Over the past couple of months, I also met a couple of other individuals who had their lives yanked away from them by Long-COVID. One guy used to be a semi-professional cyclist. Three years after, he can hardly do any exercise. He is back to 80% but he still gets the occasional crashes. According to him, making it through Long-COVID without going insane is the accomplishment he is most proud of.

Another guy I know had to quit his high-paying job at the consulting firm McKinsey after having taken sick leave for half a year. His girlfriend left him, and he now sits around doing nothing. His vitality has taken a huge hit with a massive fallout on every domain of his life, including relationships, work, and mental health. Understandably, he is now also depressed.

Long-COVID Case Report

One of my best friends had gotten Long-COVID after his third COVID-19 infection. He was enjoying his life in Bali at the time. He had to pay 8000 euros out of pocket for a private Bali hospital stay for pretty much nothing. After a chaotic flight back in a wheelchair he moved back in with his parents and was housebound. Back then he could go for a single short walk around the block (but only on his good days). On his bad days, he was physically, cognitively, and emotionally wrecked and just lay around with brain fog.

For months, he slept 12-15 hours per day, had post-exertional malaise (energy crashes after increased activity), and had a host of psychiatric symptoms he never had before.

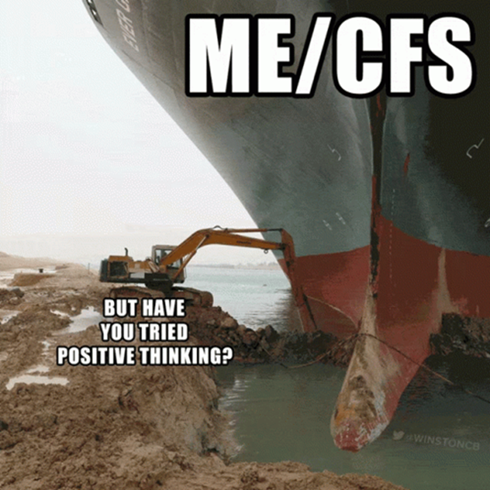

Interestingly, he was now also prone to bouts of anxiety, which he had never been before. He is the type of guy who goes out to the city and comes back home with three phone numbers from women he randomly approached on the street. Now he gets anxious when he is standing in the supermarket (which he rarely went to though). Often, he also got anxious and panicky before friends visited him and he usually kept visits to once per week only and only one person at a time. This heightened state of anxiety seems to be a common theme in the Long-COVID and ME/CFS community.

As he is one of my best friends, I wanted to help him but I could not, which made me feel quite helpless. Given that scientific progress was incredibly slow and nobody pretty much knew anything, I had to reason from scientific first principles and what was known at the time. We took matters into our own hands and after 4 months we started to experiment heavily.

Initially, our experiments were quite light but as time went on, we got more aggressive. The more aggressive we got, the better he got. Hard to say whether our experiments were causally related to his improvement – he thinks without a doubt.

Now, 18 months after getting the condition, he is back to resistance training and cardio. After 12 months, he approached 80-90% in everyday life but did not dare to exercise. Now, 18 months after, he is back to 100% in everyday life and roughly at 80% during exercise (hard to say though whether the exercise impairments are just due to the long period of inactivity). He is currently training for an Ironman, 21 months after getting long COVID.

Interventions with comments on what he thinks how important the intervention was:

- Pacing: He needed to avoid “crashes” at all cost. Thus, pacing himself was one of the most important aspects. Sometimes, he crashed for weeks after a single exertional event – particularly physically exertional things (such as going for a brisk walk). He also withdrew from stuff that was emotionally taxing (incl. meeting with friends if he did not feel like it). To make pacing easier, he took 10-20mg of propranolol (an unselective beta blocker that also penetrates the blood brain barrier) every day– bringing down both emotional as well as physical exertion. On his bad days and weeks, he also used benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines brought down the anxiety and panic. While not optimal, our reasoning was that benzodiazepines are much less harmful than a crash. A lot of people were made worse (sometimes permanently) because their doctor thought that “graded exercise therapy” was a good idea.

