When it comes to diet, many people believe that they have it all figured out but everyone else got it all wrong. However, diet science is an absolute mess and everyone can “disprove” almost anything anyone else says by cherry-picking from the available literature.

It seems that a lot of people got stuck on “nutrition absolutes” and miss the “it depends” part. The “optimal” diet almost certainly differs depending on several factors, such as activity levels, metabolic health status, body fat percentage, hormones, and genetics.

For example, reducing carbohydrate consumption makes sense for an insulin-resistant, sedentary, and overweight individual whereas it might do more harm than good for someone who is highly insulin-sensitive, active, and lean.

In an ideal world, people would be able to do their own research, but unfortunately, some of the research done in medicine, and especially in nutrition medicine, is inherently flawed due to bad study design, bad data-gathering practices, bad semi-objective measurements, confounded observations, using statistics in ways that amount to lying, or financial incentives.

Furthermore, like research about what kind of psychotherapy is most effective, a lot of nutrition science seems to mostly corroborate the previously held “conclusion” of the authors.

Below is a list of things I found work for me, some of the things I did in the past, and some comments on a couple of things some of my friends are doing. As with everything else on this blog, most of this is n=1, so it is best to be taken with a grain of salt.

80/20 principle

In my early twenties, I tried to be a diet perfectionist, which caused a lot of unnecessary stress and took away from life enjoyment. I now try to adhere to a good diet about 80% of the time, and for the rest of the time, I care little. I believe that occasionally eating “crap” if I need or want to, is not that big of a deal if my staple foods (the foods I eat 80% of the time) are good.

Macronutrients

There are few more polarizing diet topics out there than whether carbs or fats are good or bad. As with so many other things, it depends.

