Semaglutide, a GLP-1 agonist, is one of my favorite drugs. It was originally developed as an antidiabetic agent because GLP-1 amplifies glucose-induced insulin release. However, as its powerful weight-loss benefits became evident, which go far beyond simply reducing appetite and energy intake, trials for obesity started.

Lo and behold, at the highest dose, people lost about 18% of their body weight in the first year. It was soon patented as an anti-obesity drug. The anti-obesity drug.

It did not take awfully long before it started to be widely used (and abused) as a weight-loss agent, both on and off-label. Given that we have patient data on GLP-1 agonists since 2012, major negative unintended long-term side effects seem unlikely.

Next to their effect on appetite and weight control, GLP-1 agonists also seem to have some more widespread anti-addictive and anti-impulsive properties, presumably due to the way they affect the endogenous reward system. A friend of mine realized that after starting semaglutide he stopped buying lottery tickets.

I predict that in 10 years a double-digit percentage of the population will be on a GLP-1-agonist or analogous drugs (if the world as we know still exists by then, which is far from certain).

The reasons semaglutide is one of my favorite drugs are multiple:

- It is an awesome drug, and it helped me out a great deal.

- Hacking my appetite and weight improves my vitality and looks, both of which are crucial to my well-being.

- Taking semaglutide is like sending a constant satiety signal to my brain. By reducing appetite and therefore distractions, for me, semaglutide is useful for productivity and “nootropic” purposes.

- In the past, I struggled with getting lean and staying there. Consequently, a lot of my time & energy was wasted on thinking about food. Brainpower that could be used for other things, for example improving myself and the world.

It is no coincidence that many top performers use semaglutide, the best drug currently available to reduce the human natural tendency to overindulge.

Personal experience

In my early twenties, I spent one year in Canada. As with most other Europeans going overseas to North America, I gained an aesthetically unpleasant amount of fat. After coming back to Europe, I wanted to lose the fat I had gained.

Because of misleading online “advice”, I started intermittent fasting, and I also vastly underestimated my caloric needs. I lost a lot of weight much faster than I should have. As my body fat approached single digits (and my leptin levels presumably approached starvation territory), I went through a period of disordered eating. My baseline energy was non-existent, and I was constantly preoccupied with eating, not eating, and food-related planning.

Even long after recovery, I was still struggling with a lot of stubborn physiological and mental adaptations. I was always fatigued, I had problems with thermoregulation (especially heat intolerance), my hands and feet were mostly cold, my mood and libido were low, and I had developed stubborn hormonal problems.

Furthermore, not eating was a constant struggle and every day was a battle. I was always hungry and soon after eating, I was hungry again, no matter what I ate.

I always had to bring snacks with me because every hour or so I would get weak and ravenous if I did not eat – despite having been at a healthy level of body fat (about 12%) and a normal caloric intake (2500-3000kcal). To me, these adaptations were a heavy “biological shackle”, literally eating away at the enjoyment, efficacy, and efficiency of whatever I was doing.

After learning about semaglutide and its putative effects on POMC neurons, I was curious and I decided to try it (this was long before semaglutide became popular).

The time I started semaglutide -which is basically a “satiety signal” to the hypothalamus-, I won’t forget quite soon. The day after doing my first injection, I had a date. We said she would come over to my place and we would cook dinner. She came at around 7 pm, a time when I would normally be very hungry. This time I was not. We ended up talking until midnight, I just was not hungry. Furthermore, I did not get sleepy (and at the time, I normally got super sleepy by like 8–9 pm or so).

At midnight, we had a small yogurt with some berries…and I was satisfied. I was sitting there in disbelief. I had lost the feeling of true satiation a long time ago…now I was satisfied with a tiny 300kcal snack. We ended up talking until 4.30 am. Without semaglutide, the date would have gone much differently. This reminded me again how, for some of us, strong biological shackles bar us from living a normal, enjoyable life.

Before the semaglutide, I would always go for volume. However, now, eating big-ass salads like I had used to was literally painful. Now, I did not care about volume anymore at all. Also, within a few days, I stopped eating chocolate because semaglutide simply killed any cravings.

Before semaglutide, I had not experienced complete satiety for a couple of years and just accepted the constant low-level background hunger. Finally, a normal meal kept me satiated. I got still hungry if I did not eat but the “ravenous” hunger was gone.