- SSRIs: After starting escitalopram (gradual increase from 1.25mg to 10mg per day over the course of 1 month), things seemed to get better. The anxiety and panic were lessened and he had to use benzodiazepines much less. There is also quite a bit of evidence that SSRIs help long-COVID symptoms. He is taking 5mg of escitalopram to this day. In his opinion, SSRIs were a key aspect in helping him recover (whether that is true or not is hard to say). I discuss my experience with SSRIs here.

- Ketogenic diet: There is preliminary evidence that autophagy improves ME/CFS symptoms. A ketogenic diet gives about 70% of the autophagy benefits of a pure water fast (as insulin & IGF-1 levels are brought down to very low levels). He used a low dose of an SGLT-2 inhibitor (dapagliflozin 2.5mg) to make the ketogenic diet “easier” and more effective. Without the SGLT-2 inhibitors he was unable to reach ketosis for some reason, perhaps because he was so physically inactive at the time (which is terrible for insulin sensitivity). Theoretically, SGLT-2 inhibitors are contraindicated with a ketogenic diet but I feel combining them is perfectly fine if you know what you are doing. We just measured his blood ketone levels with urine sticks twice per day. Of note, supplementing with ketone esters is not even close to the same thing. It is not about ketosis per se but about the cellular adaptations (gene expression changes) associated with ketosis and plasma ketone levels are only a proxy for this. My experience with the ketogenic diet here.

- Fasting: He also did several 36h fasts, 72h fasts, and 5 day fasting mimicking diets. On fasting days, we stopped the SGLT-2 inhibitors. During times he did a lot of fasting, he got noticeably better. To make the fasting easier (without detracting from its effectiveness) he ate a lot of spinach and mushrooms and other very low-calorie foods that are filling up via volume. We did not do this all at once. We started with a ketogenic diet, after a couple of weeks we added the SGLT-2 inhibitors, and after 1-2 months we added the fasts. He is now back to a normal liberal diet (i.e., not watching his diet). Fasting is discussed here. My experience with fasting here.

- Everolimus: Right at the beginning we added 5mg of everolimus once weekly. Already after his first dose he could feel that something is slightly different (placebo?). This was one of our first interventions and he is taking the everolimus to this day (technically, he is currently taking rapamycin because of price and availability). We chose everolimus over sirolimus (rapamycin) because everolimus has a higher blood-brain barrier penetration. There is scientific evidence that anti-aging folks who have taken rapamycin before, during, and after a COVID infection have much lower rates of long COVID and their COVID cases are much milder in general. As an mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin leads to widespread changes in gene expression, downregulates the immune system, and reduces sterile inflammation. Inflammation is probably a key aspect of long COVID, particularly neuroinflammation.

- Valacyclovir: He used 1g/d of valacyclovir throughout (1 year in total). The idea is that ME/CFS is associated with the reactivation of herpes retroviruses (particularly EBV), and that this makes the neuroinflammation worse. Hard to say whether it helped or not. Of note, antivirals help some people with ME/CFS but not others.

- Ibuprofen: For a couple of months, he used daily ibuprofen (around 800mg per day). NSAIDs inhibit COX enzymes, which reduces levels of inflammation. He also used esomeprazole to prevent stomach ulcers. Celecoxib (COX-2 selective) would be a better choice because the risk of stomach ulcers is much lower and thus it does not need to be combined with a proton pump inhibitor.

- Metformin: The idea was to reduce levels of inflammation. He used 500mg twice daily for half a year.

- Ketamine: We did biweekly subQ injections of ketamine with a dosage of 0.5mg/kg. Ketamine increases neuroplasticity and reduces neuroinflammation. Frequent use is probably more neurotoxic than most people appreciate (discussed here), even at low doses. Nonetheless, we judged the effort-reward ratio to be favorable. Furthermore, he had been living without any form of excitement and pleasure for so long and the ketamine sessions gave him a much-needed emotional release. He did about 10-15 sessions in total.

- LDN: Low-dose naltrexone was a dead end. The initial week of anhedonia (naltrexone blocks the mu-opioid receptor – in other words, it is an “anti-opioid”) was highly uncomfortable. After 2-3 months he just stopped taking it because he felt like it did not do anything. This was also one of our first interventions because we judged the risk to be very low – but, as so often, so is the reward.