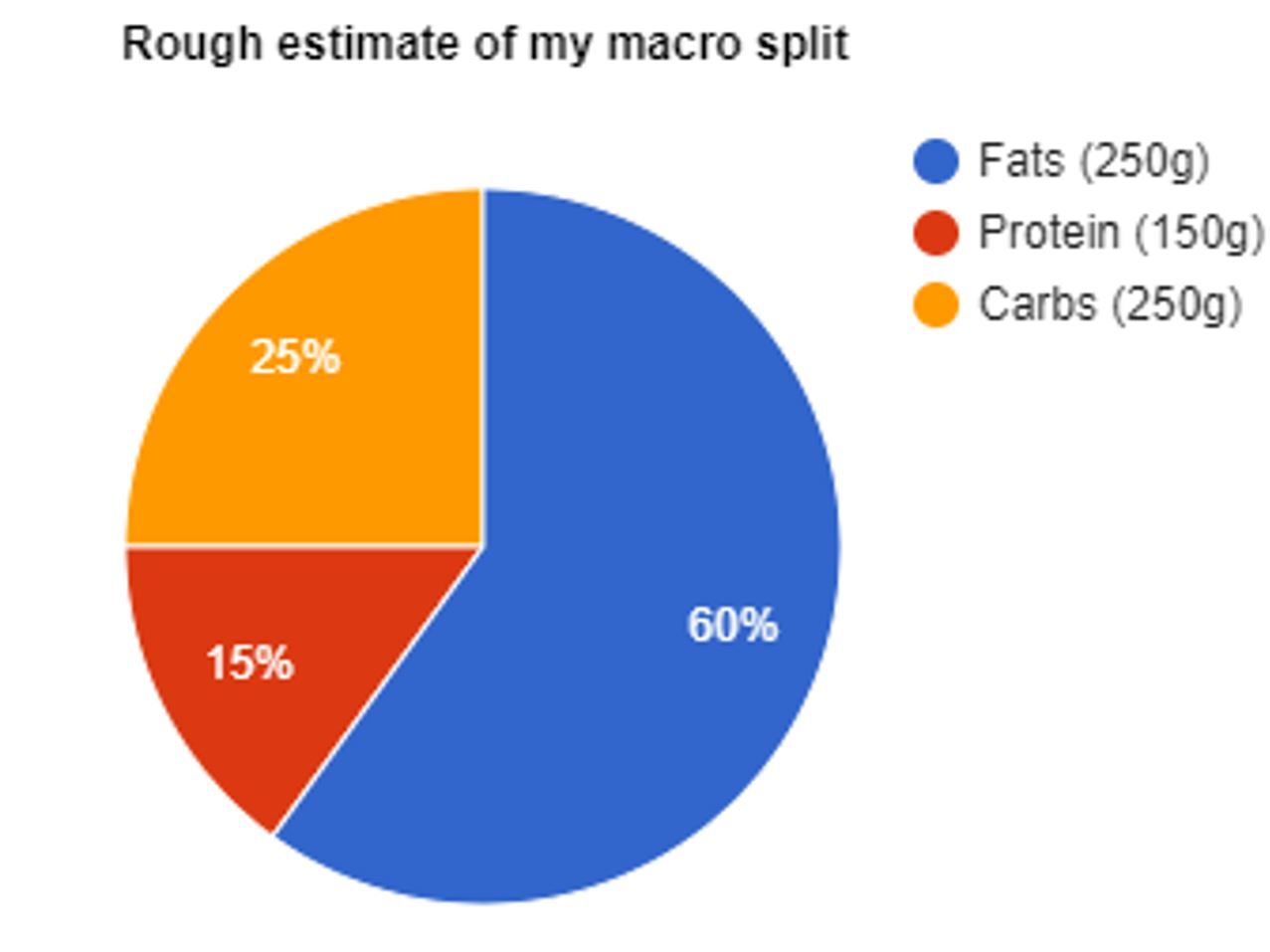

Under normal circumstances (about one hour of exercise per day; 10-11% body fat), my preferred macronutrient composition is about 250g carbs, 250g fats, and 150g protein, though I am quite lenient with switching up carbs and fats, depending on whether I eat by myself or with friends. I also make sure to consume enough fiber (I particularly like the beta-glucans found in oats).

Fats

My preferred fat choices are monounsaturated fats (“good” fats), which I prefer over saturated fats, which in turn I prefer over polyunsaturated fats (mostly vegetable oils other than olive oil). I also aim to get about 2g of EPA/DHA per day (discussed in more detail in my article on supplements).

I usually go through two liters of olive oil per week (about 300ml per day). Olive oil is extraordinarily rich in monounsaturated fats, and it seems that almost everyone does well on monounsaturated fats. Conversely, some people react badly to saturated fats (in terms of their lipid profile), and some people claim to react badly to polyunsaturated fats.

Carbohydrates

I titrate my carb intake to leanness and activity levels. Whenever I am very lean and/or highly active, reducing carbs is a bad idea. When I am less lean or less active, I try to reduce carbs and increase fats. However, I almost never reduce carb intake below 150g or so because I consistently feel and perform worse when I do.

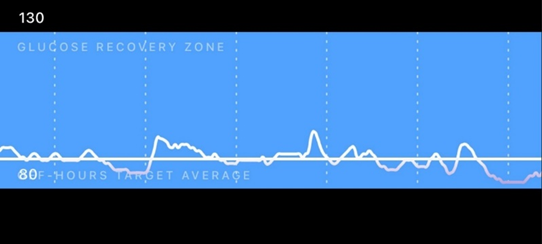

My preferred carb choices are slow-releasing complex carbohydrates, such as oats. Whenever I eat a lot of fast-spiking refined carbohydrates (“bad carbs”) my cognitive function & alertness decline for a couple of hours unless I have exercised beforehand (after a hard workout, a lot of the ingested glucose is partitioned to my glycogen-depleted liver and muscle tissue). Therefore, I try to eat “bad carbs” predominantly in the evening or after heavy exercise.

Because I am lean, active, and pharmacologically hack my metabolism, I am quite insulin-sensitive. Therefore, I can tolerate carbs very well and my body can dispose of them adequately by burning them or shuttling them into glycogen synthesis.

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

Conversely, if my glycogen stores were always tapped out (e.g., with a sedentary lifestyle), excess glucose is biochemically much harder to manage and comes with a host of unfavorable biochemical alterations.

When it comes to carbs, there is no “one size fits all”. An individual’s carbohydrate tolerance can vary quite a lot and depends on a number of genetic factors (e.g., variants in the PPAR-family of transcription factors), hormonal factors (e.g., IGF-1, thyroid hormones, sex hormones, AUC-levels of cortisol, leptin, adiponectin), insulin sensitivity, and activity levels.

Interestingly, pretty much all the high-energy people I know eat a diet rather high in carbs, including some fast-spiking carbs (“bad carbs”). I personally have also seen large benefits in terms of energy levels since increasing my carb intake. While I did have some temporary lethargy, it seems that in the long run, my baseline energy has increased.

