Tianeptine is an atypical antidepressant. It is mood-brightening, activating, increases motivation, deepens emotions, and is a powerful anti-anxiety agent. Some people (ab)use it as a nootropic.

I discuss amineptine, a chemical cousin of tianeptine, here.

A brief history of humanity’s fondness for opioids

Humans have been using, or abusing, the molecular signature of pure bliss for a long time. Fossil evidence suggests that Neanderthals might have used opium seeds already 30.000 years ago. The first written text about opium dates back over 6000 years.

Opium seeds were also mentioned in the Odyssey: “Into the bowl in which their wine was mixed, she slipped a drug that had the power of robbing grief and anger of their sting and banishing all painful memories. No one who swallowed this dissolved in their wine could shed a single tear that day, even for the death of his mother or father, or if they put his brother or his own son to the sword and he were there to see it done…”

Opium seeds were described by Egyptians, Romans, and Greeks. It is thought that Egyptian pharaohs were entombed with them and they could be readily bought on the streets of Rome. Even Marcus Aurelius, the famous stoic, supposedly regularly enjoyed them. Thomas Jefferson supposedly cultivated poppy seeds in his garden.

Around 700 AD opium was traded all over Europe and Asia.

Galen (a Greek physician) and Paracelsus (“The dose makes the poison.”) each supposedly used (or abused) it. In fact, Paracelsus considered opium “the stone of immortality”.

During the opium wars, the British Empire secured the “right” to continue selling opium to the Chinese. At one point, it was thought that about 25% of the Chinese population was addicted to opium. Opium use was also widespread in Europe, and around 1850, British opium imports surpassed 150 tons per year and it is thought that parents were frequently using opium to placate crying children.

Opium use was also widespread in the US and between 1800-1900 its use was reportedly rampant as it was legal, cheap, and abundant.

From a leading US medical textbook (1880): “Opium causes a feeling of delicious ease and comfort, with an elevation of the whole moral and intellectual nature…There is not the same uncontrollable excitement as from alcohol, but an exaltation of our better mental qualities, a warmer glow of benevolence, a disposition to do great things, but nobly and beneficently, a higher devotional spirit, and withal a stronger self-reliance, and consciousness of power. Nor is this consciousness altogether mistaken. For the intellectual and imaginative faculties are raised to the highest point compatible with individual capacity…Opium seems to make the individual, for a time, a better and greater man.”

In 1898 the German pharmaceutical manufacturer Bayer synthesized diacetyl-morphine. This substance was soon accepted by the medical establishment for its ability to banish pain and induce euphoria with minimal interference on cognition, sensation, or motor skills. Diacetyl-morphine became later known as heroin.

Eventually, people figured out that it was addictive and Bayer, which now focused on aspirin, was pressed to halt production, which it did. From 1920 onwards, heroin became illegal throughout most of the Western world but it continues to temporarily “enhance”, and ultimately ruin countless lives today because “being wrapped in God’s warmest blanket” feels great…but is also highly addictive and financially ruinous.

Opioids produce a strong tolerance and users eventually increase their daily dose many times, sometimes by up to 100 times if financial resources permit. However, because financial resources often do not permit, people frequently rely on stealing. In fact, the term “junkie” was coined to name people that steal junk metal to finance their drug use.

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

Personal experience

I have experimented with low doses of tianeptine (12.5mg) a handful of times. Whenever I took it, it boosted my energy levels & mood, increased my motivation to do things, gave me slight euphoria, and made me “present” and at ease with myself and my surroundings. I was tempted to experiment with higher doses, though out of caution I did not because I was scared off by anecdotes of people who did (Reddit: r/quittingtianeptine). I have also heard of people getting heavily addicted to kratom, which bears decent similarities to tianeptine.

I am quite sensitive when it comes to noticing deviations from my normal baseline state, and even a single dose of tianeptine caused very mild withdrawal symptoms, primarily characterized by mild dysphoria. I am all about baseline energy and mood, and like other stimulants, tianeptine was not helpful in improving it, it was quite the opposite.

Anecdote time: A psychiatrist friend of mine prescribed tianeptine to a patient who has tried every other antidepressant under the sun in various combinations. Using his words, tianeptine “cured” her and allowed her to come off the other psychiatric drugs she was on (psychiatrists love polypharmacy). However, I have not followed up on whether she is still “cured”. Often in psychiatry people are just “cured” temporarily.

Of note, as an experiment, I also temporarily blocked my opioid receptors with naltrexone, which has taught me that a life without endogenous opioid signaling is barely worth living. I discuss my experience in more detail here.