He claims that he could “feel” that every single interventions outlined above made him a tad better (other than the naltrexone). For most interventions, he could feel the changes quite fast (days to weeks). He had a couple of small setbacks associated with minor and major crashes. Initially (only taking low-dose naltrexone + everolimus) we did not know whether he is improving at all. However, he also did not seem to get much worse and so we stuck with everything and always thought about add-ons and improvements.

This protocol is quite extensive, aggressive, and not for the faint-hearted. However, in my opinion, it touches many different angles that may be etiologically related to the development and persistence of long-COVID. We argued that the risks associated with this protocol are less than the risks of doing nothing.

Anyway, he is mostly back to normal now and has his old life back. He is exercising again, leading his small company, and leisure travels quite a bit.

Whether the self-experiments were the cause of his getting better or whether he would have gotten better anyway on his own is impossible to tell. However, the temporal correlation and the fairly rapid improvement (months) suggest a causal relationship. At the very least we can say that the experiments have not prevented a recovery from happening and no interventions seem to have made him worse.

For most people, things get eventually better but the time to recovery can range from months to years.

How does Long-COVID develop?

Short answer: Nobody knows.

It seems though that short of pulmonary symptoms, Long-COVID is potentially identical to chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), which frequently (always?) starts after a viral infection, particularly Epstein bar virus (EBV), though a number of other viruses have been implicated to cause a similar syndrome.

Patients report fatigue, “brain fog”, headache, autonomic dysfunction (particularly issues with low blood pressure), and a host of neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as depersonalization, anxiety, and depression. Many also report that their limbs feel “heavy”. Many also have a much higher heart rate than before.

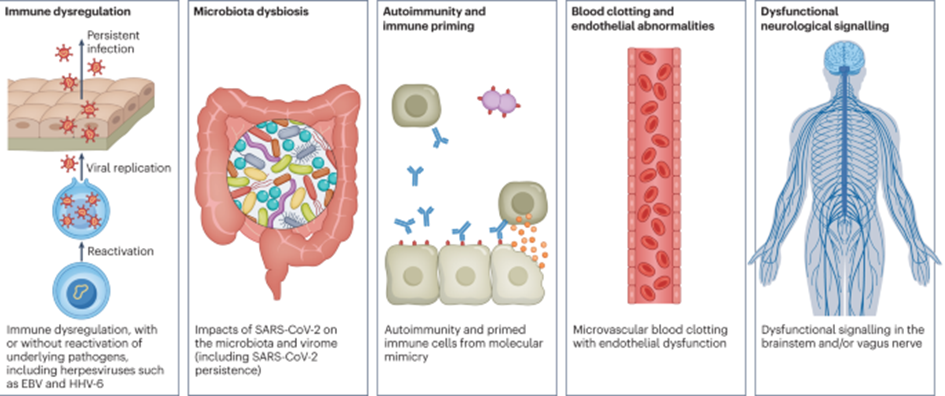

There are a couple of interesting theories on how this syndrome arises.

- ME/CFS and long COVID share many phenotypical similarities with burnout syndrome, which begs the question of whether these syndromes represent the nervous system going into a stubborn “safety mode” after a sufficiently large stressor. It seems that people who push themselves too much before recovery is complete are at a much-increased risk of developing long COVID. In fact, a neurologist in my area who specializes in long COVID suggests that a common pattern observed is that individuals who eventually suffer from long COVID tend to have exerted themselves excessively during their initial recovery phase. There is probably something to it as every single person with long COVID I know did some form of strenuous exercise before recovery was complete. Likewise, it seems that any “crash” gets the nervous system more deeply into the mechanism that causes long COVID, which potentially gives us a hint of how this syndrome arises in the first place.

- A heightened state of coagulability is frequently found in COVID patients and some researchers hypothesize that long-COVID is due to micro-clots obstructing proper tissue perfusion. Anecdotally, some people feel better on anticoagulants such as rivaroxaban. I find this hypothesis unlikely because of the strong symptomatic overlap between long-COVID and other postviral syndromes.

- There are hypotheses that post-viral syndromes are due to tissue destruction in the nervous system, leading to lasting and irreversible neuronal damage.