Nonetheless, I believe that a low-carb, high-fat diet is great for people who are mostly sedentary, overweight, or insulin-resistant. I will discuss my thoughts on ketogenic diets in more detail shortly.

A couple of years ago, I was occasionally using the drug acarbose, a glucosidase inhibitor, which “converts” fast-spiking (“bad”) carbohydrates into slow-release (“good”) carbohydrates. I did this to mitigate the negative effects of high-glycemic meals (e.g., at social gatherings when avoiding shitty food is a nuisance). Unfortunately, even microdoses consistently spiked my liver enzymes.

There seems to be something harmful about large glucose spikes and they seem to be associated with all kinds of bad long-term consequences, including a reduction in lifespan. Some researchers speculate that large glucose spikes trigger something “bad” within the hypothalamus. Of note, the lifespan benefits of canagliflozin (an SGLT-2 inhibitor) or acarbose (a glucosidase inhibitor) likely come down to, at least in part, a blunting of peak glucose levels. I discuss my experience with metabolic drugs in more detail here: Metabolic Drugs.

Processed foods

I avoid overly processed foods when I am eating by myself, but I do not care about it too much in a social setting (80/20 rule).

Processed foods have several things wrong with them: A lot of sugar and salt, a lack of fiber, excessive amounts of omega-6 fatty acids, a lot of additives, and usually a high caloric density.

Sugar

Like processed foods, I avoid sugar when I am eating by myself (but not socially) because I find sweetness per se to be addictive. Fructose is not only addictive and hunger-dysregulating, but the specific metabolism of fructose has a variety of detrimental effects on metabolic health, which I care about. I discuss sugar, fructose metabolism, and artificial sweeteners in more detail here.

Variety

I do not eat a varied diet and I also do not think that variety is essential. In my opinion “Eat a varied diet.” is only useful advice if my intake of micronutrients (vitamins & minerals) were poor. After I have found what works for me, I prefer eating the same things over and over again. Every other mammal out there does this.

The diet in “blue zones”, areas with the longest human life expectancy on Earth, is rarely varied. Yet, on average, blue-zone people live to a comparatively very old age and are in comparatively excellent health.

Caloric intake

It is not just about what I eat but also about how much. In my opinion, the total amount of calories is one of the most important factors when it comes to diet. From an energetic point of view, everything I eat becomes electron-donors and, according to the deepest principles of physics, my body can just give out what I put in – at least in the long run.

In the past, my obsession with “fitness” caused me to undereat for a lengthy period of time. For years, I was trying to survive on 2200-2400 kcal/d because online calculators aimed at figuring out my TDEE “determined” so. Furthermore, I was also reckless with intermittent fasting & keto-style diets (more on that shortly).

After gradually increasing my caloric intake by about 1000 kcal/d, I started to feel much more alive, and my energy levels and mood increased significantly. Increasing my caloric intake was one of the best things I ever did for my energy levels.

Interestingly, despite eating vastly more, my body fat percentage remained about the same. I guess I fall into the high non-exercise-induced-thermogenesis (NEAT) category and if I eat more a number of hormones increase and I subconsciously raise my activity levels.

I find that the caloric intake I feel and function best at is the highest tolerated number of calories that does not result in fat gain. For me, that is around 3500-3800 kcal/d. Whenever I eat less than 3000kcal for a couple of days, my vitality decreases considerably, especially if I also do heavy exercise.

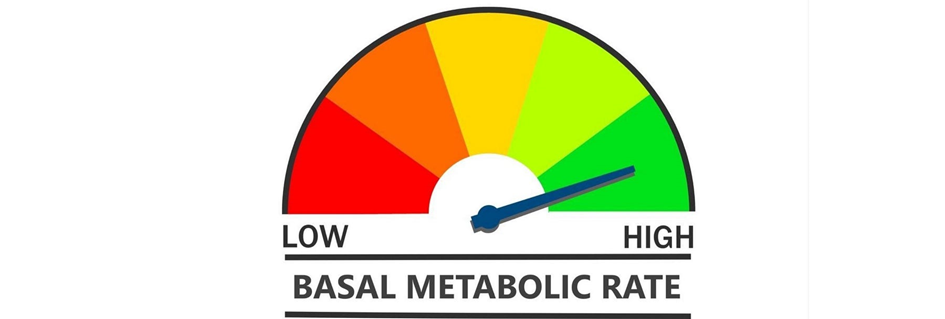

By far the greatest determinant of how much I burn is my basal metabolic rate (BMR). My BMR primarily depends on three things:

- Speed of metabolism: The speed of metabolism is mostly determined by a variety of hormones, in particular thyroid hormones. Because I supplement with thyroid hormones, my BMR is a little higher than it would be otherwise.