How it works

Once upon a time, it was thought that tianeptine would act as a “selective serotonin reuptake enhancer” (SSRE). The paper proposing this mechanism of action was published long before someone had the “brilliant” idea of properly assaying the drug (i.e., figuring out to what receptors it binds and how strongly).

Even though some former heroin users had long claimed that tianeptine is an opioid based on how it makes them feel, it took a long time to show that tianeptine is indeed a mu-opioid receptor agonist (explained shortly). The term SSRE died as fast as it was born.

Tianeptine’s affinity for the mu-receptor is quite weak. Furthermore, tianeptine’s opioid activity is atypical, evidenced by the fact that it does not cause respiratory depression even at higher doses.

At therapeutic doses, the activation of the mu-receptor causes a downstream release of a variety of other neurotransmitters, including glutamate, dopamine, serotonin, noradrenaline, and histamine. This, coupled with the slight pleasure reaction tianeptine causes, increases motivation, drive, alertness, and emotions.

Opiates differ from substances like alcohol and weed in that they don’t significantly impair cognitive function, sensory perception, and motor coordination. In modest amounts, opiates can even have a stimulating effect.

Because of these effects, some people (ab)use tianeptine for its anti-anxiety, stimulant, and nootropic effects on an as-needed basis, others abuse it recreationally. If used in recreational doses, tianeptine is incredibly addictive, tolerance develops rapidly, and stopping the drug leads to nasty dysphoric withdrawals.

If given as an antidepressant, tianeptine is usually administered at a dosage of 12.5mg taken three times per day. Like other antidepressants, tianeptine’s antidepressant effect hinges on downstream adaptations both between and within neurons occurring over a period of several weeks.

The phrase “cold turkey” comes from the fact that during opioid withdrawal people develop goosebumps. Cold-turkeying opioids is incredibly hard & aversive – sometimes users feel raw physical pain.

Opioid signaling 101

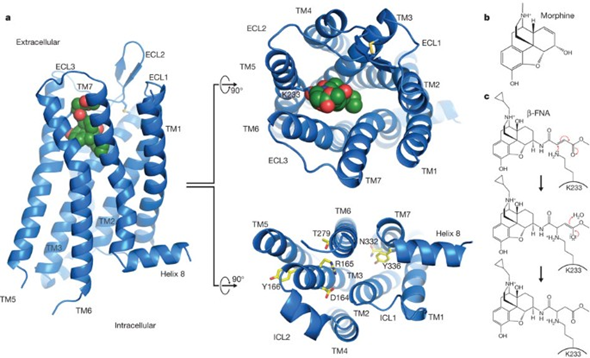

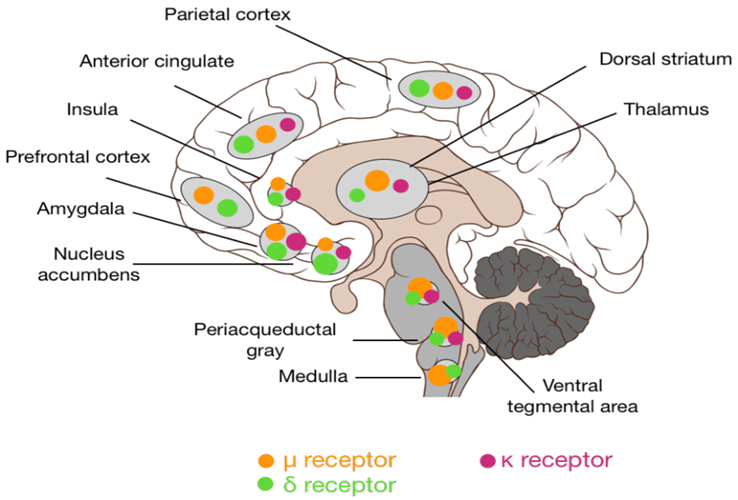

Opioid signaling in the nucleus accumbens shell, the brain’s major “hedonic hotspot”, mediates the feeling of pure pleasure – whether it is pleasure from sex, chocolate, or warmth. The specific opioid receptor mediating the molecular signature of pure bliss is the infamous mu-opioid receptor, which is the target of oxycodone, heroin, and other opioid drugs.

However, if somebody takes tianeptine (or injects heroin), the mu-opioid receptor is not only activated in the nucleus accumbens shell (the brain region where “pure pleasure” originates from) but all other mu-opioid receptors throughout the body are activated as well.