- In some patients, autoantibodies against certain receptors can be found. For example, in some studies, autoantibodies against muscarinic and beta-adrenergic receptors have been found. Support for this hypothesis comes from the fact that rituximab (a beta-cell depleting antibody) and hemofiltration help some patients – but unfortunately, only a small subset. Furthermore, there are published case series of complete recoveries after people were given the monoclonal antibody cocktail casirivimab/imdevimab – antibodies targeted at the spike protein.

- Some researchers hypothesize that Long-COVID is due to viral persistence. Anecdotally, some people feel somewhat better on Paxlovid (a combination of antivirals that prevents replication of the COVID-19 virus).

- Others hypothesize that Long-COVID is ultimately the same as ME/CFS and that it is caused by the reactivation of latent herpes viruses, particularly EBV. Some people with ME/CFS feel better on valacyclovir, an antiviral drug targeting herpes viruses.

While not mutually exclusive, (preliminary) evidence can be found for every single one of these hypotheses. However, none of these hypotheses can fully explain the pathogenesis of Long-COVID, which may ultimately come down to stubborn changes in CNS gene expression.

The only hypothesis we can probably exclude for sure is that Long-COVID has any causal relationship with the microbiome. The poor microbiome is nowadays unfairly blamed for all sorts of things.

My Long-COVID prevention protocol

Because of what long-COVID did to some people I know, I am keen on preventing Long-COVID from destroying my life as well. Next to the obvious things such as not exercising for a couple of days, during my recent COVID infection, I used an experimental combination of prescription drugs aimed at (potentially) reducing my risk of developing Long-COVID.

These drugs were used rather on the basis of first-principle reasoning than concrete scientific evidence, which at this point is not available.

Paxlovid

I took Paxlovid as soon as I noticed the infection. Other than a disgusting taste on my tongue that lasted all day, I already felt much better the next day. I continued taking it for the full five days.

Paxlovid is a combination of two antivirals developed by Pfizer. Nirmatrelvir inhibits a protease of SARS-COV2 whereas ritonavir inhibits CYP3A4, an enzyme that metabolizes nirmatrelvir. Long-COVID seems to be associated with disease severity. Paxlovid slashes viral load by up to ten times and reduces disease severity. While the data on Paxlovid and Long-COVID is conflicting, to me it seems that taking it has fewer risks than not taking it.

Valacyclovir

On the first evening of noticing symptoms, I took 2g of valacyclovir and then 500mg of valacyclovir twice per day for the next five days.

Valacyclovir is a prodrug of acyclovir, which inhibits viral thymidine kinase, an enzyme crucial to herpes virus replication. Long-COVID is associated with the reactivation of latent herpes viruses, particularly EBV. EBV is the virus that most frequently causes ME/CFS, which is probably pathogenetically similar if not identical to Long-COVID.

Valacyclovir is quite safe and there are no risks I can think of.

Rapamycin

I also took 5mg of everolimus as soon as I noticed the infection. Everolimus is a modified version of rapamycin. The major difference is that everolimus is a little more capable of entering the brain.

Everolimus is a mTOR inhibitor. mTOR activation is important for clonal expansion of lymphocytes, among many other things. Given that the damage from COVID (as well as disease severity) stems more from immune system overactivation than the virus itself, mTOR inhibitors have been suggested as a potentially disease-modifying treatment.

There is unpublished data by Matt Kaeberlein (a longevity researcher) that people who took rapamycin for longevity purposes during their active COVID infection had a reduced risk of developing Long COVID.

Of note, the ritonavir in Paxlovid also inhibits everolimus breakdown as it inhibits CYP3A4, the enzyme that also metabolizes everolimus.

Ketamine

On day six after my infection, I took 30mg of ketamine (subcutaneous injection).

Ketamine is an NMDA antagonist, which boosts neuroplasticity for 1-2 weeks after administration. I discuss the mechanism of action of ketamine in much more detail here.

If Long-COVID is indeed due to the nervous system entering “safety mode”, then artificially boosting neurogenesis shortly after the infection seems to be a plausible way to combat the nervous system from entering “burnout mode”.

Furthermore, after a viral illness “sickness behavior” usually persists for a couple of days, probably due to the cytokine-induced changes in monoamine signaling and neuroplasticity, both of which ketamine targets. Therefore, ketamine can at the very least help symptomatically by counteracting the postviral fatigue.

