I know a couple of people, myself included, who once claimed that intermittent fasting (16/8 to 20/4) has changed their lives.

After the initial uncomfortable adaptation period was over, I thought I had stumbled upon the holy grail. I loved how energetic I felt. Great energy, mood, sleep, fat loss, cognitive alertness. Every day I saved a lot of time and had a feeling of pride and accomplishment.

However, over the course of about half a year, I started to feel much worse.

I was always tired, cold, got very sleepy at night, had dry skin, a low sex drive, and pathetic energy levels. This “crash” was presumably brought about, at least in part, by drops in leptin levels, sex hormones, thyroid hormones, and cortisol. Conversely, the initial honeymoon phase was likely at least in part mediated by cortisol having been through the roof. These hormones are discussed in more detail here.

Furthermore, even though I intended to use intermittent fasting in part to free myself of thoughts about food, I was thinking about food much more than before. In the back of my mind, I was constantly looking forward to eating and I scheduled my day and life in a way that would suit my IF protocol.

In terms of personality, I became more rigid and neurotic.

Two major factors that could have negatively influenced my results were a presumably insufficient caloric intake and a lower-than-optimal body fat percentage. Might have been a different story if I had watched these two more closely. Nonetheless, intermittent fasting (as well as a ketogenic diet) decreases AUC levels of insulin and leptin more than an isocaloric “normal” diet.

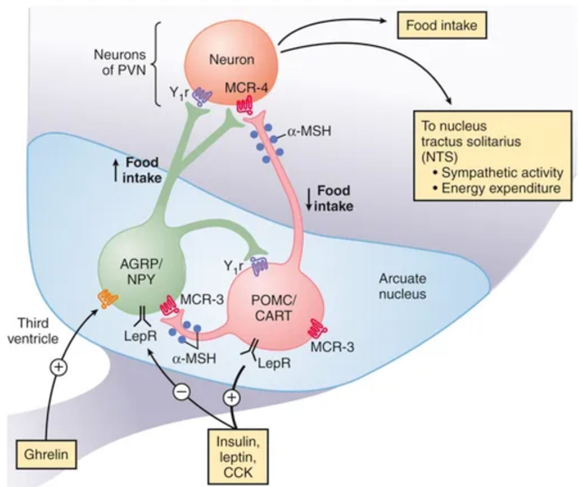

The decrease in insulin & leptin signaling results in the downregulation (suppression of activity) of a group of hypothalamic neurons (so-called POMC neurons) that are responsible for signaling to the brain that the organism has sufficient energy availability. At the same time, there is an upregulation of a second group of neurons (so-called AgRP-neurons) that are important for mediating the effects of energy deprivation.

These neurons are central to neuroendocrine and autonomic control, and whenever their activity is turned upside down (decrease in POMC-neuron activity; increase in AgRP-neuron activity), a lot of bodily systems are gradually shut down and people start to feel cold, hungry, weak, and are preoccupied with thoughts about food.

The downregulation in POMC-neurons is part of the reason why people have a challenging time keeping off weight after they have lost it. The fact that GLP-1 agonists like semaglutide activate this group of neurons is probably one of the primary reasons why GLP-1 agonists are such amazing weight-loss drugs (and in my opinion, perhaps even healthier and more sustainable than losing weight via the natural route).

People with good metabolic health (who already have low baseline insulin levels), and people with little body fat (who already have low baseline leptin levels), are obviously much more sensitive to a decrease in POMC-neuron activity. Therefore, intermittent fasting works quite well in people who are overweight and insulin-resistant but often does more harm than good in people who are lean and insulin-sensitive.

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

Upsides & downsides of intermittent fasting

During intermittent fasting, insulin is kept low for large parts of the day. During this time, cells are “taught” to use fatty acids for energy. Consequently, metabolism becomes more fat-adapted, and the subsequent shift from using glucose for fuel to using fatty acids for fuel helps with more stable energy levels, weight loss, and mental clarity, in part because a fat-adapted metabolism hardly ever runs out of available fuel because stored body fat is readily accessible.