For example, this includes the mu-opioid receptors used in pain transmission pathways (leading to pain relief), the medullary breathing centers (leading to respiratory depression), and the mu-opioid receptors in the gastrointestinal tract (leading to constipation).

Under physiological conditions, opioid signaling in one region (e.g., the reward pathways in the nucleus accumbens shell, pain transmission, the breathing centers in the medulla, and the opioid receptors in the gastrointestinal tract) happens independently of opioid signaling in any other region.

But when a molecule is put into the bloodstream that has an affinity for these receptors, all of these formerly independent regions are activated in one go.

There are many different independent opioid systems distributed throughout the human body, in which the expression of opioid receptors serves to transmit inhibitory signals for a variety of functions. All opioid receptors are coupled to the Gi-pathway of GPCR signaling.

For example:

- mediating the feeling of reward (“pure pleasure”) in the nucleus accumbens shell

- inhibiting pain transmission (hence the use of opioids as pain medications)

- regulating gastrointestinal motility (hence constipation for opioid users)

- hypothalamic signaling (hence the decrease in testosterone with opioid addiction – or addiction to THC)

- regulating breathing (hence the respiratory depression that often ends deadly)

- the cough reflex (codeine is the prototypical antitussive agent)

- regulating the immune system

- regulating a variety of brain functions

I will limit my further discussion to the involvement of opioids in the “pleasure” response.

The major receptor involved is the infamous mu-opioid receptor. Over 100 polymorphisms are known in the mu-opioid receptor gene.

Selective mu-opioid agonists, such as endorphin, heroin, oxycodone, or morphine, typically induce euphoria, whereas selective kappa agonists, such as dynorphin, typically induce dysphoria. A cruel negative feedback loop exists between the kappa- and mu-opioid systems. If the kappa system is activated (e.g., by strenuous exercise) the mu-opioid system is upregulated, and vice versa.

Mu-agonists produce euphoria/pleasure and kappa-agonists produce dysphoria/malaise. A synthetic kappa-receptor antagonist with the name aticaprant is in Phase III development for MDD.

The acute effects of mu-opioid agonists can seem magical. Users feel well – sometimes for the first time in their lives. However, with prolonged use, insidious counterregulatory mechanisms kick in.

Among other things, the baseline mu-opioid signaling downregulates, and the kappa-opioid system upregulates. Hence, users feel dysphoric whenever they do not use opioids. Addicts say that simply wanting to relieve the negative state is as much a motivation to keep going as is chasing the high.

The well-known cycle of addiction starts and often ends deadly. In the process, exogenous opioid users cause immense suffering to themselves, their friends and family, and society at large. I believe that it is good that these drugs are banned or at least heavily regulated almost everywhere on Earth as opioids directly hijack the hedonic hotspots within the brain’s reward system.

Nonetheless, weaker opioidergic drugs such as tianeptine, buprenorphine, or tramadol can be useful for select cases of treatment-resistant depression – at least for a short period of time until desensitization and counterregulation set in.

However, using opioidergic drugs therapeutically in depressed individuals has considerable risks and downsides, especially the addictiveness.

Therefore, when it comes to the treatment of depression, the opioid system has been left mostly untouched –even more so than the dopaminergic system, which is the other neglected transmitter system pertaining to well-being (and not just the elimination of misery).

An often-abused indirect opioidergic drug is the cannabinoid THC, which I discus here.

Recently, ACKR3, a chemokine receptor that functions as a scavenger for opioids has been identified. Inhibiting this receptor would elevate synaptic opioid levels in an analogous way an SSRI elevates synaptic serotonin levels. Inhibitors are currently in clinical trials for opioid use disorder….and may one day be available for “life enrichment” purposes.

Addiction potential

After trying opioids, a lot of people think “Why try hard at life if I can have it directly?” Well, one can have it directly – but only for a (very) limited amount of time until massive counterregulation sets in.

If used at low therapeutic doses and on an as-needed basis, tianeptine is not overly addictive. However, for many, it does not stay in the “I use it only on an as-needed basis” category for long. Anecdotally, many end up dose-escalating into oblivion winding up with a full-blown addiction that is incredibly hard to beat. There is even its own Reddit group for people dealing with tianeptine addiction (r/quittingtianeptine).

Opioids in the treatment of depression

Opioids are directly activating the endogenous reward system. Furthermore, opioids do not just have physical pain-killing properties but are also excellent emotional painkillers.

Weak opioidergic drugs, such as buprenorphine, tramadol, or tianeptine, can be useful for select cases of treatment-resistant depression.