- Muscle mass: This is the speed of metabolism applied to muscle tissue. I have a decent amount of muscle tissue, which burns calories even if I just sit around, and much more if I exercise.

- Sympathetic nervous system activity: It is thought that differences in sympathetic nervous system activity are the biggest factor explaining different BMRs of people with the same weight and body composition. How strongly active a sympathetic nervous system is depends on genetics, hormones, stress level, stimulants (of which I mostly use nicotine), and ambient temperature. I guesstimate that my consumption of nicotine gum increases my BMR by about 150-250 kcal per day. I also prefer to work in a cold environment because I feel that it increases my alertness and cognition. Because of these factors, my sympathetic nervous system activity is (presumably) fairly high and requires a lot of energy to maintain.

I discuss why a “calorie” is not a “calorie” in more detail here: Why Weight Loss is not About “Calories In vs. Calories Out”

Body fat

I care about being lean because it makes me look much better overall. For me, the difference between being 10% body fat and 15% body fat is night and day, particularly my face. Furthermore, being lean is one o the best things I can do for my metabolic health and insulin sensitivity.

I usually hover in the 10-12% range (as measured by DEXA scans I do about twice per year). In the pictures below I was at 10.6% body fat.

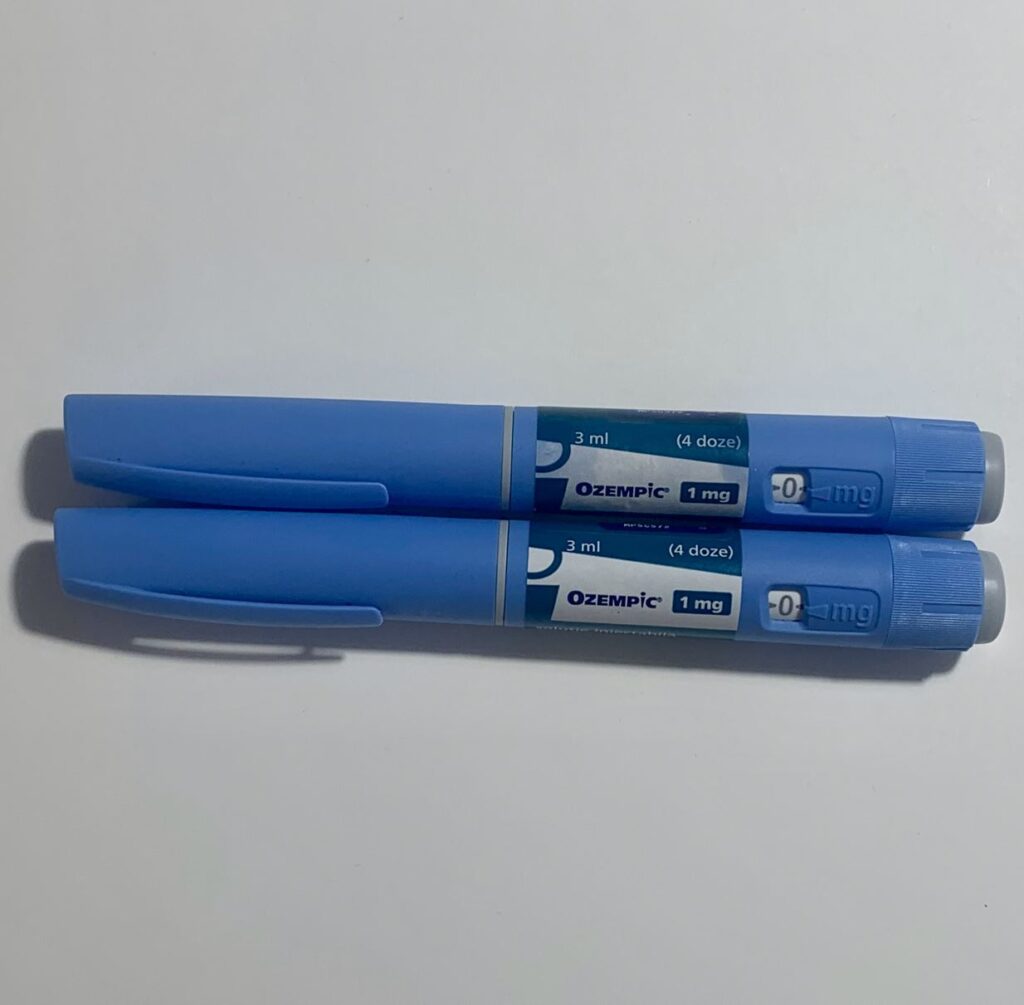

Hopping on semaglutide allowed me to keep my body fat fairly low without almost any effort. In fact, I need to watch my calories closely so that I do not undereat. Whenever my body fat gets below 10%, I feel and function progressively worse, regardless of whether I am on semaglutide or not. My energy, mood, libido, concentration, and vitality take a severe hit. I discuss this in more detail in the section on leptin.

It seems that most males feel and function best somewhere between 13-18% body fat, whereas most females feel and function best between 21-26%, though there is some interindividual variation.

Body fat is highly sensitive to genetics. There are a ton of people who do “everything right” but their body fat will hardly go below 15%. Conversely, there are others who can eat whatever they want and they are constantly under 10%. Next to hormonal factors, there are many other genetic factors, such as the amount of uncoupling protein (UCP1) expression.

Water intake

Even mild dehydration affects my energy, mood, attention, and cognition. I know that I am dehydrated when my voice starts to sound weaker and breathy.

I try to drink about 3l of water per day but not more than that (other than on days with excessive exercise or heat). Drinking too much water can wash out the medullary concentration gradient in the kidneys necessary for concentrating urine, which promotes polydipsia and electrolyte disturbances.

I do not use water filters because the water in my city & house is naturally of decent quality.

Food intolerances