I felt stupid for having tried all of these other things, including meditation to watch and accept my cravings, every macronutrient composition under the sun, and even talking it to death during psychotherapy.

Within days, many of my problems were a relic of the past. My resting heart rate increased from 45 bpm to 55 bpm (Note: Contrary to popular wisdom, a lower heart rate is not necessarily better -it is better if the lowering of the heart rate is driven by your heart getting stronger but not if it is driven by a reduction in sympathetic tone), my energy levels improved, and my cravings were crushed, but most importantly, I could again get into extended flow states without getting distracted by hunger. Within a month, my levels of testosterone, thyroid hormones, and cortisol normalized.

Semaglutide also increased my energy levels – particularly at the beginning. Before semaglutide, I usually got quite tired quite early at night (e.g., by 8 pm I would get super sleepy), which I suppose was a lingering adaptation to past “starvation”. Already in the first week, semaglutide reversed my weird advanced-shifted Circadian rhythm.

Similar to what people report after starting an antidepressant, after only a couple of weeks I had gotten used to my new state (never hungry), and my old state (always hungry) seemed like a distant dream – despite having been hungry for years. Now thinking back, I can hardly relate anymore.

As of the time of this writing, I have been on a low dose of semaglutide for about 2 years. I now have few dietary rules and restrictions, and I can have my cake and eat it too. Literally. Semaglutide changed my life for the positive, and I am indebted to whoever initiated the development of GLP-1-agonists.

Initially, there was some slight nausea in the morning. In my first month, I also lost some weight, which I counteracted by vastly increasing my caloric intake. Interestingly, without changing my exercise (about 1h every day), I now needed to eat about 500-1000 kcal more than before to maintain the same weight.

The only sustained “side effect” I have noticed is a reduced pleasure from food, probably because GLP-1 agonists not only help with the homeostatic aspects of feeding but also reduce the hedonic aspects of it (as discussed shortly). However, for me, this is hardly a “side effect”.

The major downside of being on GLP-1 agonists is the need to watch my caloric intake closely as due to the immutable laws of thermodynamics, over the long run, my body can only give out what I put in. Unfortunately, getting in the 3500kcal I need is not on the cards if I do not count, or at least ballpark, my calories. Adding lots of olive oil to my Huel shakes helps a lot. I discuss my diet in more detail here.

I have experimented with GLP-1 agonists across the whole dose range, including a short amount of time on the full 2.4mg per week. After experimenting with metreleptin, I decreased my dosage to 0.1mg per week split into multiple doses (1 click per day). Any more than that made it impossible to eat a sufficient number of calories. Because I do not mind injections, I administer semaglutide every day or every other day for plasma levels to be more stable compared to the usual once-weekly administration.

I have always had a big appetite and thinking about food was a constant in my life (even in my teens). I find hunger incredibly distracting, and it kills my flow states. With semaglutide, I rarely think about food and I only ever get hungry when I am really hungry. With the semaglutide, I do not think about food at all. No background hunger. Regardless of all the other benefits, for me, this is gold, because combined with a good meal plan (macros, food, timing), I am not bothered by this animalian drive anymore.

In my opinion, this makes me more “human” because my mind can bother about much more “human” things. I still love eating good food, going out to restaurants, etc. but I want to be in charge of it and not my appetite.

In my opinion, constantly having to think about food is an inhuman state to live in because as a human being, I am more than just about satisfying my hypothalamic drives (or at least I like to think so).

Some researchers think that semaglutide is “unhealthy” (e.g., because it increases heart rate). For me on a low dose of semaglutide I rarely think about food. I have no cravings and consequently, my food choices are much better. Automatically. The 2nd and 3rd order effects of this (such as reduced body fat, better metabolic health, more stable blood sugar, and better productivity) presumably vastly outweigh any risks and side effects from semaglutide itself.

Update: After having been on a low dose of semaglutide for 3 years, a couple of months ago, I came off it. I am currently trying to gain weight, which semaglutide makes impossible to do. Interestingly, for some reason, my appetite is now vastly lower than before the semaglutide, hinting at the possibility that all this time on semaglutide led to some favorable rewiring of my appetite centers.

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

Microdosing semaglutide

I personally know roughly a dozen people who have had success with microdosing semaglutide. Pretty much everyone, my past self included, has used it effectively for getting and staying lean.

