Interestingly, most doctors do not know much about the microbiome, and I rarely hear anyone ever talking about it. However, for many laypeople microbiome-mania seems to have taken on religious qualities fuelled by populist books, press articles, and questionable podcast hosts. Given this dynamic, a more fitting title for this article might be: “The Most Overrated Field in the Public’s Perception of Medicine.”

What is a healthy microbiome?

The current state of microbiome research is quite crappy and there are a lot of gut-wrenching questions about causality. The billions of dollars put into this field have given us a lot of “it depends”. Among the major findings were that “microbial diversity is good” and “certain species of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria are good”.

Conversely, dysbiosis (a microbiome imbalance) is often characterized by decreased bacterial diversity. Some hypothesize that increased species richness prevents a single species from turning pathogenic via quorum sensing (a fancy word for intercellular communication between bacteria), which may change bacterial gene expression and behavior from “just passively hanging out” to becoming more aggressive.

In states of dysbiosis, there may also be a flourishing of “bad” bacteria (though nobody really knows who the bad guys really are and whether they are causal or coincidental).

To add further complexity, one person’s healthy gut microbiome may cause issues for someone else, as the same species of bacteria may behave quite differently in different environments.

How important is a healthy microbiome?

A couple of years ago (when I was on metformin), I got easily bloated and I often had digestive issues whenever I ate the “wrong” foods. Consequently, my vitality has taken a hit. Whenever I had gut issues going on, it was interesting to see how stimulants did not help at all with the lethargy or bad mood.

But whenever I took a low dose of loperamide (a gut-targeted opioid that calms down enteric hypermobility) this boosted my energy & mood within 30 minutes and for the whole day, I felt better. I blamed my bloating and indigestion on dysbiosis. Despite metformin being known to alter microbial composition, in retrospect, in my case, it likely had nothing to do with microbes that much.

In my opinion, the microbiome is one of the most overrated topics in medicine. Lots of relationships in all directions and lots of confounders, such as immune system specificities. But to me, in the end, it seems that much of the published research is just hot air.

There is some Mendelian randomization evidence (which I generally regard very highly) regarding some aspects of human health (e.g., the development of microbiome-related genes and Long-COVID), though a difficult third variable to tease out is individual immune system “specs”, such as individual propensities to generate certain subsets of lymphocytes or cytokine milieus (both of which indirectly affect microbial composition).

Microbiome research is a prime example of the intrinsic human need to find patterns and explanations (even if there are none). I would not be surprised if people started to make statistically significant associations between gut flora and the weather.

While I admit that I have not been very anal about inspecting the literally crappy field of microbiome research, my gut feeling is that most of the hype around it is bullshit, possibly only relevant to a single-digit percentage of people (which, for microbiome “activists”, may be hard to stomach). Said in other words, in my opinion, the majority of people (roughly 80-90%) who have an “alright-enough” microbiome will not be overly affected by it, while a small subset of patients will benefit a lot from microbiome-related interventions. I have no data to back this up and this is only a gut feeling.

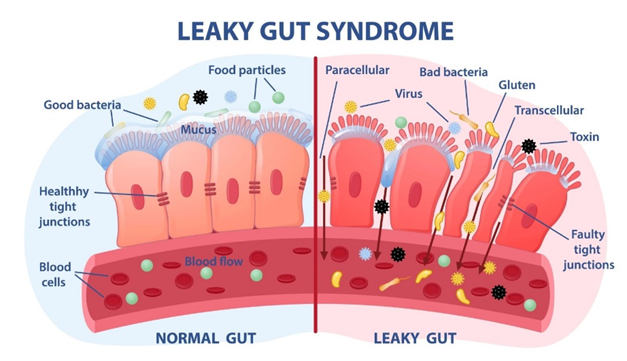

While I may be biased, I believe that the microbiome is far less important than what people make it out to be. Far more important are impaired ENS-CNS interactions, non-microbiome-related food insensitivities (e.g., gluten, dairy, eggs, lectins), allergies, immune dysregulation, increased intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”), psychogenic issues (e.g., anxiety), or dysregulation of gastrointestinal peptides and metabolic hormones, but this does not necessarily mean that there is primarily anything wrong with their gut flora even though statistically significant associations may tempt to believe otherwise.

H. pylori infection, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), and candida overgrowth may be an exception.

In all of these conditions an altered microbiota may be found but that tells us little about causality. Like with Alzheimer research, sure, there is some causality going from amyloid plaques and the disease but it is probably not the primary cause of the disease. In other words, the amyloid just adds fuel to the fire and removing it improves the condition a little bit (perhaps in the low digit percentage range).

There are a host of studies showing that certain conditions improve if the microbiome is altered. However, most inflammatory conditions also improve if you take out inflammation (even if the inflammation is not the root cause). The inflammation is a consequence of a root cause (e.g., tendon degradation) and adds fuel to the fire. If you then give anti-inflammatories, the condition gets a little better but the root cause is still there. I view the microbiome similarly.

The gut microbiome seems to be one of these things where the more someone hears and learns about it, the more likely someone is to fall prey to “microbiome tunnel vision”. It surely does not help that the lay public has been hyped up about a topic.

I am more than willing to change my current stance (which is that the gut microbiome is not a significant factor in around 80-90% of people who believe otherwise) as soon as practical and effective therapeutic interventions have been developed.

As far as I know, despite billions of dollars having been invested in microbiome research, very little to nothing practical came from it other than “Eat a varied diet. Eat whole foods. Cut out processed crap.”, which all improve many non-microbiome-related things as well.

“Leaky” gut?