Figuring out whether I have an intolerance to a certain food is worth a lot.

- Eggs: I react badly to eggs but only if I eat them often. After two weeks or so of regularly eating eggs, I get tired and sluggish after eating them. This may be due to an immunological reaction against certain protein epitopes found in egg white.

- Dairy: One of my friends reacts badly to dairy, and after consuming it he feels lethargic for a couple of hours. This could be due to an immunological sensitivity to the alpha-s2-casein fraction, which actually seems to be quite common. I share my thoughts on dairy in more detail here.

- Nuts: To prevent immune sensitization, I make sure to rotate different nuts.

- Grains: My aunt recently asked me about my thoughts on grains. Most people who claim to be immunologically intolerant to grains can likely tolerate grains just fine. The whole “gluten-free” thing is, in my opinion, mostly a marketing scam. Though I am open to updating my current stance.

I have researched insensitivity tests (somewhat) thoroughly and it seems that apart from lactose intolerance and celiac disease (gluten), there is no accurate, reliable, and validated test to identify food intolerances. Even tests such as Cyrex only identify immunological reactions but are blind to adverse food reactions caused by microbial or digestive issues, which makes them somewhat worthless.

The best diagnostic tool to find out whether one reacts badly to a certain food is likely a cumbersome exclusion diet.

Superfoods

Over the years, I have tested many and none had a significant impact besides stimulating the economy. So far, the only superfood I have found is olive oil, which I consume a lot (normally about 200-300ml per day).

Thoughts on veganism

One of my friends has been vegan for about six years and has great energy, mood, and health. Another of my friends would like to be vegan for ethical reasons, but every time he tried to go vegan he became depressed a couple of months after transitioning to a vegan diet. He believes that this is due to a deficiency of something that cannot be had through multivitamin supplementation.

Some people seem to tolerate a vegan diet fairly well, whereas others get physical and mental health issues.

Subscribe to the Desmolysium newsletter and get access to three exclusive articles!

The vegan diet contains only meager quantities of a variety of nutrients, including creatine, carnosine, choline, carnitine, coenzyme Q10, taurine, zinc, iron, and vitamin B12. Studies consistently show that vegans have reduced blood levels of many of these. I discuss these nutrients in more detail in the next section on nutrients & supplements.

Some of these are synthesized endogenously to some extent, but the individual capability to do so varies. Speculatively, this is one reason some people fare badly on a vegan diet. Overall, I believe a vegan diet is great for ethical reasons, but not optimal for health reasons (unless one is willing to take a shitload of supplements – far more than just vitamin B12 and iron).