Doses were/are usually in the 0.1mg-0.25mg/week range. Also, most people have greater success with dosing at least three times per week, which keeps plasma levels more stable.

In my country, an Ozempic pen containing 4mg of semaglutide roughly costs 150 Euro. With a dosage of 0.1mg per week (equaling 1 click per day), which is the dosage I have used, a single pen lasts for 40 weeks, amounting to roughly 50c per day. Furthermore, I and others find that at these dosages there are no unwanted side effects, other than appetite suppression and perhaps the need to count calories to not go below an unwise minimum.

A note on biological self-improvement

Semaglutide has done more for my self-improvement than psychotherapy + meditation combined. Outsourcing my hunger to semaglutide + Huel shakes was worth a lot to me.

After starting semaglutide, a lot of other things improved. Overall, and as a direct consequence of nuking “background hunger”, it increased my mindfulness, made me more fun to be around, and made me a better listener. Also, soon after starting it, I met my current girlfriend. Our dates would surely have gone differently had I not been on it.

My experience with semaglutide made me realize once again the power of biological shackles and what can happen if they are removed.

Even more so than depression or anxiety, constant hunger is mostly a biological problem. Given the right lever is pulled, biological problems can be eliminated in the same way a computer bug can be eliminated with the right programming.

Case report – Semaglutide for binge eating

A friend effectively cured her binge eating disorder using semaglutide. I discuss the case in more detail here.

How it works

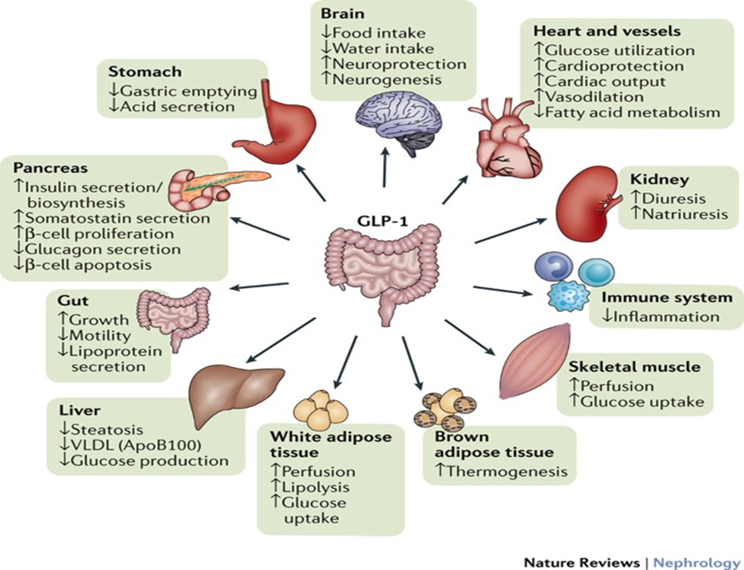

Semaglutide mimics the action of GLP-1. GLP-1 is a peripheral satiety peptide that is secreted in the gut in response to carbohydrate intake. GLP-1 has a range of functions. It improves insulin release, boosts insulin sensitivity, delays stomach emptying, and enhances beta-cell function.

Endogenous GLP-1 has a half-life of around 5-10 minutes but semaglutide has been modified to have a half-life of around 4-7 days.

Even though semaglutide has a lot of peripheral actions that contribute to its effects (e.g., delayed stomach emptying, an incretin-potentiated insulin release), its power is presumably mostly due to its action in the central nervous system, where it has a variety of effects on multiple aspects of neuroendocrine, autonomic, and hedonic control.

GLP-1 receptors are present at multiple sites in the central nervous system, where GLP-1 acts as an independent local neuropeptide. This means, that GLP-1 signaling in the gut is mostly uncoupled from GLP-1 signaling in the brain. However, if semaglutide is administered, all of the tissues expressing GLP-1 receptors are modulated in one go.

In the brain, these regions include:

- brain stem sites, which are thought to modulate sympathetic nervous system activity as well as feeding

- multiple regions in the hypothalamus, in particular POM-C neurons, which modulate feeding, energy expenditure, activity levels, and hormone release

- multiple regions of the mesolimbic reward system, including dopamine-producing neurons of the VTA, a subset of neurons in the nucleus accumbens, and a region of the lateral septum.