I am not sure what to make of “leaky gut syndrome”. Two of my friends, both MDs, really believe in it. “Leaky gut” is characterized by increased translocation of LPS (a component of bacterial cell membranes) and an elevation of CRP, certain interleukins, and fibrinogen (all indicators of certain aspects of inflammation).

It is unsure whether microorganisms are to blame at all as altering them seems to make little difference in symptomatology. Tight junction modulators are promising though, for some reason, some failed to meet endpoints (e.g., larazotide).

How to promote a healthy microbiome?

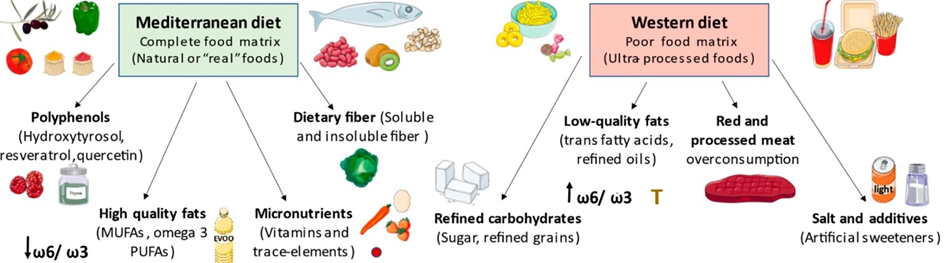

It turns out that my microbiome is mostly regulated by what I eat (who thought?): The amount of soluble and insoluble fiber (or lack thereof), prebiotics, and a variety of phytochemicals (e.g., polyphenols) all affect the quality of the “garden” I have growing inside me.

Indigenous tribes, who generally eat a diet rich in diverse kinds of fibers, seem to have “better” microbiomes. Conversely, a typical Western diet, which is usually low in “real” food, and high in artificial sweeteners, preservatives, pesticides, and trace amounts of antibiotics, seems to be linked to a “worse” microbiome, linked to more gut issues (e.g., indigestions, bloating, etc.) and unfavorable associations with pretty much any medical condition under the sun (e.g., depression, anxiety, cancer, etc.) – though obviously, there are many potentially confounding third variables.

Fortunately, it seems that diet can alter the microbiome in relatively short timescales.

In the past, as I still cared about the microbiome, I did a couple of things aiming to improve my microbiome:

- I avoided gut-irritating stuff such as carrageenan, NSAIDs, and alcohol. I also avoided eggs as I seem to react badly to them. Furthermore, I avoided probiotics as, all things considered, they seem to be a net harm for most people.

- I focused on a diet rich in whole foods and fiber.

- I supplemented with psyllium husk (a mostly insoluble fiber) to increase bulk, promote bowel movements, and “coat” my gut lining protecting it from mechanical irritation.

- I supplemented with low doses of inulin (a prebiotic soluble fiber) to help with increasing “good” gut bacteria (e.g., certain species of lactobacilli and bifidobacterial), to decrease intestinal permeability, and to promote the microbial secretion of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), the latter of which are linked to an improvement in intestinal barrier function (e.g., LPS translocation), metabolic health, and gastrointestinal immune function. Acacia fiber is basically “slow-release inulin” with reduced side effects (e.g., indigestion, bloating, flatulence) and supplementing with it was particularly helpful to adapt to inulin supplementation.

- I ate small amounts of fermented foods every day. My favorite was a couple of spoons of sauerkraut. A friend says that he reacts badly to fermented foods, because, according to him, he may get swamped with histamine, which may be able to cross the gastrointestinal barrier in individuals with increased gastrointestinal permeability (“leaky gut”).

- Twice, I tried to “reset” my gut flora by taking rifaximin, a gut-targeted antibiotic.

Interestingly, after quitting metformin, all my gut issues went away. I felt stupid about all of the things I read, did, and tried.

Off-topic: Will I be caries-free forever?

Some time ago, I (permanently) modified my oral microbiome.

A friend who visited from San Francisco smuggled something highly illegal into Europe – genetically modified bacteria. A couple of days later, a couple of friends and I were brushing these bacteria into every nook and cranny of our mouths for 10 minutes. Thereafter, we feasted on the most sugary junk we could find to feed our new co-inhabitants.

Streptococcus mutans is the bacterial strain single-handedly responsible for human caries.

BCS3-L1 is a genetically modified strain of Streptococcus mutans designed to combat dental caries. This strain was engineered by deleting the gene responsible for producing lactic acid (the acid component of which erodes enamel) and produces ethanol instead (in minute amounts). Furthermore, it was modified to produce the antibiotic mutacin, which gives it a competitive advantage over native S. mutans because it has been engineered to be mutacin-resistant itself.

There have been some human data for 30 years and nobody was reported to get caries after the first (and only) application. Furthermore, studies in laboratory and rodent models have shown that it is genetically stable, with no apparent side effects, and its ability to colonize effectively suggests long-term prevention after a single application. If things went as planned and my mouth is currently being colonized with it (it will probably take a couple of months for complete outcompetition of native S. mutans), I will never have caries again.

Sources & further info

- Scientific review: Help, hope and hype: ethical considerations of human microbiome research and applications

- Podcast: Peter Attia & Michael Gershon: The gut-brain connection

- Opinion article: Microbiome research: overhyped or the great hope?

Disclaimer

The content available on this website is based on the author’s individual research, opinions, and personal experiences. It is intended solely for informational and entertainment purposes and does not constitute medical advice. The author does not endorse the use of supplements, pharmaceutical drugs, or hormones without the direct oversight of a qualified physician. People should never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something they have read on the internet.