There are some (epidemiological) indicators that a plant-based diet may be associated with longevity. Is this purely due to the healthy user bias? Is this because vegans unconsciously restrict leucine and methionine, two amino acids that activate the mTOR pathway? Is this due to nitrates, vitamins, or antioxidants found in plants? We still do not know though all of these may play a role.

Intermittent fasting

I have experimented with many forms of intermittent fasting. Intermittent fasting is the easiest, the most enjoyable, and the most effective approach to give me dietary freedom, effortlessly low body fat, mental clarity, and simply have me perform at my best. Or at least once I thought so. Well, all it did was lead to disordered eating and damage my body and mind like few other things ever have.

Reportedly, for some individuals intermittent fasting can lead to feeling awesome, sometimes even for prolonged periods of time. For others, not so much. I was in the latter group. We are all different.

I discuss my experience with intermittent fasting in more detail here.

Ketogenic diet

A couple of years ago, I was on variations of a keto-style diet for a little over a year. This wasn’t overly well received by my friends, family, and girlfriend due to the difficulties in eating together. However, my sleep requirements went down by over an hour, which was worth a lot to me. My experience was okay, though, after a couple of months, I started to burn out as I did with intermittent fasting.

On a ketogenic diet, insulin levels are kept extremely low, which results in a rise in blood ketone levels, weight loss, a diminishment of appetite and cravings, stable energy levels, reduced sleep needs, upregulation of autophagy, and a decrease in inflammation. Together, these upsides make ketogenic diets quite useful in the right context.

Dr. Peter Attia claims that a ketogenic diet works especially well for three groups of people:

- ultra-endurance athletes

- type II diabetics

- individuals that cannot afford ups and downs in energy levels (e.g., day traders)

However, applied in the wrong context, a ketogenic diet can also be quite harmful. I share my experience and thoughts on a ketogenic diet in more detail here. I also discuss two drugs that can make adhering to a ketogenic diet easier.

Multi-day fasting

I have done about fifty or so 36–48-hour fasts, about ten or so 5-day fasting-mimicking fasts (eating about 500kcal per day in the form of vegetables and unsweetened peanut butter), and one 9-day water fast.

During my fasts, I supplemented with extended-release potassium (400mg four times per day), salt (3-5g per day), magnesium (600mg per day), and calcium (200mg per day). Interestingly, whenever I consumed a lot of calorie-free sweeteners (mostly in the form of gum and diet Coke), I was kicked out of ketosis and “felt like shit”.

Multi-day fasting has a lot of upsides, and on paper, it is protective against a host of chronic diseases. Multi-day fasts are thought to promote metabolic flexibility, help with metabolic health (insulin resistance, lipid levels, blood pressure, etc.), ramp up autophagy and potentially induce apoptosis of senescent cells and a proliferation of stem cells.

However, for me, it has done more harm than good. For example, it caused a loss of muscle mass, and it screwed up my hormones and metabolism. The major benefits I noticed were a feeling of accomplishment and a build-up of self-discipline. During my fasts, I usually became a productive demon completing about two weeks’ worth of tasks in only five days.

In sum and in my opinion, fasting kills vitality in the long run and is only net beneficial if one is metabolically unhealthy or overweight. I do not plan on returning to multi-day fasting during the next couple of years, potentially forever.

I share my experience with multi-day fasts in more detail here.

Carnivore diet

Two friends of mine claimed that the carnivore diet helped them with self-diagnosed autoimmune problems. It perhaps did so by removing food allergens, reducing insulin and IGF-1 levels (and therefore reducing mTOR-pathway-associated inflammation), or by bringing about changes in the microbiome due to the starvation of the microbiota in the large intestine.

I like what Dr. Peter Attia has to say about it: “One has to be careful because the cheerleaders are the ones, you’re hearing the most. You don’t get to see what the graveyard looks like for all of the people who tried carnivore and didn’t have favorable results.”

Both of my friends have been quite vocal about the carnivore diet as they were starting out, wanting everybody else to try it. Both have quit it quietly.

Thoughts on the microbiome

In my opinion, the gut microbiome is far less important than what it is currently made out to be. I discuss my thoughts on the current microbiome mania here.

Thoughts on other diet-related topics

Because this article is already awfully long, I share my thoughts on a number of other dietary topics including protein, meats, salt, fiber, dairy, sugar, legumes & grains, and artificial sweeteners here.