The two prominent therapeutic effects are firstly, satiety & energy expenditure, and secondly, the reward system. Interestingly, the administration of GLP-1 seems to have “anti-addiction” effects not just in relation to food but also extending to drugs of abuse, such as cocaine, amphetamine, and alcohol.

Semaglutide is also a potent sympathomimetic agent. For example, on my first day of semaglutide, my heart rate shot up by ten points, and my heart rate variability (HRV) was crushed (however, over the course of a couple of months, both returned to almost normal). Furthermore, I felt a charge of energy.

As a sympathomimetic agent, semaglutide is a potent stimulant of sympathetic nervous system activity, and it may be in part due to this effect that semaglutide is such an amazing fat-loss drug. Adipose tissue is densely innervated by the sympathetic nervous system and signaling through adrenergic receptors mediates lipolysis (as well as appetite suppression), which is readily apparent with amphetamines (indirect sympathomimetics) and clenbuterol (a direct beta-2 receptor agonist). Though, in contrast to these, semaglutide shows little to no tolerance buildup, presumably because it is a hormone, and hormones have little tolerance buildup in general.

In my opinion, weight loss with semaglutide is healthier (and more sustainable) compared to natural weight loss, in part because counterregulatory mechanisms such as increased hunger, low energy, and alterations in hormone secretion are not set in motion – or at least not as much. I discuss this in more detail here: Why Weight Loss is Not About Calories In vs. Calories Out

Furthermore, preliminary evidence indicates that semaglutide protects against cardiovascular events (heart attack, stroke) and neurocognitive decline (dementia). However, how much of this is related to weight reduction and an improvement in metabolic health, or something different altogether, is currently unknown.

Tirzepatide, a dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist, seems to outperform semaglutide. However, in contrast to GLP-1 agonists (for which we have human data spanning over a decade), there is no long-term data on GIP-agonists.

GLP-1 agonists as anti-addiction drugs

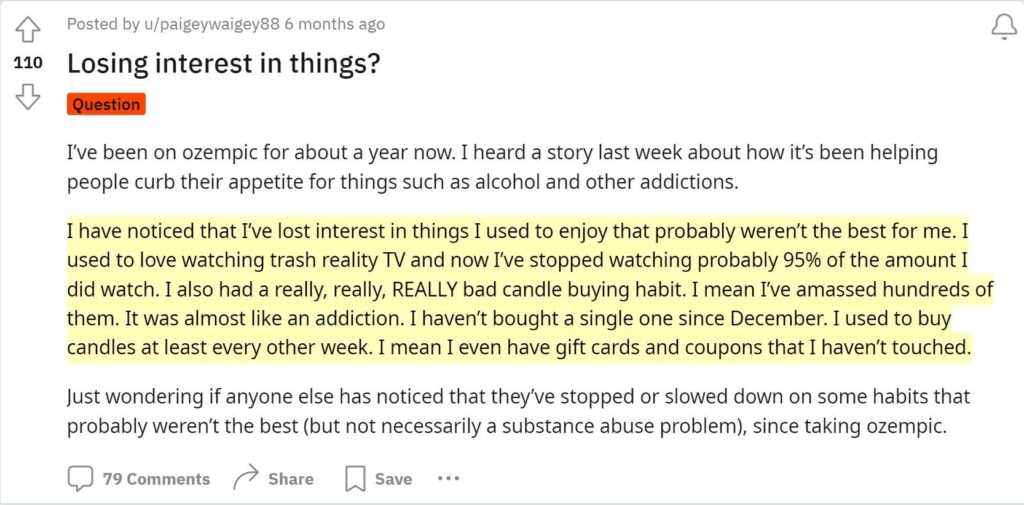

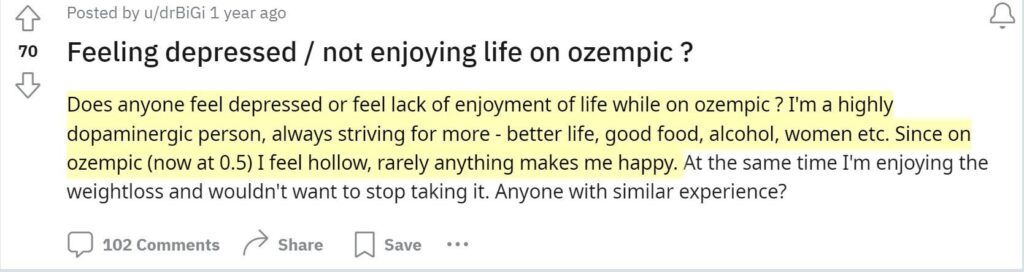

As discussed above, GLP-1 receptors are found on dopaminergic midbrain neurons. Through their effect on dopamine, GLP-1 agonists seem to lessen all kinds of impulses – far beyond food-related thoughts and behaviors.