One friend has used ketamine three weeks after battling COVID symptoms. Starting 24 hours after administration, his brain fog cleared and his energy levels returned to normal, presumably because the effects of persisting neuroinflammation had been reversed.

How did it go?

I had a very mild course. I tested negative within 72 hours of developing symptoms and I was back to normal within 5 days. I had no lasting effect whatsoever. Whether any of my interventions helped, I do not know. 1 week later I was back to heavy exercise. At least my interventions did no obvious harm.

I plan on following this protocol every time I get COVID even though the risk of developing Long-COVID decreases with subsequent infections.

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

Interventions that may help with Long-COVID

Because of my friend’s condition, I was incentivized to do some research on what may help. Disclaimer: I am not an expert.

- Patience & pacing can go a long way. Things often get better on their own – though sometimes it takes a long time. Anecdotally, things seem to get better faster if people pace themselves, meaning they avoid any exertion whatsoever. Also anecdotally, people who do not pace themselves are made worse, sometimes permanently, by the ensuing “crashes” (post-exertional malaise). In this regard, obviously, “graded exercise therapy”, as it is often employed by ignorant doctors for CFS and related conditions, has destroyed many lives.

- NSAIDs, such as dexibuprofen, help reduce sickness behavior. A friend with Long-COVID takes 400mg twice daily and feels subjectively better on it than off it.

- Ketamine administration can temporarily (1-2 weeks) counteract the neuroinflammation-induced drop in neuroplasticity, which is associated with tiredness, among other things. Would be a cool research study to give people ketamine shortly after COVID to see whether the Long-COVID rates are any different. If Long-COVID is “the brain going into safety mode” than there might very well be an effect.

- Low-dose naltrexone seems to help some people. Naltrexone is a mu-opioid receptor antagonist, which next to blocking “pleasure” pathways also modulates parts of the hypothalamus as well as lymphocytes. s.

- mTOR inhibitors such as rapamycin or everolimus because of their ability to modulate the immune system, boost mitochondrial oxidation, and reduce neuroinflammation.

- Some people report benefits from taking minocycline, which through a poorly understood mechanism inhibits microglia (macrophages that are resident in the central nervous system).

- Some people report a decent improvement on a ketogenic diet, perhaps due to an anti-inflammatory effect or perhaps due to (potential) induction of autophagy. Two friends of mine on a ketogenic diet use low doses of empagliflozin (a SGLT2 inhibitor) to reach stronger ketosis (while also being able to eat more carbohydrates (Caution: if not done correctly, there is a risk of developing ketoacidosis on this combination).

- Anecdotally, periodic fasting to activate autophagy as well as to suppress the immune system leads to big improvements for some (e.g., a 72h fast every week or every other week).

- Some people report very small improvements from n-acetyl cysteine (NAC), alpha-lipoic acid (ALA), and coenzyme Q10. However, these supplements barely move the needle and the placebo effect is probably stronger than their benefit. These supplements are discussed in more detail here.

- Last in line is rituximab, a CD20-targeting antibody that depletes B-lymphocytes. As discussed above, it is hypothesized that, in some people, symptoms may be due to cross-reacting antibodies.

- Related to rituximab, it may be the case that, in some people, there is something in the blood plasma (perhaps autoantibodies, perhaps something else) that is co-responsible for causing some of the symptoms. Anecdotally, removing that (whatever “that” is) via plasmapheresis helps some. In fact, in Germany, some businesses are being built around this.

However, ultimately how exactly viral infections bring about their symptoms is poorly understood but it may ultimately have to do with neuroinflammation and stubborn gene expression changes in the central nervous system, for which currently no proper treatments are available – and probably will not be available anytime soon, regardless of what drugs pharmaceutical firms are trying to repurpose. There likely will not be an effective Long-COVID treatment soon but I could be wrong. So the best is probably a combination of luck and preventative measures, which, for me, include a couple of pharmaceutical drugs.

Sources & further information

- Scientific article: Treatment of Long-Haul COVID Patients With Off-Label Acyclovir

- Scientific article: The potential of rapalogs to enhance resilience against SARS-CoV-2 infection and reduce the severity of COVID-19

- Scientific opinion article: Ketamine in COVID‐19 patients: Thinking out of the box