When it comes to the treatment of depression, understandably, the opioid system has thus far been left mostly untouched – more so than the dopaminergic system, which is the other neglected transmitter system pertaining to well-being and not just the elimination of misery.

As David Pearce points out, using opioidergic drugs (“pure pleasure”) therapeutically in depressed individuals represents an ethical and legal minefield, since they can have great therapeutic effects on one side but are incredibly addictive and hard to withdraw on the other.

However, for a short period of time and until desensitization & counterregulation set in, opioids are incredibly effective at treating depression.

The opioid crisis

The US opioid crisis is not a recent development but has possibly been going on ever since oxycodone was released in 1996. Oxycodone was marketed to be much less addictive than other opioids because of two things.

- Firstly, the drug was designed with an extended-release effect (which could be circumvented if the pills were crushed).

- Secondly, doctors were made to believe that it is weaker than morphine (but, it is actually stronger).

Doctors started to widely prescribe it, and because drug revenue is also a function of dose, they were “encouraged” to escalate the dose quickly. Consequently, a lot of people wound up being needlessly prescribed high doses of opioids for a variety of conditions.

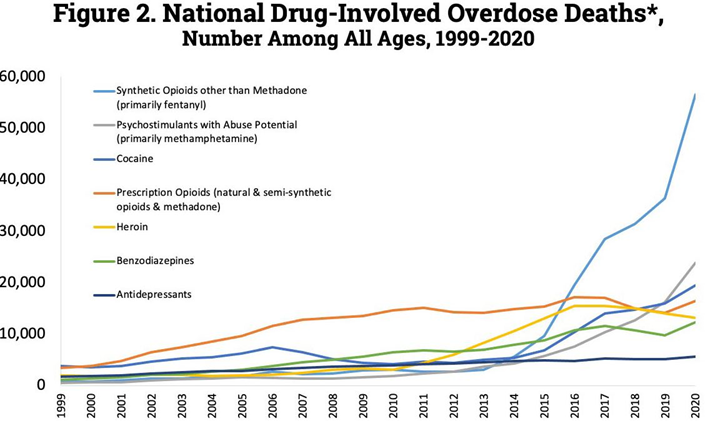

Patients started to widely abuse it and once enough people could no longer obtain a legal prescription, the fentanyl black market boomed.

Fentanyl overdose is currently the leading cause of death in the US for people below 45. It is in part because of this (i.e., “deaths of despair”), that the US is the only first-world country where the average lifespan is going down instead of up.

Hyper-capitalism coupled with a society that is wrong on many levels caused about 500.000 deaths from opioid overdoses in the last 25 years alone – and many more people still use these drugs every day. It is estimated that at least 2 Mio. Americans, a little less than 1 in 100 people, currently struggle with opioid (ab)use.

Kratom

I will briefly discuss kratom because it bears some similarities to tianeptine. Kratom has been used and abused for thousands of years for a number of reasons. Kratom is a tree (Mitragyna speciosa) native to Southeast Asia. Its leaves contain a variety of understudied alkaloids.

Some of these alkaloids, such as mitragynine, have been found to bind weakly and in a “dirty” manner to a host of different targets, including a complex modulation of the mu, delta, and kappa-opioid systems. Therefore, some people use kratom as an alternative to more traditional painkillers, and some speculate that it may be a potential way to help with coming off more potent opioids.

Similar to tianeptine, kratom has a range of effects, including pain relief, mood enhancement, stimulation at lower doses, and relaxation at higher doses.

Like with tianeptine, moderate occasional use (e.g., once or twice per week) is presumably fine but chronic use is devastating to the pleasure-pain balance and quickly leads to rapid dose escalation and addiction. There is also a Reddit group for people who are trying to kick kratom addiction (r/quittingkratom).

Interestingly, tianeptine is a common recreational drug in some parts of the US that have banned kratom, presumably because a lot of people switched to tianeptine after the ban on kratom.

Other experience reports

For a discussion of the molecular correlates of well-being, and links to accounts of various related molecules I have experimented with, read here.

For a full list of experience reports click here.

Sources & further information

- Scientific review: Reward processing by the opioid system in the brain

- Website: Wikipedia – Tianeptine

- Anecdotes: Reddit – r/quittingtianeptine

Disclaimer

The content available on this website is based on the author’s individual research, opinions, and personal experiences. It is intended solely for informational and entertainment purposes and does not constitute medical advice. The author does not endorse the use of supplements, pharmaceutical drugs, or hormones without the direct oversight of a qualified physician. People should never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something they have read on the internet.