One friend, who is into buying lottery tickets, realized that he had rarely bought lottery tickets since starting Ozempic. For some people, a reduction in impulses is good for mental health (particularly for chemical and behavioral addictions), which often take a mental toll and reduce self-worth.

For others, GLP-1 agonists can cause anticipatory anhedonia (a loss of interest in things) and depression.

As always, biological intervention is a calculation of trade-offs.

Are GLP-1 agonists “unhealthy”?

Some people think that GLP-1 agonists are “unhealthy” to take, in part because they elevate heart rate and reduce heart rate variability. Even if the drug itself were unhealthy (which we have little reason to believe if an individual counteracts the possible loss of lean body mass by engaging in resistance exercise), the second-order consequences of the drug, particularly weight loss and making healthier food choices, would, in my opinion, easily outweigh the direct unhealthiness of the drug.

Whether the drug is net “unhealthy” for people such as me who are already lean and following a healthy diet is currently unknown (and we will presumably never have a clear-cut answer to this question other than anecdotal “evidence” and case reports).

However, even if GLP-1 agonists were unhealthy, I would still continue to take them because I love the mental freedom from food-related thoughts they provide. As always in life, the upsides and downsides of doing something need to be weighed against the upsides and downsides of not doing this particular thing.

The importance of body fat

For me, the introduction of semaglutide into my system eliminated that hard-to-fight urge to constantly eat. The feeling of true satiety, which I had not experienced in a long time, became my new normal state (and I soon got used to it).

Initially, I lost some weight, but as my body fat approached single digits, the feeling of hunger and weakness returned. Even though a small meal would now satiate me quite quickly because of semaglutide, I nonetheless got hungry quite soon after eating. Self-experiments with metreleptin have shown me that this was due to low leptin levels.

