powerful weight-loss drugs (even if they did not suppress appetite) because weight loss is much more than just “calories in vs. calories out” – as discussed here.

Stimulants that are frequently used and abused for weight loss purposes are caffeine and ephedrine (the EC stack), yohimbine, and clenbuterol (an orally available b2-agonist).

Why are stimulants pleasurable?

Most stimulants induce a sharp rise in dopamine signaling. Whenever dopamine rises swiftly and strongly, endogenous opioidergic pathways are recruited in the nucleus accumbens shell, an important structure in the reward system and the brain’s major “hedonic hotspot” (discussed in more detail here) – the faster and stronger the rise, the more euphoriant the experience.

For example, modafinil and cocaine act on the same molecular binding site on the dopamine transporter (DAT), but one is much more pleasurable than the other, in large part due to the swiftness of onset.

This is the reason cocaine, and especially crack cocaine, is so pleasurable despite its action being completely outside the opioidergic system. Namely, cocaine administration leads to a rapid and massive accumulation of dopamine, which then recruits opioidergic pathways. Furthermore, human emotions are synthesized by many different components, and it seems that intense “wanting” itself is perceived as being pleasurable.

Principles for Responsible Stimulant Use

In my life, stimulant consumption may have done more harm than good, in part because the artificial elevation of neurotransmitters caused me to overlook baseline vitality. Nonetheless, I used a couple of rules and principles to make stimulant use a little more sustainable, with fewer adverse effects on my mind and body. To understand the principle behind these principles (the “meta-principle” so to speak), I first need to discuss the concept of “counterregulation”.

Counterregulation explained

Most people know that with repeated stimulant use the body develops a tolerance. This is partly incorrect. The concept of tolerance would imply that the stimulant was simply less effective next time, which is only part of the story.

There is not just tolerance, but rather a process of counter-regulation. Understanding the principle of counterregulation is, in my opinion, crucial for using stimulants responsibly.

Every physiological system, including every cellular system, is on a continuous quest for equilibrium. Whenever this equilibrium is perturbed, a host of counterregulatory mechanisms are set in motion to nudge the system back toward its original state.

Counterregulation occurs at every level of physiology: at the receptor level, at the cellular level, and at the system level.

Example: Somebody has a blood pressure of 160/100mmHg. An antihypertensive, such as a calcium-channel blocker, is given and within a day, blood pressure decreases to 130/80mmHg. However, a host of counterregulatory mechanisms are set in motion, and over the course of a couple of weeks, blood pressure gradually increases again to 140/90mmHg and stabilizes there.

If the blood pressure med is then suddenly withdrawn, blood pressure shoots up to 180/120mmHg, because the counter-regulated system overshoots the original state. Slowly over time, blood pressure decreases back to the original state.

In the case of stimulants, it goes like this:

- First, stimulant use leads to a depletion of neurotransmitters. At the same time, there is an adaptation at the receptor level, such as degradation or desensitization of stimulated receptors. These effects reverse quite rapidly (hours to days).

- If stimulants are taken repeatedly there is also an adaptation at the cellular level, such as the phosphorylation of proteins involved in cellular signaling. Therefore, once the effect of the ingested stimulant has worn off, neurotransmitter levels, receptor levels, and cellular signaling are all below baseline, leaving the user depressed, lethargic, confused, and miserable. This state, which is partly characterized by a reduction of dopaminergic and noradrenergic tone and signaling, is referred to as the “crash”.

- For long-term use of stimulants, there is also an adaptation at the transcriptional level (gene expression) and system level (changes in brain networks). These two adaptations are much more stubborn. Recovery to baseline can last weeks to months, and sometimes years.

Analogous adaptations are true for most other drugs as well. Many hormones are an exception because they act directly on gene expression (and not on G-protein-coupled receptors), which has little to no feedback loops. Hormones are discussed here.

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

Withdrawal

Withdrawal happens due to the process of counterregulation discussed above.

Depending on the dosage and length of use, withdrawal intensity can range from imperceptible to severely debilitating. For some individuals, withdrawal symptoms are short-lived, for others, a protracted withdrawal syndrome may occur, and symptoms are sometimes persisting for months or even years.

This syndrome is at least in part due to persisting physiological adaptations in the central nervous system. This includes disturbances in neurotransmitters, trophic adaptations in brain networks, as well as stubborn changes in gene expression and gene methylation patterns.

The following molecules are known to cause hard to hellish withdrawal syndromes:

- Alcohol & phenibut

Principles I followed to reduce counterregulation

Whenever I used stimulants without breaks, I encountered massive counterregulation, which is much more than just tolerance. The consequence was a progressive dose escalation to maintain effects. If I eventually came off, there was a nasty withdrawal.

For example, a couple of years back I worked in a sales job. During the workweek, I used modafinil and ephedrine daily. During the weekend, I took breaks. However, on weekends I felt sluggish as hell and all I wanted to do was watch YouTube videos because I did not have the energy to do anything else.

The stimulant withdrawal was characterized by the reverse of the stimulated state I was seeking in the first place (e.g., dysphoria vs euphoria, apathy vs motivation, lethargy vs alertness).

Over time, I learned how to use stimulants more responsibly, in the sense that I tried to minimize counter-regulation, and there were several principles that I used to abide by.

Prioritizing baseline vitality

If my baseline vitality was good, I was less tempted to use stimulants in the first place as I simply did not need them. Furthermore, on stimulants, I often forgot to eat, drink, and take care of my electrolytes. Dose escalation (and a nasty crash) was pre-programmed as my body can just give out what I put in (physics) – at least in the long run.

For me, the most important aspects of baseline vitality included putting a premium on sleep, making sure my caloric intake was sufficient, engaging in exercise, and optimizing hormones. I discuss these things in much more detail here.

Cycling stimulants

I always tried my best to not get dependent on a specific stimulant. To help with this, I often rotated, cycled, and alternated stimulants with a somewhat different mechanism of action. For example, on day 1 I took caffeine, on day 2 I took modafinil, and on day 3 I took ephedrine. Amphetamines are poorly suited to cycling because they are particularly harsh and even a single amphetamine day can cause a withdrawal lasting for more than a day.

Avoiding “peaks”

As a rule of thumb, euphoria was a pretty reliable guide when I had taken too much and/or the drug concentration had risen too fast. As discussed, stimulant euphoria happens when dopamine levels rise swiftly and strongly, which recruits the activation of opioidergic pathways in the nucleus accumbens shell.

While being “nice”, I knew that I would pay the price in the form of strong counterregulation. To reduce euphoria, I used the lowest doses possible and avoided drugs with a fast onset of action (e.g., sipping my coffee over the course of a couple of hours, modafinil, repeated microdoses of ephedrine instead of a single larger dose).

L-tyrosine instead of redosing

I often used L-tyrosine instead of redosing. L-tyrosine supplies the necessary building blocks for synthesizing catecholamines (dopamine & noradrenaline). Therefore, supplementing with it will replete neurotransmitters, which will allow me to use lower doses of stimulants, extend stimulant duration, and reduce the crash associated with stimulant comedown.

Detailed discussions of the individual stimulants

Sources & further information

- Website: Reddit -r/stims

- Scientific article: Treatment of stimulant use disorder: A systematic review of reviews

- Opinion article: My adult ADHD drugs felt like a lifeline. Then came the scary side-effects

Disclaimer

The content available on this website is based on the author’s individual research, opinions, and personal experiences. It is intended solely for informational and entertainment purposes and does not constitute medical advice. The author does not endorse the use of supplements, pharmaceutical drugs, or hormones without the direct oversight of a qualified physician. People should never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something they have read on the internet.