On the metabolic side, keeping insulin levels low for most of the day promotes metabolic flexibility, counters hyperinsulinemia, and reduces insulin resistance. The improvement in insulin sensitivity helps with metabolic health.

Another major benefit of intermittent fasting is the slight elevation of plasma ketone bodies. Ketone bodies facilitate mitochondrial respiration, especially in the brain, which relies (almost) entirely on aerobic metabolism. This may in part explain some aspects of the cognitive alertness associated with fasting and a ketogenic diet, though the rise in cortisol levels, orexin levels, and adrenaline may also be part of the explanation.

This increase in mental clarity and alertness was one of the main aspects that I loved about intermittent fasting, though I only had it for a couple of months at best.

As mentioned above, for me, intermittent fasting had several adverse effects on endocrine systems (and likely also neurotransmitter setpoints). Down the line, I crashed severely, presumably because my hormones did so. Prolonged caloric restriction, intermittent fasting, or a ketogenic diet can all lead to hormone imbalances that may be hard to reverse – again, lean and insulin-sensitive individuals with low plasma leptin levels are more affected than individuals who carry a decent amount of body fat.

It seems that, for some people, intermittent fasting is great for mental health, particularly if said people are metabolically unhealthy in the first place. For others, not so much. As levels of leptin, thyroid hormones, and sex hormones decline, levels of serotonin decline as well (among other things). The accompanying mental rigidity, neuroticism, and obsessiveness may make it hard to stop, sometimes leading to a vicious cycle.

In my opinion, insulin-resistant individuals are far more likely to get benefits out of intermittent fasting and are much less likely to be harmed by it. If people have a lot of body fat (and are consequently more likely to be somewhat insulin resistant), I think intermittent fasting (or a ketogenic diet) is great for a variety of reasons, including better body composition, blood sugar levels, lipid profile, and blood pressure.

However, if males are already below about 15% body fat and especially if they are physically active, intermittent fasting may have more downsides than upsides – especially in the long run.

- Firstly, intermittent fasting may adversely affect multiple hormone levels (thyroid hormones, sex hormones, cortisol, leptin).

- Secondly, intermittent fasting may make people neurotic about food, and this, coupled with an increase in neuroticism that often accompanies fasting, can be a gateway drug into disordered eating, which can be mentally and physically brutal to recover from.

- Thirdly, for some people, intermittent fasting may eventually cause erratic blood sugar patterns, probably due to hormonal issues.

For some reason, females do not seem to do well on it, particularly if they are lean. At least that was the experience of some of my female friends. Even if caloric intake remained unchanged, some of them have lost their periods. Interestingly, not even that served as a sufficient warning sign, and some of them continued despite this.

Most eventually stopped, but one female friend gained weight like crazy, pointing to a potential (hypothalamic?) “reprogramming” of energy homeostasis, which lingered on for a long time. (I discuss this in more detail here: Weight Loss Is Not About “Calories In” Vs. “Calories Out”)

In sum, for some people, intermittent fasting can be a game changer for a variety of reasons. However, a non-minor percentage of people may eventually “burn out”, particularly if they chronically undereat, lose too much body fat, or have a fragile endocrine system.

Related articles

Sources & further information

- Podcast: Andrew Huberman – Effects of Fasting & Time Restricted Eating on Fat Loss & Health

- Scientific study: Potential Benefits and Harms of Intermittent Energy Restriction and Intermittent Fasting Amongst Obese, Overweight and Normal Weight Subjects—A Narrative Review of Human and Animal Evidence

- Scientific study: Intermittent fasting: Describing engagement and associations with eating disorder behaviors and psychopathology among Canadian adolescents and young adults

Disclaimer

The content available on this website is based on the author’s individual research, opinions, and personal experiences. It is intended solely for informational and entertainment purposes and does not constitute medical advice. The author does not endorse the use of supplements, pharmaceutical drugs, or hormones without the direct oversight of a qualified physician. People should never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something they have read on the internet.