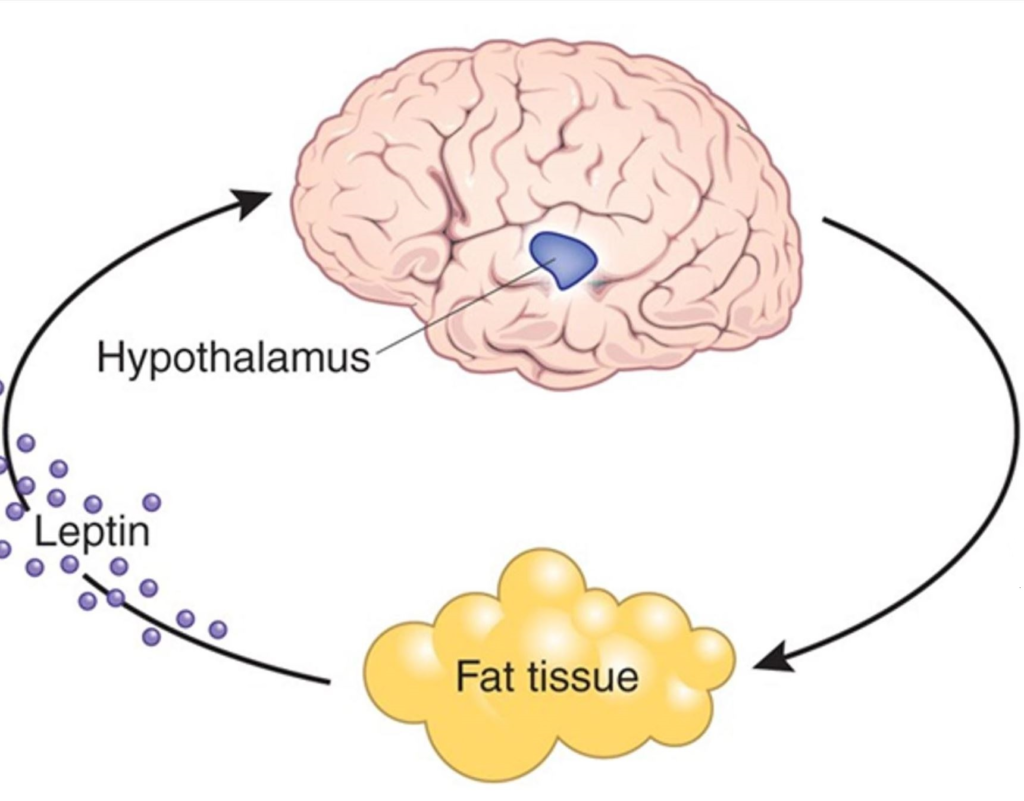

It seems that leptin has a permissive effect on semaglutide action, meaning that if leptin levels are too low, semaglutide does not work properly. The reason is probably that leptin signaling is coupled to a cytokine receptor (STAT3 signaling) paving the way for POMC neuron activity whereas semaglutide signaling is only coupled to a measly GPCR receptor.

Weight and appetite regulation are based on two things:

#1: Energy intake

When energy intake remains below caloric needs, weight-gain-favoring adaptations occur. Energy levels, mood, sex drive, satiety, etc. all take a hit – regardless of body fat levels. Caloric intake is signaled to the hypothalamus by a plethora of mechanisms. These include satiety-peptides (GLP-1, CCK, PYY, PPY), insulin, vagal nerve endings from the gut, stomach stretch, and even hypothalamic receptors for glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids. GLP-1 agonists can partially hack this (which is why they are so effective for weight loss), meaning that GLP-1 agonists mimic “food abundance”.

#2: Body fat

When levels of body fat are low (individuals vary with regard to what “too low” means), adaptations to starvation will be set in motion regardless of energy intake. This is single-handedly signaled by the adipokine leptin, which is secreted by adipose tissue in proportion to how “full” an adipose cell is. This means that if body fat levels (more specifically, leptin levels) are below a certain threshold, the rest of the satiety system ceases to work properly. Unbeknownst to many, the effects of leptin go far beyond appetite regulation. I discuss leptin in more detail here.

Therefore, as a member of Homo sapiens, I have to accept that my body fat levels must not be too low and, other than through the administration of a leptin analog, there is no way to circumvent this – at least if vitality and mental sanity are a priority.