My diet in more detail

In the past, I have been experimenting with intermittent fasting, low-carb, paleo, and keto-style diets for multiple years. Nothing else I have done, and I have done a lot, has worsened my vitality as much. It has also wrecked my metabolism, hormonal health, and appetite regulation. The damage took a long time, and pharmaceutical intervention, to recover from.

Hopping on the GLP-1 agonist semaglutide (discussed here) showed me how much of my day was taken up by thinking about food. Since considerably increasing my caloric intake, I feel much more energetic and alive. After 3 years on the drug, I am currently off it because I want to gain body mass.

I now follow three loosely held rules to which I aim to adhere about 80% of the time:

- Cutting out most of the processed food and sugar (80/20 principle)

- Eating the highest possible number of calories that does not result in fat gain (which was much higher than what online calculators led me to believe)

- Making sure that my carbohydrate intake is appropriate for my leanness and activity levels

The consistent program that I follow is better than the perfect program that I quit. I believe that if I follow these points, I get a major share of what is maximally attainable through dietary intervention.

Many people treat diet like religion, but, in my opinion, diet is actually not that important if a couple of principles and rules are adhered to. Going from a shitty nutrition to an okay diet has huge benefits but going from an okay to “perfect” diet (whatever that means) is probably somewhat of a waste of time and energy.

I believe that if I am already on a reasonable diet, dietary intervention is a low-leverage lever to pull, especially compared to sleep and exercise.

On workdays, about 60-80% of my calories consist of Huel shakes. To each shake, I add about 70ml of olive oil to increase fat content and one scoop of whey protein to increase protein content, making each shake about 1200 kcal (about 100g fats, 45g carbs, 55g protein). I am usually drinking 1-2 of these shakes plus a 1-2 normal meals and perhaps a snack.

(Update: I switched out the Huel shakes for Kefir yogurt drinks (500ml) – mostly because the kefir bottles are smaller than the Huel shakes and can more easily fit into my backpack. Furthermore, kefir drinks only contain half the volume compared to Huel, cutting down on the number of times I need to go to the toilet. I also love the taste (though few people I have given them to try do). To each I add 70ml of olive oil and one scoop of whey, making each drink roughly 850 calories. On work days I usually drink 2-3 (mostly 3) per day. I personally like dairy products and react well to them. While a high dairy intake is probably not “optimal” for many reasons, I do not really care because I like it and I love the convenience associated with it. Furthermore, dairy elevates IGF-1 levels. Compared to most people in the health-sphere (“dairy/IGF-1 causes cancer”), I do think that there are more upsides than downsides with slightly higher IGF-1 levels. Ever since embarking on a high-dairy diet, my ApoB levels rose from the 3rd to the 6th percentile – though, for some people dairy might be harsher on their lipid profile due to polymorphisms in the PPAR-transcription factor family.)

The biggest upside of a diet like this (i.e., getting over 50% of my calories from meal replacement drinks (first Huel, now Kefir) is the convenience – it takes me about one minute to prepare. It does not lead to a noticeable increase in blood glucose levels. I never need to worry about hitting my calories, good fats, and protein intake. Furthermore, I never have a post-meal energy slump, and it gives me stable energy for hours. The taste is okay.

While my diet is certainly far from “optimal”, I hit my calories, have okay-ish macros, and rarely eat junk – the most important points anyway.

On non-work days I am much more flexible and liberal with my diet. However, as said, I believe diet is not as important as it is usually made out to be (given that the diet is already okay-ish) and is overrated compared to sleep, metabolic health, exercise, or hormones.

How I Biohack My Vitality

This article is a subsection of How I Biohack My Vitality.

Related articles

Sources & further information

- Scientific literature: In my opinion, the scientific literature is unfortunately of little value when it comes to answering questions about diet as most of the available literature is based on epidemiology. Furthermore, there is presumably no other field in which scientific “evidence” contradicts itself so much.

- Scientific article: Mediterranean diet and health status: Active ingredients and pharmacological mechanisms

- Podcast: Peter Attia (The Drive): How Fructose Drives Metabolic Disease

Disclaimer

The content available on this website is based on the author’s individual research, opinions, and personal experiences. It is intended solely for informational and entertainment purposes and does not constitute medical advice. The author does not endorse the use of supplements, pharmaceutical drugs, or hormones without the direct oversight of a qualified physician. People should never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something they have read on the internet.