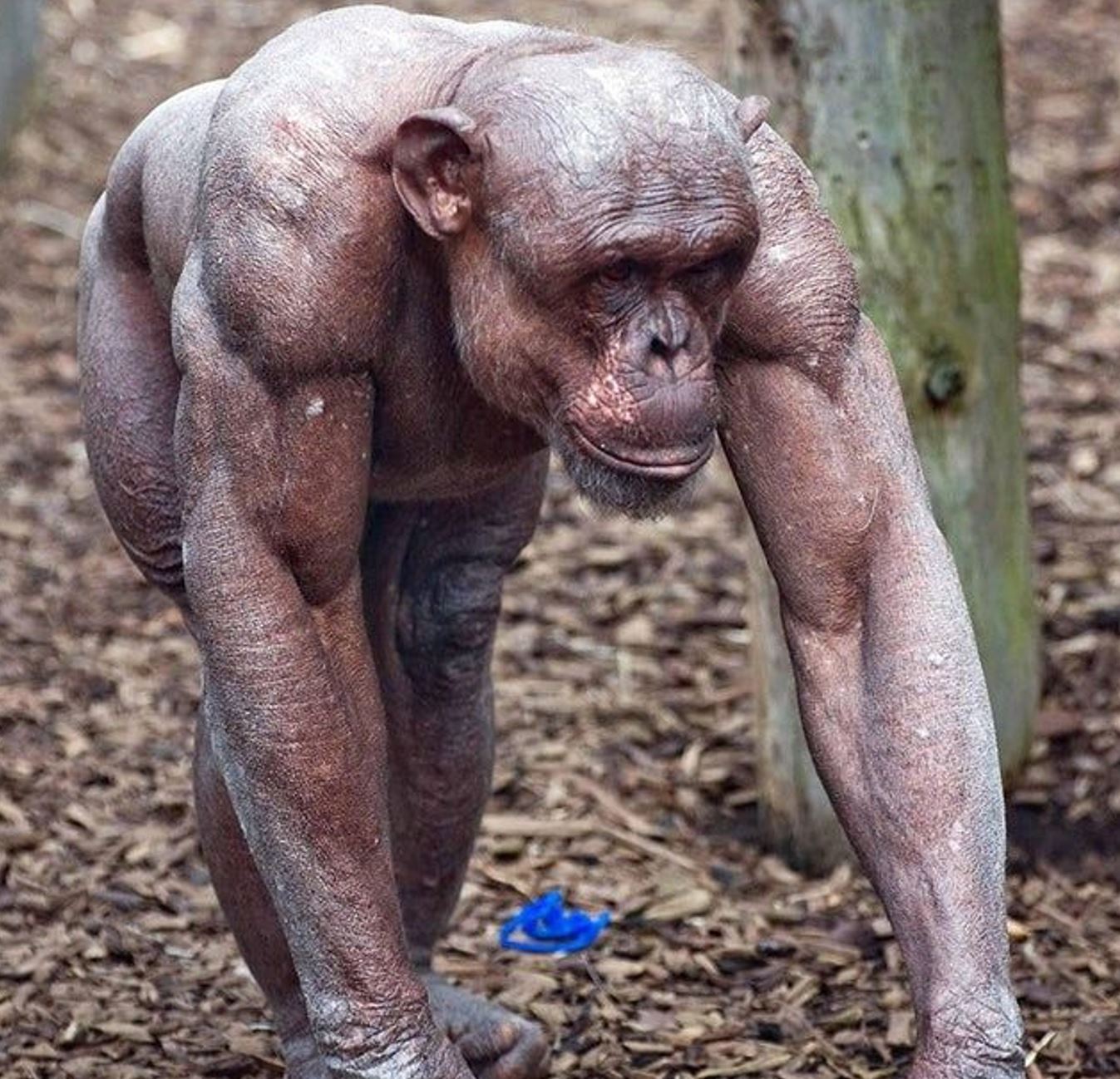

The human body evolved a mechanism that stops working properly if adipose tissue reserves are too low, presumably for survival-related reasons. However, purely from a functional perspective, there is little reason to assume that humans need to carry more fat than the closely related chimpanzees.

A brief note on evolutionary biology

When I was a child, I imagined archetypal nature to be this caring, nursing mother. However, as I learned more about the world, it turned out that romantic Mother Nature is rather cruel and callous. The Earth’s biosphere in its original state is incapable of supporting human flourishing as it is naturally infested with predators, parasites, food scarcity, and a variety of diseases.

Given that this was the evolutionary backdrop against which my ancestors’ bodies and minds developed, I now find myself in an utterly unnatural environment. In the same way that humans invented technologies to tailor the biosphere to human flourishing, I can use technologies (e.g., pharmacology) to update my body and mind to the contingencies of the modern world.

For example, in the past, food was usually quite scarce and therefore, my ancestors evolved to be drawn to junk food, overeating, and storing fat. However, this is maladaptive in the modern-day environment. The fact that modern food has been engineered to trigger overconsumption surely does not help either (sweetness; umami; mouthfeel; caloric density; flavorings; crunchiness; etc.).

My primitive brain is therefore mismatched to this modern ecosystem of convenience and abundance and an orchestra of mechanisms wants me to pig out. For many members of my species, food addiction, obesity, type II diabetes, and cardiovascular disease are a consequence.

I use GLP-1-agonists to modify the homeostatic and hedonic aspects of feeding and, in my opinion, using this technology is only as artificial as living in the modern world in the first place.

This also makes me wonder whether we humans are generally unfit for the future in the same way our “thrifty genes” are unfit for the present. Fortunately, the ability to discover and use explanatory knowledge (a.k.a. science) gives us humans the power to transform nature and ourselves – limited only by the laws of the universe.

Other experience reports

For a full list of experience reports click here.

Sources & further information

- Scientific review: Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity

- Scientific review: Tirzepatide versus Semaglutide Once Weekly in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes

- Anecdotes: Reddit – r/semaglutide

Disclaimer

The content available on this website is based on the author’s individual research, opinions, and personal experiences. It is intended solely for informational and entertainment purposes and does not constitute medical advice. The author does not endorse the use of supplements, pharmaceutical drugs, or hormones without the direct oversight of a qualified physician. People should never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something they have read on the internet.